One thing superhero comics have a glaring lack of are actual acting. For a wide variety of reasons, the emphasis in comics art is on figures. You need to be able to draw strong dudes, sexy ladies, and if you can manage to fit in surprise, anger, stoicism, arrogance, and something that kinda sorta resembles bedroom eyes on the figure, more power to ya, superstar. The emphasis in most books are on the figures and the costumes, with faces being a distant third at best. You’d think it wouldn’t be this way–Brian Bendis is fond of using reaction panels and Geoff Johns is doing a mega-arc based around emotions, but it is what it is.

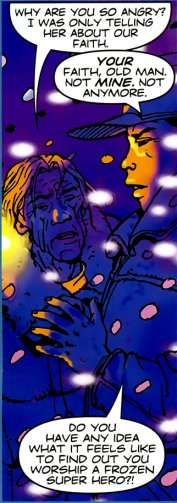

Faces are extraordinarily important when it comes to acting and body language. When people say that the eyes are the window to the soul, they’re more or less correct. The eyes are probably the most expressive thing on your face, and they change shape and appearance based on how you move your face. Look in a mirror and smile, frown, glower, or whatever and watch how your eyes move around. Obvious, right? You can smile or frown with your eyes, even when trying to keep your face expressionless.

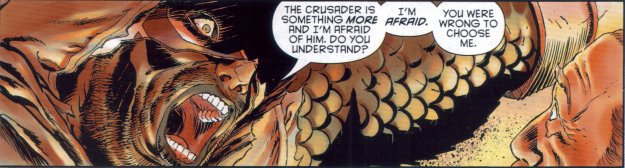

Let’s be honest here. Most facial expressions are stupid. If you ever look at someone grinning, or scowling, or screaming in terror–I mean, it looks stupid, right? The face contorts and shifts and all the muscles under the skin move around, creating hills and valleys where once were plains. Watch your friends while they laugh, especially if they do deep belly laughs. Their mouths gape open and their eyes squeeze together. (Don’t get me started on people who stick their tongue out when they laugh. I mean, where do you learn that?) Facial expressions can be movements or moments in time, and every person is different. Capturing that takes paying attention.

There are a lot of artists who don’t know what to do with a face. Ed Benes draws these empty-eyed, expressionless, hollowed out shells of characters; people who stand around with blank expressions until they get a chance to shout or shut their eyes. (Benes’s inability to draw attractive women baffles me, considering that Brazil is pretty much Pretty Woman Heaven. Go to the beach, son, draw from life.) Other artists have these set facial patterns they go for and graft onto their characters. Not Amanda Conner, though. No, she goes all-in as far as facial expressions go.

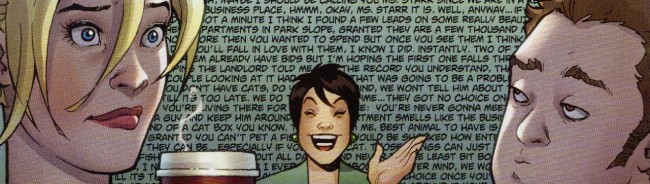

Her most recent work was a twelve issue run on Power Girl with Justin Gray and Jimmy Palmiotti. It was the DC Comics equivalent of one of Marvel’s mid-list titles like Immortal Iron Fist. It didn’t ever really tie into the overall story of the DC universe, instead picking up and running with stories about the day-to-day life of the titular character. Power Girl gave Conner plenty of room to play around with her art, using a lot of funky body language and facial expressions to push the story along.

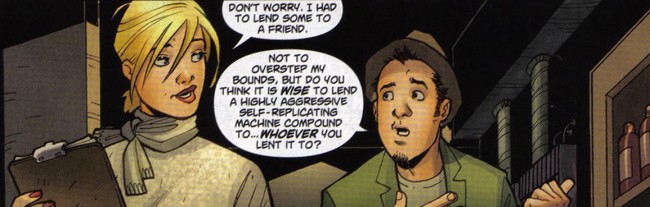

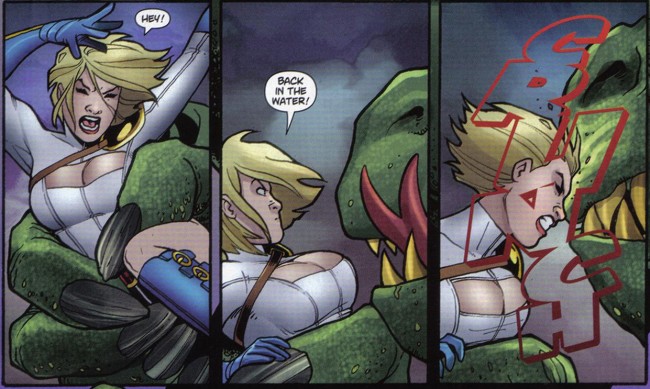

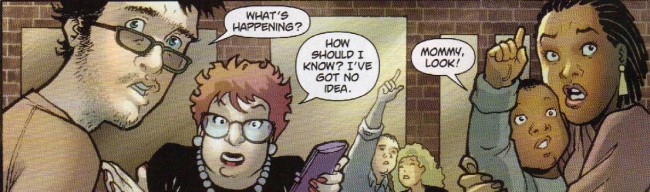

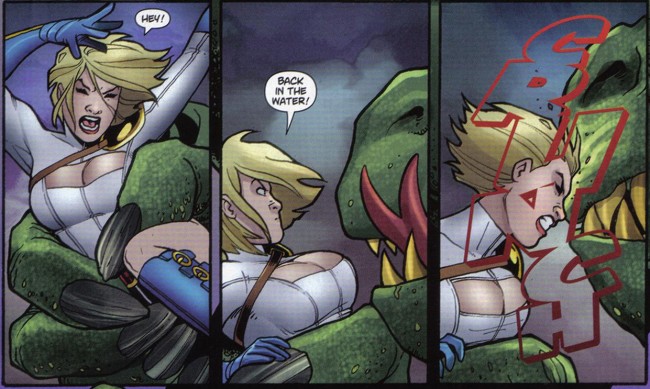

What’s interesting about acting in comics is the way it replaces dialogue and exposition. Shouts, grunts, screams, growls, and certain other noises don’t actually need the word balloon with “AHHHHH!” or “Grrr” or “sigh” to get the point across. Think of Edvard Munch’s “The Scream,” where a man standing on a bridge screams in silence. Sure, you could add some sound effects on that, preferably by John Workman, but you don’t need it. The expression is clear enough.

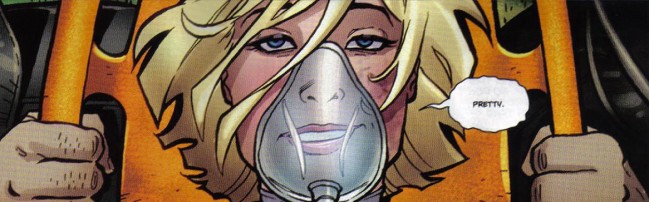

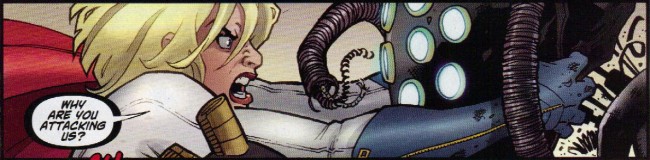

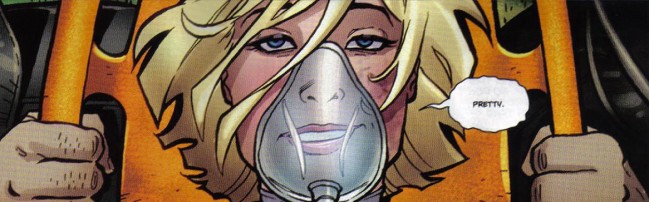

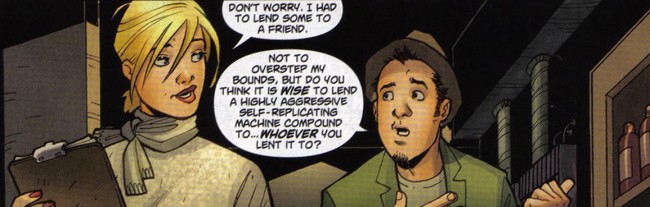

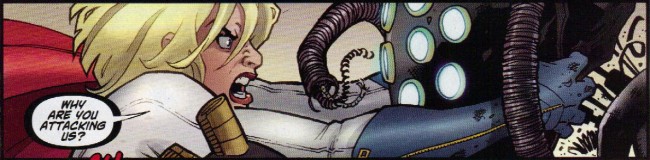

Conner incorporates this fact into her work, and Power Girl became one of DC’s strongest comics because of it. There are tons of scenes where grunts, gasps, or shouts would have been appropriate, but instead, all of the expression is left to Conner’s art. Power Girl biting her lower lip is an expression we can all understand. She’s angry and focused. With her eyes half closed and her lips molded into something like an “O,” it’s clear that she is sighing.

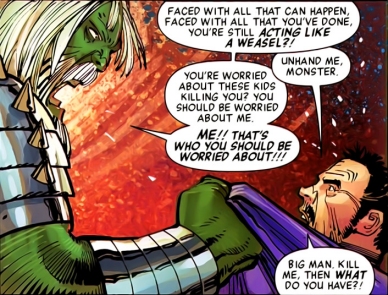

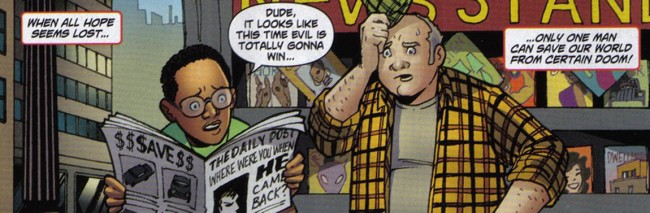

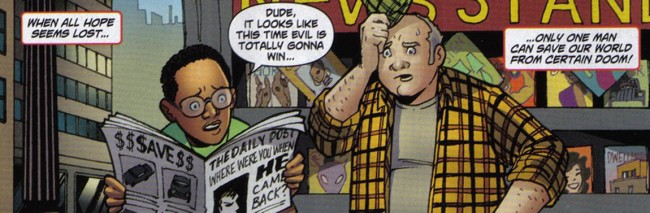

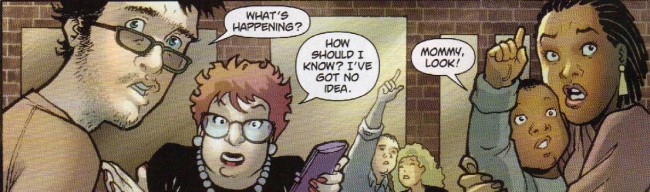

Conner’s art doesn’t stop at your usual mix of facial expressions. She runs through grumpy, happy, sleepy, bashful, sneezy, and dopey, which already puts her over and above most artists, but also throws in exasperated (my personal favorite), violently determined (as in when she scrunches her face before headbutting a monster), giddy, slack-jawed surprise, fear, bemusement, amusement, embarrassment, skepticism, irritation, and uncontrollable anger. Even that emotion that can be best surprised as what you feel when someone tells you that something was due forty-five seconds ago, that kind of “Wait… what?” feeling–it’s in there.

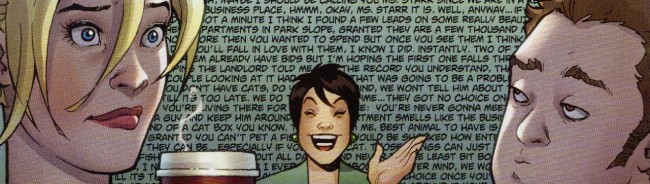

Facial expressions are just one part of acting, obviously. Body language counts for a lot, too. How close you’re standing to someone, the distance between your hands and your body when standing with your arms at your side, the tilt of your head, the angle of your shoulders, the way you clench your fist, and the width of your stance convey an astonishing amount of information. You can take in someone’s mood at a glance once you start paying attention to body language.

In comics, this is just additional storytelling. The more you can display in your art, the less you have to actually write. A cocked eyebrow, tilted head, crossed arms, and crooked mouth says, “Oh, is that so?” better than dialogue ever can. Tightly clenched fists and a scowl are extreme anger. Nervousness is a full body emotion. A goofy smile and eye contact says more about attraction than “You had me at ‘hello.'”

These are all tools in a comic artist’s repertoire, and Conner used them to their fullest in her run. There’s thirty-five images in this post, most of them single panels, and all of them pulled from the first five issues of Power Girl. Many of the faces reflect the same emotion (anger and surprise, mostly) but in a different way each time. I chose Power Girl as the example for a couple of reasons. First is that it’s her book, so she gets the majority of the attention. The other reason is to show that just because you’re focusing on one person doesn’t mean you get to come up with just one expression for each emotion.

What makes Conner such a great artist is that detailed and expressive faces, a glaring omission for most comic artists, get just as much care and attention as huge splashes or the carefully crafted contours of your average superheroine. Conner’s work on expressions and body language is a smaller reflection of the attention she pays to comics art in general. Conner’s art is focused on telling a story in the clearest and best possible way. If this means getting important information across via body language, rather than dialogue, so be it. If it means explaining a character’s personality by way of her facial expressions, rather than oodles of exposition and quips, so be it.