The earliest point in time I can remember hearing about Jack Kirby’s legacy and how the comics industry treats its creators didn’t come from the Marvel comics I’d save or trade for. It came in the first adult comic I ever read, Frank Miller’s Sin City: The Big Fat Kill #5. As a kid, I was much more interested in the nudity, blood, violence, language, and art. As an adult, and after putting a lot of thought into this subject over the past couple years, I can appreciate Miller stumping for Kirby a little better.

I didn’t see this anywhere online, and I’m pretty sure that you can’t actually buy this issue new any more, so here it is: “Keynote Speech By Frank Miller To Diamond Comic Distributors Retailers Seminar, June 12th, 1994”. I’ve pasted the images and OCR’d text below. If you’re gonna quote it, please check against the images. I used Adobe Acrobat’s OCR function to get this done, and may have missed an error or two.

I’ve gotten a lot of requests from readers who heard about what follows and would like to see it. The speech kicked up quite a ruckus- and inspired some wild exaggeration, and at least a few lies by people who didn’t like it. This transcript includes all of my many, many ad-libs and is only lightly edited to remove redundant phrases.

Allow me to set the stage. The hall was gigantic. Somewhere around 3,000 comic-book professionals were there, predominantly retailers, but including representatives of nearly every major publisher, as well as dozens of writers and artists. Following a very generous introduction by Diamond boss Steve Geppi, I stepped up to the podium, stomach lodged squarely in throat…

Let me get started by asking you all to join me in honoring two good men we recently lost. I’m corny enough to ask you to stand up for this part. A round of applause, please, for as dear a friend as comics ever had: Mr. Don Thompson. And another round — let’s make this an even bigger one; I want the walls to shake this time — for the greatest artist in the history of comics, Mr. Jack Kirby.

Well, it’s a pretty big room, but I think you did it. The walls had to shake for Jack, just like they would have on one of his pages.

An age passes with Jack Kirby. Us comics folks, we’re all fond of naming “ages” of comics. We’ve come up with a halfdozen names for them in the last half — dozen years. But a very big age of comics is coming to an end now, and, I’ve got to say, I can’t call it the Marvel Age of Comics, because I don’t believe in rewarding thievery. I call it the Jack Kirby Age of Comics.

By saying this, I mean no disrespect to the outstanding and remarkable works of Stan Lee and Steve Ditko and many others. We are in their debt as well. But it was Jack Kirby who defined the style and method of every comics artist who followed him. There is before Kirby, and after Kirby. One age does not resemble the other.

The King is dead. There is no successor to that title. We will never see his like again.

There are many others we should honor tonight. Too many, far too many. Comics have been around long enough for us to lose the generation that gave us the art form and the industry we celebrate tonight. They leave us with their example of the best thing about our weird little corner of art and commerce: their love, their love of comics.

For most of you and me here, I know that love has been lifelong. And to our families, schoolmates, and acquaintances, it’s seemed a little unnatural, hasn’t it? It’s always seemed a little weird, hasn’t it? Bear with me while I tell you about Frankie Markham, and how I fell in love with comics.

I was a skinny kid in grade school. The gangly kind of kid who grows tall too fast and falls down too much playing softball. Frankie Markham was my nemesis. Frankie Markham was mean and ugly and a number of years older than me, a tough-ass farm boy, a bully. He must’ve been all of twelve years old. You know what I mean. A grown-up.

Me, I started out wanting to be Superboy. My mom was kind enough to sew me a Superboy suit, and I often wore it under my school clothes. Only to a crowd like this would I admit that.

There came the day when I had to stop being Superboy. That was the day Frankie Markham slapped me around and punched out my buddy Craig. He punched him so hard it dislodged his braces. Craig was a bloody mess, and I was bawling like a baby. It was all could do, bawl like a baby.

The fantasy was shattered. Superboy would’ve flattened Frankie Markham, or at least used his heat vision. I knew that I couldn’t be Superboy anymore. It was time for this third grader to grow up, so I did. With a new, pragmatic world view, I did the realistic thing. The mature thing. The grown-up thing: I decided I was Spider-Man.

Spider-Man had trouble with bullies, too. They embarrassed him in front of girls. They called him names. But he put up with it, concealing the secret of his awesome power. He put up with it and put up with it, just like me, he put up with it and put up with it, until —

And now my story moves towards its sense-shattering climax. At least I wish it did. I’d love to say that I kicked Frankie Markham’s ass from Vermont to Wisconsin, but I never did that. I never had a fight with Frankie Markham, and I’d have lost it if I had. But I did learn to fight back against the bullies, with my fists and my wits, and Spider-Man helped. I gained courage, I learned to control my arms and legs, and I fought back. Somewhere along the way I even earned Frankie Markham’s respect.

And Spider-Man helped.

It was years later, the last time I saw Frankie Markham. I was driving then, so I must have been about 17 years old. I was driving down some back road of Vermont, and there he was standing by the road, hitchhiking. I pulled over and picked him up and drove him over to some other back road. On the way, he told me that he’d heard I was moving to New York City, and that I was going to become a comic-book artist. He thought that was really cool.

I let him off. I watched him lumber off. I watched Frankie Markham lumber off, down that back road. My old nemesis. All of a sudden he seemed small and sad. Not very often at all, I wonder about what happened to Frankie Markham.

Comics have always been desperately important to me. As a refuge. As inspiration. As a vehicle for my fantasies. As a career. I know I’m not alone, not in this room, in loving what comics are and what they can do. It’s that love that built this industry.

Jack Kirby was the biggest and brightest of a generation that brought so much love to the page that our entire industry is built upon it. It was an amazing generation. An epic generation. When you think about what they did … They clawed their way out of the Great Depression. Just this month, we were celebrating how they stormed the beaches of Normandy, beat Hitler, and quite literally saved the world. And along the way, they, in their generosity, gave us the comic book.

And now I’m lucky enough to be enough of a player in this field to be invited to speak to you all about the future of comics. And I will. But there’s no way to talk about the future of comics without addressing its past. There’s no way to properly understand where we are now and where we are going without looking at where we have been — and our history is so clouded by misconceptions and outright lies that I have to dispel a few of them just to help us all think straight.

Too often our villains have written our history. It’s very important that we keep in mind that up until very recently everything that’s been any damn good about comics has been done in spite of the rules of the game, not because of them. Men like Jack Kirby and Joe [Shuster] and Jerry Siegel and Wallace Wood and Steve Ditko — they brought such generous love to the page, and such joy to our lives, and so much money to our bank accounts, that it is easy to forget, way too easy to forget, that they were treated disgracefully.

Ours is a sad, sorry history. We have to keep that in mind while we’re in this room enjoying this. It’s a story of broken lives. Of suicides. Of brilliant talents treated like galley slaves. Talents denied the legal authorship of what they created with their own hands and minds. Ignored or treated as nuisances while their creations went on to make millions and millions of dollars.

An industry kept alive by love, in spite of all this. The love they gave the page. It’s a powerful thing. We must honor our dead, and we must understand our history. We cannot move forward without looking very clearly at where we have been.

Misconceptions. Outright lies.

Misconceptions. Here’s a whopper. One that has cost us dearly. The dreaded 1950s. Fredric Wertham. The outside world. It seems a week doesn’t go by where I don’t sit down with my Comics Buyer’s Guide and read about somebody, somewhere, fretting about the almighty outside world and how it is bound to notice our adventures are getting more adventurous. Nobody’s come after us in any big way, but there’s a little bit of the stink of censorship in the air, isn’t there? There’s all this noise about Janet Reno and Paul Simon and Beavis & Butt-Head, isn’t there? And we all know what happened last time, don’t we? In the fifties, with Frederic Wertham and the Senate hearings. They shut us down, didn’t they?

The outside world went and noticed us. The United States Senate held hearings and decided comic books caused juvenile delinquency, right? So we had to institute the Comics Code, right? Our backs were against the wall, right?

Wrong. Dead wrong. They didn’t. The Senate vindicated us. Frederic Wertham failed.

This is how screwy our sense of our own history is. Most people in comics don’t realize that the Senate vindicated us. After due consideration, the United States Senate decided comic books were not a cause of juvenile delinquency. We were vindicated.

Why, then, the Comics Code? Abject cowardice, maybe? Maybe, partly, but not entirely.

We were vindicated. Why did the comics industry go and adopt a code of self-censorship far stricter than any in entertainment? Why would a healthy, vital industry selling comics by the truckload — hell, by the trainload — and castrate itself? Why?

The answer may just make you all a little sick to your stomachs. You see, comics publishers in the 1950s had a problem. This problem had a name. Its name was William Gaines.

William M. Gaines was the rarest of creatures, a brilliant publisher. His EC Comics outsold everybody else’s comics by a long shot because they were better than anybody else’s comics. By a long shot. The other publishers couldn’t compete with him. Not fairly, anyway. So they used the free-floating fear of the time to shut him down. If you read the Comics Code — and I have — you’ll see that it was written with no purpose more noble than driving EC Comics out of business. That was its purpose, and it succeeded at it [waving a copy of Americana in Four Colors, a booklet published by the Comics Code].

I can back this up. I’ve got a copy of the Comics Code right here [ripping the cover off the booklet].

Excuse me, but I’m having some trouble opening it. Here are a couple of examples of the Comics Code. General Standards, Part A, Paragraph 11: “The letters of the word ‘crime’ should never be greater appreciably in dimension than other words contained on a cover. The word ‘crime’ should never appear alone on a cover.” See ya, Johnny Craig [ripping pages from the booklet, throwing them away].

And here is General Standards, Part B, Paragraph A: “No comic magazine shall use the word ‘horror’ or ‘terror’ in its title.”

A noble effort, folks.

That’s why we had that damn stupid Comics Code for all these years. Not to protect children. Not to satisfy the United States Senate. Not to mollify Frederic Wertham. We were stuck with the Comics Code for all those dumb decades because a pack of lousy comics publishers in the ’50s wanted to shut down Bill Gaines.

Misconceptions. That one continues to haunt us. Because of something that never happened, our industry cringes like a battered child every time there’s a hint of a threat from the outside world. Every few years, the fear talk starts again. Every few years, the producers of stories about heroes who never give up start whimpering that we should fold up our tents and surrender to an enemy who hasn’t even shown up.

These days, the fashionable form of self-censorship is a rating system, so that’s what people suggest. Cover advisories are waved like a magic wand that will chase away the censors. Cover advisories. Little apologies printed on the corner of covers. Nobody will bother us if we apologize … if the storm troopers come after us, we’ll be safe if we say we’re sorry …

Come on! What kind of self-delusion is that? Did cover advisories help Omaha the Cat Dancer or Yummy Fur or any of the other comics seized in busts? No! It pointed them out, if anything. That’s the first reason why cover advisories are a bad idea: they simply don’t work. All they do is save the censors a little time.

Please understand: I believe you should know what you’re ordering. Solicitation forms should tell you if a given comic might be trouble, so you can make your informed choice in your shop in your community as to how you want to handle the comic — or if you want to carry it at all. That’s your decision. And it’s my duty to put together my comic so that the format, the price point, and the cover honestly represent the contents.

It’s a matter of choices, yours and mine, and whether or not we’ll be left free to make our own.

I know I’m not out there on the front lines like you all are. Nobody’s going to storm into my studio and take my brushes and pens and paper away. But we are in this together, and when you lose, I lose.

That’s why I’m happy to report that I’ve been given at least some opportunity to help. Denis Kitchen broke the cowardly tradition of comics history by creating the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, the first organization designed to fight censorship rather than surrender to it. Denis invited me to join its board of directors, and, not giving them a chance to come to their senses, I accepted the post.

We have to be brave, when and if the censors come. We have to stand up and stand together and give the bully a bloody nose. Apologies will only encourage the Frankie Markhams out there to come back for more.

There’s another reason, more serious and more subtle, why cover advisories are the first step toward disaster in our future. We are not part of the electronic media. We don’t play the same game with the censors that Hollywood does. We’re part of a smaller, better industry: publishing.

Bookstores don’t apologize for selling books for adults. Writers of prose don’t submit their works to a pack of rating system bureaucrats, or sit down with their notepad or computer when they get a good idea and think “are we talking about an ‘R’ here?” Book publishers use the First Amendment of the United States Constitution as a shield against censorship.

Cover advisories have a corrosive effect. I’ll be bold enough to say that every time a publisher uses one — every time an artist allows a cover advisory on his work — he is, in a small way, cutting away at the tether that connects us to the book industry and its First Amendment protection. Every cover advisory is a signal to lazy parents and opportunistic politicians that we are theirs for the taking.

We’re better than that. We’ve got too much love for that. We won’t let misconceptions about our own history ruin our own future. We’re better than that.

Misconceptions. Outright lies. Too often our history has been written by its villains.

Lies. Here’s a string of them, and all about the same man: Neal Adams is crazy. Neal Adams just didn’t like to work. Neal Adams was just being a troublemaker.

I can testify, as a firsthand witness: if there’s ever an accurate history of comics written, Neal Adams will be recognized not just as a brilliant and influential artist, but as a visionary, as a pioneer. As one of the heroes of the field. And if our future is as bright as I believe it can be, Neal Adams will be appreciated as the man who helped us turn a crucial corner toward that future.

I was there. I can testify. Neal Adams recognized that the talent was treated disgracefully. As much as he loved the doing of comics — l’ve never seen anybody work harder! Anybody who saw him can testify to this. Even the flu didn’t stop this guy — as much as he loved the doing, Neal was willing to sacrifice hours and days that amounted to years of a brilliant career, all to gain some measure of justice for Siegel and [Shuster] and others.

These days, cartoonists negotiate over how high a royalty is to be paid, not whether or not any will be paid at all. Neal came into a field where royalties were unheard of. A field where publishers routinely allowed original artwork to be stolen or shredded — did you know that at least one major publisher used to routinely shred the original artwork?

Picture something from the Golden Age. Something by your favorite artist. Joe Kubert, whoever, Carmine Infantino. Back then the originals were bigger [gesturing to indicate page size]. Now imagine taking this Joe Kubert page, and shoving it into a shredder and watching the little fingers come out the other end [miming action described]. I’ve just described to you the first work that one publisher gave to several comic book writers I know.

Neal was one of the very few people who helped change all this — and along the way, he taught a younger generation, my generation, that our work was worthy of respect. That our efforts deserved to be rewarded. That our families need not go hungry while our creations went on to make millions.

He taught me. He showed me that company loyalty at that time was an oxymoron that only a moron could believe. He had to be very patient. We don’t really learn until it happens to us, do we? And there’s always that little voice that says, “That was a long time ago, what they did to Siegel and [Shuster] and Kirby and Ditko… ”

So it’s no wonder that a lot of us were surprised when we learned that seventeen years of loyal service and spectacular sales didn’t buy Chris Claremont one whit of loyalty from Marvel Comics.

That was just one of many lessons learned by my generation, and now that we’ve learned them, it’s astounding to find out how many allies Neal Adams had — and how well they disguised themselves. A few months ago, I read a release from Defiant Comics and found out that Jim Shooter has spent his whole career fighting for creators’ rights. You could have knocked me over with a feather.

I knew Shooter was talented and accomplished. I knew he had something to do with the Legion of Super-Heroes. I had no idea he was Duo Damsel.

Misconceptions. Lies.

Here’s one lie you can almost forgive, given the current condition of its source. Marvel Comics is trying to sell you all on the notion that the characters are the only important component in comics. As if nobody ever had to create those characters. As if the audience is so brain-dead it can’t tell a good job from a bad one. You can almost forgive them this, since their characters aren’t leaving them in droves like the talent is.

For me, it’s a bit of a relief to finally see Marvel’s old work-made-for-hire, talent-don’t-matter mentality put to the test. We’ve all seen the results. They aren’t even rearranging the deck chairs.

And the way Marvel’s treating you all — the things I’ve been hearing about… I’d half expect that if I snuck past Terry Stewart’s secretary and through his office and into the board room and saw who the real boss is at Marvel, I might just find out what happened to Frankie Markham after all!

Marvel Comics has been caught flat-footed and dumbstruck by a sea change in our industry. They are paying the price for separating the talent from the characters. As if one is worth a damn without the other. They’re showing why creator ownership is so important, not just to me — that’s obvious — but to you as well.

Work-made-for-hire isn’t just bad for artists. It’s bad for business. Your business.

When I’m out on the road at conventions or store signings, there’s one question I get asked just about every time. Comics fans are generally a very polite bunch, but some anger usually shows when they ask this question:

“How come people don’t stay on books?”

“We loved your Batman. Why didn’t you stay? We loved your Daredevil. Why didn’t you stay?”

There’s a whole pile of answers to that one. You run out of steam. You have a fight with your collaborator. Blah, blah, blah. Things happen. But the main reason a lot of us leave best-selling titles for work-made-for-hire publishers is simple: You get sick of feeling like a schmuck.

Don’t get me wrong, here. Like everybody else of my generation, I knew the score coming in. I knew that I was playing with the company’s toys. I knew that any characters I created would be turned into cannon fodder for other people. I knew that when I was promised that nobody else would be allowed to write Elektra, I knew that promise would be kept right up until the moment it was convenient for them to break it, which is exactly what they did. I knew all my efforts wouldn’t amount to a hill of beans if some editor wanted my job. or had a buddy who did, and fired me. No matter how well the book was selling.

Don’t take my word for that one. Ask Chris Claremont. Ask Louise Simonson. Ask Jo Duffy.

Yeah, I knew all that. And I knew that I was strip-mining the past instead of building the future. That was the game, and I knew it, and I played it, and I had a ball. But after a while I did start feeling like a schmuck. So I took the risk and broke away and signed on with a younger publisher, Dark Horse, one of many new publishers who has come along to offer better terms. Publishers not trapped in the old grab-it-all, keep-it-all ways.

And I’m happier now than I’ve ever been. I own Sin City. Nothing can be done with Sin City without my permission. I can’t keep my hands off Sin City. I love Sin City. The love we give the page. It’s a powerful thing.

And now I can finally give that angry fan an answer he might like. An answer I could never have given him before.

If it’s Sin City, I write it. If it’s Sin City, I draw it. That’s a promise. No exceptions. No fill-in issues. That’s a promise. It’s a promise I can make only because I own Sin City.

The creator bound to his creation. The creator in charge of his creation. It’s better for me, and it’s better for you. Things are on their way to getting a whole lot better for both of us. But, still, the old, fearful mindset persists. The old self-contempt. And never has it been more shamelessly displayed than in the resentment and hatred that’s been aimed at Image Comics.

For decades, rotten business practices caused a steady, slow brain drain, driving talent away one by one. One by one. Each individual artist or writer, more or less replaceable. There were always new kids to come along and feed the machine.

Then along came ringmaster Todd McFarlane and his amazing friends. Instant millionaires, I’m told. Their popularity at a fever pitch. They had it made. They had money. They had fame. They had no reason to leave — except that they were smart enough to realize that the best you can get under work-made-for-hire is the status of a well-paid servant.

So they left. Brilliantly, they left all at once.

Consider this: Todd McFarlane and his pals turned their back on guaranteed wealth. Guaranteed fame. They risked all of that on something that had never been tried before — an imprint that represented a group of artists rather than a bankroll.

And it was a gamble. It never seems that way when a gamble works out, but I am sure Todd and Jim Lee and Rob Liefeld each had long nights, when they wondered if they’d made the biggest mistake of their lives.

They gambled and won. They shattered the work-made-for-hire mentality, showing how unnecessary it is. Even more surprisingly, they broke Marvel’s stranglehold on the marketplace. The kids went with them.

And people hate them for it.

Consider this: The best-selling comic book in the country is creator-owned. And artists aren’t celebrating. Too many of us are acting like galley slaves complaining that the boat is leaking.

Consider this: I wrote an issue of Spawn and was called a sellout — but nobody called me a sellout when I did Dark Knight and made more money from Batman than Bill Finger, Jerry Robinson, and Dick Sprang ever made combined.

Consider this: Because of Image Comics, artists enjoy new opportunities and are paid better, even at Marvel Comics.

And nobody’s said “thank you.”

Let me be the first, then. Gentlemen. Thank you.

And, speaking as one of us who was out in the trenches a few years earlier, you’re welcome, too.

And now Image has inspired Legend and Bravura and, I’m sure, other talent-based imprints to come. We are headed for better times and better comics.

There are new self-publishers, and new publishers ready to offer fair and honorable terms. New homes for new creations — in a field that has been starving for something new and fresh. The future of comics.

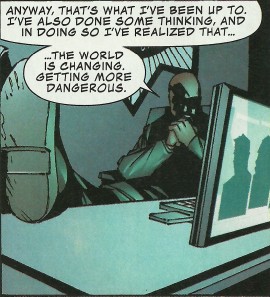

I know this has been a scary time for many of you, maybe all of you. The Marvel Age of superhero universes, the Jack Kirby Age of Comics, is coming to an end. It’s gone supernova and burned itself out and begun its slow, steady collapse into a black hole.

We couldn’t feed off the genius of Jack Kirby forever. The King is dead, and he has no successor. We will never see his like again. No single artist will replace him. No art form can expect to be gifted with more than one talent as brilliant as his. The rest of us, we will build upon what he gave us. We’ll bring our best efforts, our own quirky, mischievous, and rude efforts. We’ll screw up, we’ll get lucky, we’ll do right, we’ll do wrong. We’ll make comics that are diverse and wild. We’ll take chances.

We’ll need you to take chances, too. When you hear about next week’s new work-made-for-hire superhero universe, please don’t stifle that yawn. Take a chance on the new comics. Look for the ones where the creator has every reason to stay and can’t be fired because he owns it, because it is his, and it is him.

It’s a scary time because change is always scary. But all the pieces are in place for a new, proud era, a new age of comics. And nothing’s standing in our way, nothing too awfully big. Nothing except some old, bad habits and our own fears. We won’t let them stop us. We’ll drop them off on some back road, like I did with Frankie Markham. We won’t wonder what happened to them. Not very often, we won’t. We won’t let them stop us.

I don’t post this to pretend like it’s Miller’s opinion today (though I figure it probably is still pretty close) or that it’s something I believe in 100%. I do think it’s fascinating that most of what he says still applies to the industry today. Even the Image stuff has kinda come around back to this point, with Image being new and exciting and Marvel feeling like yesterday’s toast a little too often.

It’s sort of depressing, actually. Legend and Bravura are no more, though a few of those guys are still making new work. We didn’t really enter a new age, as near as I can tell, as let the Jack Kirby Age limp on and on while the real world caught up to comics. Comics was forced into a new age, instead of pioneering a new one. Manga, webcomics, the internet as a discussion and delivery system, archival projects, book publishers taking notice… I don’t think Miller, or anyone, saw any of that coming, and Miller even had a hand in trying to get manga mainstream over here.

I’m maybe being unfair when I say it was forced into a new age, though. I thought of Image publisher Eric Stephenson’s post about the past twenty years in new comics while I was editing this, both as counterpoint and complement, and I realized that we’ve got a wealth of great comics now and an incredible comics culture. Maybe The Jack Kirby Age went away and now we’re in… I don’t know, I hesitate to name it because it’s so formless and open. The Chaotic Age of Comics.

Anything goes. I’ve spent the past couple weeks obsessing over Leiji Matsumoto (who has skipped in and out of the conversations I’ve been having online), reading One Piece and Toriko a couple weeks after they’re published in Japan, plotting the best way to binge on these three Peanuts hardcovers I have without burning myself out (I think burnout is impossible, but anything can happen), gawking at art books by Katsuhiro Otomo and Katsuya Terada, checking out the Extreme relaunch (which is introducing me to new artists), buying old Frank Miller/Bill Sienkiewicz comics used off the internet, reading Moebius and Jodorowsky’s The Incal

hardcovers I have without burning myself out (I think burnout is impossible, but anything can happen), gawking at art books by Katsuhiro Otomo and Katsuya Terada, checking out the Extreme relaunch (which is introducing me to new artists), buying old Frank Miller/Bill Sienkiewicz comics used off the internet, reading Moebius and Jodorowsky’s The Incal for the first time ever, stocking up on 2000 AD, and more besides. I know the specifics of what I’ve been consuming are pretty idiosyncratic, but I don’t think my habits (the fact that I’m pulling from then and now and here and there simultaneously) are that weird, are they? Maybe that’s selection bias, but most people I know take in all types of comics from various periods of time. Even the cape lifers mix it up.

for the first time ever, stocking up on 2000 AD, and more besides. I know the specifics of what I’ve been consuming are pretty idiosyncratic, but I don’t think my habits (the fact that I’m pulling from then and now and here and there simultaneously) are that weird, are they? Maybe that’s selection bias, but most people I know take in all types of comics from various periods of time. Even the cape lifers mix it up.

I think what I’m trying to say is that in this new, post-Kirby age, is that all, or at least a significant portion, of comics history is at my beck and call, and that the various types of comics — Japanese, European, newspaper strip, tights and fights, crime, romance — exist on basically the same plane. When I reach out to my shelf or look to my Amazon wish list, there’s this incredible spread of stuff for me to read, all of it different from its neighbors. I just went and looked at my list and like… there’s a short story manga collection, there’s a Wolverine comic I’m not gonna buy, there’s a manga about The Lourve drawn by Hirohiko Araki , a manga about geisha, a Sergio Aragones hardcover… there’s a level of choice in what’s out there for me to read that I never felt growing up. It’s spread across genre and style and country of origin, and even books that share three out of three might be totally different from each other in execution. That feels good. That feels like the epitome of what Stephenson is talking about.

, a manga about geisha, a Sergio Aragones hardcover… there’s a level of choice in what’s out there for me to read that I never felt growing up. It’s spread across genre and style and country of origin, and even books that share three out of three might be totally different from each other in execution. That feels good. That feels like the epitome of what Stephenson is talking about.

But at this point, I’m rambling and Sandman Sims is on the way to rush me offstage. I hope you found Miller’s speech interesting or enlightening, and I’m curious what you think this age of comics is defined by. For me, it’s the embarrassment of riches. Is it something else for you?

As a sidebar, this essay actually warped my understanding of exploitation in comics as I grew up. Miller’s mostly on point here, and 100% on point from an emotional/justice standpoint, I think. He’s not quite right about a few of the specifics, though, and Chris Eckert has the much-needed corrections over here and more besides. It doesn’t dilute Miller’s overall point by much, though, but it’s worth mentioning if only to keep the conversation about this basically fact-based.