Gamble a Stamp 03: Superhero Comics Are Dead

October 24th, 2010 by david brothers | Tags: alan moore, dark knight returns, dave gibbons, flex mentallo, frank miller, gamble a stamp, watchmen

The story goes that Dark Knight Returns was born when Frank Miller realized that Bruce Wayne was younger than he was. This character that he’d looked up to, or at least enjoyed, since he was a kid in Vermont was suddenly younger than he was. Miller was getting old, and part of getting old is looking at the things you loved as a child stay young. The aspirational aspect of superheroes, the “Gamble a stamp!” element that makes the genre so fascinating, is a little tougher to swallow when you’re finding wrinkles in new places and Bruce Wayne is still 29 years old.

So, Miller added twenty years to the character and in doing so, plowed fresh ground. Batman became someone Miller could look up to again, with his universe and methods updated accordingly. Superstitious and cowardly criminals were replaced with a threat birthed from societal collapse and the apathy of good men. Batman turned pointedly political, and Miller took on Reagan and pop psychology over the course of DKR. He created Carrie Kelly and made her the new Robin, both updating and critiquing the Robin concept.

Getting older killed the superhero for Miller. He couldn’t relate as he once did, and he took steps to make superheroes cool one last time. Dark Knight Returns is a blaze of glory for the superhero, that last, brilliant blast of light before death. It says that these dusty old characters are still just as vibrant as they once were, but not in the same ways. People grow old and change, and their interests change with them. At the end of DKR, Batman isn’t a soldier in the war against crime like he once was, and like he is now. He was a general, as his severe turtleneck and demeanor suggests. He’s leading the war, not fighting it. He grew up.

Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’s Watchmen came from Moore wanting to write a superhero story with weight, something like Moby Dick in particular. He wanted to write a superhero for adults, and chose hard-edged pessimism to get the job done. Its rigid structure shows a world that has no use for acrobatics or melodrama. It has no place for many of the staples of cape comics, whether you prefer Jack Kirby-style action or classic stylings of Curt Swan.

Watchmen, then, is an autopsy. By the end of it, all of the secrets of the superhero are laid bare. You see the paunches and watch their muscles sag. You get a front row seat to Nite Owl’s impotence and the way superhero costumes function as fetish objects. Rorshach is revealed as being not that much better than the villains he fights. An old man gets his brains beaten out, the only true superhero is so alien as to be inhuman, and in the end, the villain wins and saves the world. The heroes? They compromised because to actually defeat the villain would have resulted in the destruction of world peace. Rorshach refuses to compromise and is killed for it.

All of your illusions and ideas of the superhero are deconstructed and proved false by Watchmen. They’re normal people, rather than superheroes, and act accordingly. There’s no magic, no aspirational aspects, and nary a wink from Superman. Just hard edges and gritty realism.

DKR is the blaze of glory. It’s a revitalization before death. Watchmen is the autopsy. At the end, there are no secrets. What’s Flex Mentallo? It’s a wake, that time when everyone gets together, gets drunk, and talks about the deceased.

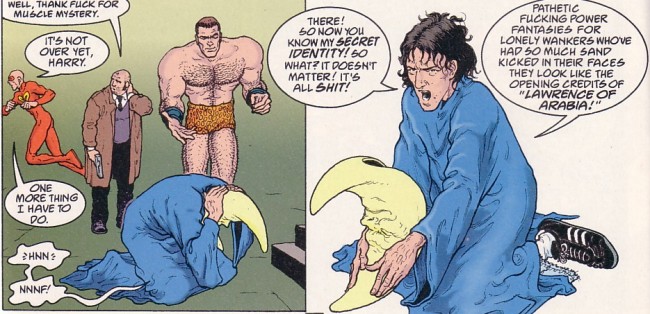

Wally Sage is overdosing on painkillers in Flex, but that’s not all he’s taken. He’s had a bottle of vodka, a couple e pills, a quarter ounce of hash, and he’s tripping on acid, too. As he’s dying, he’s talking about all the amazing comics he read. He’s talking about the good, the bad, and the irrelevant. He’s painting a picture.

The picture he’s painting is of the full spectrum of comics, or at least the full spectrum of the comics he read as a child. He talks about how exciting they were, how sexy, and how scary. He talks about how superheroes couldn’t stop his parents from fighting or save us from the bomb. Flex is about how fiction is real, and the way that the two rub up against each other and interact at certain points.

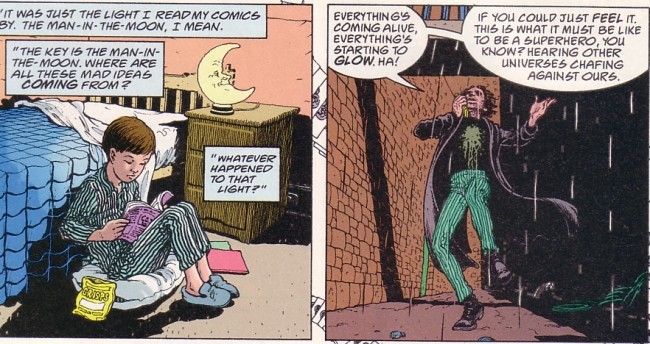

Flex Mentallo is a hopeful book. At the end, the superheroes return to save us all. They are revealed as us, or at least a significant part of us. Flex saves the day. The magic of reading superheroes as a kid is adapted to the real world. The glow of the lamp that Wally read comics by as a child serves as a blatant metaphor for the brilliance of superheroes. At the end of the book, the light is restored to Wally’s sight.

Flex is a celebration of the superhero. All of it, from good to bad, from perfections to imperfections, is important. The sexualization of superheroes serves a purpose, either as masturbation material or as an outlet for the creator’s desires. The Silver Age zaniness provided a look into other worlds, whether unsettling or fantastic. The escapism provided a look into a better world. The Starlin acid trips, the fear of the superhero, the edginess, the pointlessness, all of it matters. All of it fits together. It’s all part of the same picture. All of it is wonderful, in one way or another. It’s a puzzle with a million parts that still manages to stay in sync.

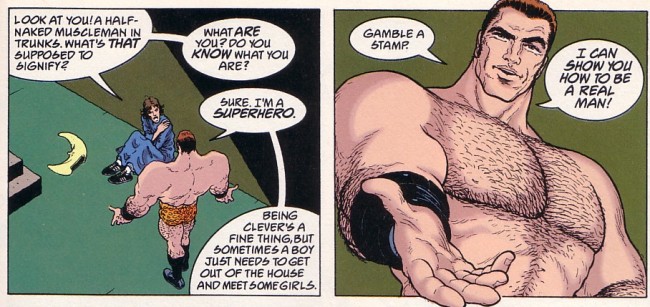

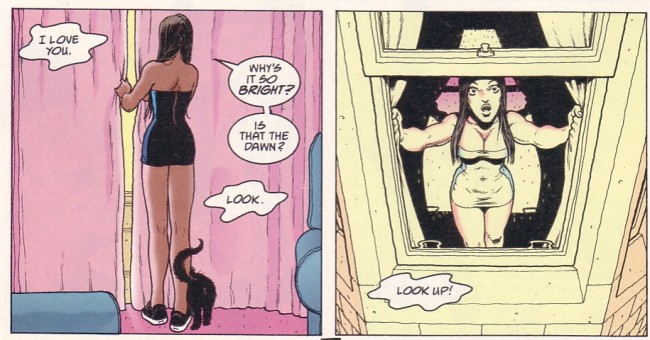

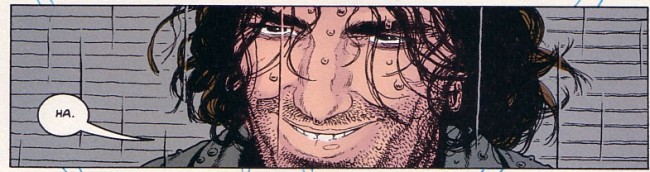

And in one of the last scenes, the point of Flex is laid bare. “Look at you! A half-naked muscleman in trunks! What’s that supposed to signify? What are you? Do you know what you are?” asks a teenaged Wally Sage. Flex shrugs and says, “Sure. I’m a superhero. Being clever’s a fine thing, but sometimes a boy just needs to get out of the house and meet some girls.”

Implicit in Dark Knight Returns, Watchmen, and Flex Mentallo is a critique of the superhero. DKR teaches that the superhero is broken and it must be made cool again. Watchmen teaches that the superhero is broken, and here is how it is broken. Flex teaches that superheroes are broken, but that brokenness is just as natural as the parts which aren’t broken. Blaze of glory, autopsy, wake.

well david (i can call you david ?) i have to simply say, thank you.

your gamble a stamp are some of the most interesting article i’ve ever read about comics. deep but focused on our beloved medium with clear exemples,not perverted to support one thesis ( as happen with WATCHMEN, a lot).

Also as italian the first time i red flex mentallo i lost a lot of it, get bored and dropped it, now thank to your articles i found a comic that i can finally understand and truly enjoy !

For me personally Flex acts as a Resurrection. As you said it contains everything about these comics we love and why we love them, the good the bad the questionable all or nothing.

Clap your hands if you believe in Superheroes!

Nice article, but tempered by the fact that I can’t actually read the comic which kind of sucks.

Yes, the argument loses something by being bracketed within panels from a pretentious and overwritten story.

Yeah, I’m in the “Flex is a resurrection” camp. I mean, those panels are on point and everything, but young Wally Sage there is the villain. He’s wrong, and all the superheroes and older Wally team up to tell him “yes, that’s very nice how you think superheroes are outdated and gritty realism is the order of the day, but you’re pretty much just an asshole. Superheroes are awesome, stop imposing your own issues on them and let them be awesome again. Everything will be better now. Look up!”

@arancia: Thanks for reading, I hope you enjoy the rest, too.

@Joe S. Walker: Do tell.

Excellent article, David. And a timely one for myself personally.

I’m 30 and have fallen out of favor with superheroes as they are written today for several years now. Some of it has to do with me getting older and having found other comics and books to read. And besides, there are hardly any entry points for me to even want to try new superhero books. However, I do find that in reading my superhero back issues from 25 years ago and beyond, those depictions reconcile my superhero fix for me. Even down to the more insipid back issues in my collection, those work better for me now than most superhero books written today.

And in a way, those books took superheroes way more seriously than anything written today. By seriously, I don’t mean the way postmodernist superhero stories continue to ask ‘How would that really work in the real world?’. Really, who cares? Rather, I mean that those older back issues accepted these characters for the world that they inhabited. The stories have resonance for me because they are not trying to reach beyond that world.

While I can definitely agree with the wake analogy, I also think that Flex serves as the moment where, after lamenting the loss of the superhero and remembering all the good times you had together, you go to the tomb and find it empty.

They are not dead, they are risen.

I think its key, when discussing the differences between Moore, Miller, and Morrison, you have to look at how they interpret Superman. Moore’s Superman is always focused on the “world” of Superman. Moore has always been interested in the world-building aspects and when you look at something like “Superman Swamp Thing Annual” or “For the Man who has Everything” it is all about the relationships between Superman and how he interacts with the people around him. Moore’s Superman world is a world of connections and synchronicity, where everything happens for a reason. Miller’s world is one that is always critical of higher powers. His question is always the Conan question of whether a man is naturally predisposed to violence or towards peace. You can easily see this in Superman who finds peace in conformity and who has to, in the end, learn to be violent and Conan-esque like Batman. Unlike Moore and Miller, who focus on ideology, Superman always represents the common man mythologized into the Superman. Buddy Baker is one of the best examples of this, but you can really see this in All Star Superman which mythologizes the modern man’s mid-life crisis. Superman is dealing with his own mortality, doing the best he can and dealing, mostly, with the psychological issues of age and death.

While I think the critique of the Superhero is there in each of their pieces, I don’t necessarily see them as critiquing Superheroes, but rather the modern man who lives in an industrialized world. If they were writing television today, Moore would be writing for the Wire (synchronicity and relationships), Miller would be writing for the Sopranos (nature of man towards civilization or towards savagery), and Morrison would be writing for the Office (empathy and mythologization of the modern man).

That’s the staying power of Miller, Moore, and Morrison’s work: they’re talking about us and not just about superheroes.

@garyancheta:

Nicely said, Gary.

@garyancheta:

Morrison writing for the Office? The UK version, right?

Well, it’s almost a certainty that Morrison would ultimately consider Flex a resurrection, but I’d argue *via* a wake.

I love how you’re pushing for Flex’s inclusion in the canon of the genre’s must reads, David. If only someone could get the bloody thing republished.

You resurrection guys have a good point, and in a neat bit of synchronicity, I recently read Peter Milligan, Brett Ewins, and Steve Dillon’s Skreemer, which features Finnegan’s Wake as a plot point/device, which ends when a man gets up at his own wake and says “Do ye think I’m dead?”

I have to ask, is Flex Mentallo #1 in the series of number themed articles you had written about?

I’m curious, but what comes after Flex? If Watchmen is the autopsy, Dark Knight is the blaze of Glory, and Flex Mentallo is the glorious wake for the resurrection, what is the chapter in superheroes that comes after this? What is the work that is the “resurrection?”

I’ve always thought that Warren Ellis’ Planetary is the “resurrection.” Planetary, falls again with a post-911 ethic of “Saving the Planet” by saving the fictions of the planet. In each story, the Planetary Investigation team learns a new facet of their fictional world and how it filters into a superhero text. It takes the notion of Watchmen’s autopsy and Miller’s wake, then converts it into Morrison’s hopeful outlook. The purpose is that after each issue, which tackles a genre of fiction, film, or comics genre, you realize how special the original text used to be.

Ellis always approaches superheroes as a way to use “fiction as technology.” Past fictions are the raw materials for new fictions. Ellis uses this notion of “fiction as technology” as a way to critique the text. He frames the characters as archeologists that excavate things old things that people assume are dead and we learn, later, that they are really alive. The Spectre becomes Chow Yun Fat, The Fantastic Four become an evil Baby Boomer Corporation, the Alien Monster in a new world becomes a Fictionaut.

If Watchmen, Dark Knight, and Flex Mentallo is Post-Modernist (i.e. stories that are self-reflexive and comment on the text), then Planetary is Post-Structuralist. In Post-Structuralism, you have an analysis of text that breaks down the power structure within the text and exposes the relationships of these texts to a singular ideal that is relevant to the time it was created and today.

After Planetary, I just can’t think of any other text that is the next progression. What is the Post-Structuralist Superhero story beyond Watchmen? I’m thinking that we’ll see this soon from Johnathan Hickman. His SHIELD seems to approach this ideal, but I’m not sure what else falls into this category? What comes after the resurrection?

Equal parts Morrison JLA / Ellis StormWatch/Authority. Planetary is way to much of a mixed bag at least for me.

All Star Superman 10 comes next.

Obviously.

While I concur that both Morrison’s JLA and All Star Superman are great, I was trying to think of another author that does post-structuralism. Post Structuralism is very specific, looking at culture within historical context as a critique. Planetary fits this bill and so does League of Extraordinary Gentlemen and Morrisons’ Batman, Seven Soldiers, and Final Crisis because all of them deal with a critique of a genre that deals with the historical context. I just don’t know anyone else doing something similar with the genre. John Ridlsy’s The American Way seems to take this tact, by using superheroes in a historical context that critiques the genre and the age it is presented in. Hickman comes close in SHIELD, a vox populi exploration of Marvel’s past in a similar fashion to Da Vinci Code.

I think you’re a bit too wedded to theory, Gary. I also see very little cause to seek out post-structuralist texts to fill the next spot. Mind you, I’m also not inclined to take the teleological aspects of David’s post too seriously, so perhaps I’m in the wrong conversation.

@Discount Lad: Nope. I dunno if there is a number one, honestly.

@gary: I don’t know what’s next, but it’s definitely not Planetary. It’s an interesting book, but gets exponentially less interesting as time goes on, until in the end, it’s a bit crap. I’m fine leaving at just these three, as far as this argument goes. And none of them are the end of the superhero, of course, as all three could give birth to stories that walk in similar lanes with very little trouble. Energy cannot be created or destroyed, it only changes form, etc. This is just an interesting way to look at all three books.

But seriously, not Planetary or SHIELD. And too much theory saps all of the enjoyment out of stuff for me, my eyes glaze over when I read things like “post-structuralist.”

@Zom: If anything came next, it’d be All-Star Superman 10. And odds are good that I’m doing ASS 10 vs Flex (or maybe ASS 10 x Flex) next, but not in terms of what they represent to the comics canon, for lack of a better word.

Brilliant piece. If we label Watchmen as the literary deconstruction of the superhero, Flex Mentallo has to be a response piece, as a comic-booky reconstruction. I see the wake thing, but in terms of Morrison using Flex to purge all the bullshit barnacles that had stuck onto the superhero concept, and launching it into a (pardon this) brand new day. Of course, no one took him up on it, so he had to do it again with All Star Superman.

[…] continues his “Gamble a Stamp” series pivoting around Flex Mentallo with a piece on the death of superhero comics: [Dark Knight Returns] is the blaze of glory. It’s a revitalization before death. Watchmen is the […]

very nicely worked through, david. I haven’t come to similar conclusions before mainly because I’ve never read Flex! Without it being in trade (and reprint upon reprint) it doesn’t get nearly as much airtime in discussion. Maybe your piece here will help in some way towards finally getting it collected.

Until then, I guess we’ll have this amazon monument to what should have been:

http://www.amazon.com/Flex-Mentallo-Man-Muscle-Mystery/dp/1563894084

[…] In it this column, he discusses Watchmen, The Dark Knight Returns, and Flex Mentallo as elements in the death and rebirth of the superhero mythos. Excellent stuff and well written – I feel like I’d delude his points by quoting in partial. So head over there and read Superhero Comics Are Dead. […]

@Dylan: Dylan and I have discussed this somewhat at length and agreed that the ending of Flex is when you find the tomb empty and All Star Superman is the resurrection that encapsulates all of the wonderful and bizarre aspects of superhero comics into one perfect amalgam.