Booze, Broads, & Bullets: All-Star Batman and Robin, The Boy Wonder

April 17th, 2010 Posted by david brothersChad wants to talk about Booze, Broads, & Bullets. Sean wants to talk about Daredevil: Love and War and Dark Knight Strikes Again. Me? I’ve just got an index and some words about Miller’s second-most hated.

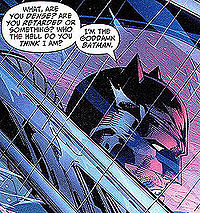

Behold, I teach you the Batman.

Batman’s story is fundamentally about revenge. He was wronged as a child and dedicates his life to the get-back. Joe Chill, for various reasons, is beyond his grasp. He can never have his actual revenge. Either Chill is dead, too old, or simply doesn’t exist. So, instead of having an explicit goal for his revenge, something he can point to when finished and have some sense of accomplishment or closure, he’s left with a phantom, something he’ll never be able to grasp. The object of his hatred is transferred to “crime” itself, and thus begins his never-ending quest to get back at the world for the death of his parents.

Batman would not be a pleasant person to be around. He’s been training to fight crime since he was a teenager, at the latest, and that kind of focus does not lend itself to being a particularly good friend. He has focused his life on figuring out ways to solve mysteries, memorizing facts about decomposition, learning ways to hurt people, and make them fear him.

Now imagine if, after being brutalized on his first night out fighting crime, he found a lens to focus his vengeance. A variation on the last happy moment from before his life was ruined. Zorro re-imagined in a blood-soaked haze. “Yes. Father. I shall become a bat.” He is rich enough to do anything, save for overcome the heartache that infected him as a child. So, he lashes out.

A child’s fantasy becomes corrupted due to unimaginable pain. The moment his parents died, Bruce Wayne’s childhood stopped and the seed that would grow to be the Batman began, nourished by blood and anger. He’s going to become a force of nature, something that strikes from the darkness and has no more substance than a shadow. But, not the swashbuckler with a sense of humor from the movies. No, when the Batman laughs, it is a bad thing. That just means the pain is coming. And he’s going to hurt you because he was hurt as a child. This is the Batman.

All-Star Batman and Robin, the Boy Wonder is the story of how Batman learned to be human. Follow along.

One thing I haven’t seen anyone address is how Batman is treated in the text. The Batman of the early ’00s, who alienated his friends and allies simply because he could, was still treated as a hero and morally correct. The Batman of ASBAR, on the other hand, is actively disliked by everyone he interacts with. In the first conversation he has with Dick Grayson, age twelve, Dick realizes that Batman is putting on a voice. “It’s like he’s doing some lameass Clint Eastwood impression. That’s not his real voice. He’s faking it.” Later, when Batman tells him that the car is called “the Batmobile,” Dick rolls his eyes and says, “That is totally queer. :rolleyes:”

Alfred, after being ordered to let the boy eat rats, declares that he is not Batman’s slave. He vehemently objects to Batman’s treatment of the child. Jim Gordon, the closest thing Batman has to a friend, mocks him after doing him a favor and receiving no thanks in return. “Of COURSE not,” he thinks. “That’s hardly be GRIM AND GRITTY, would it?” An inexplicably Irish Black Canary echoes Dick’s opinion of the name “Batmobile,” and even goes so far as to say that maybe, just maybe, Batman “could find some wee benefit from speaking to a person or two, now and then– of course not while you’re so busy punching somebody senseless?”

Hal Jordan, Green Lantern, gives him the treatment on behalf of the Justice League. Wonder Woman wants Batman dead and shown as an example of the cape community policing their own. Superman, showing signs of the ending of Dark Knight Strikes Again decades ahead of time, declares that “this is my world. These are my people. These are my rules.” He overrules her. The only person in the JLA who likes Batman is Plastic Man, who is insane.

The dislike, or grudging acceptance, is nearly unanimous. Vicki Vale dodges a direct meeting with Batman, but calls him a “flying rat.” The only person in the entire book who meets Batman and is anything less than completely unimpressed with him is a woman he rescues from rapist muggers in an alley. She says, “Thank you. I love you,” as Batman is leaving. His monologue: “Nobody loves anybody, my darling. We just survive.”

Think it through. No one in the book likes him. He’s playing a role that is so obvious a recently-traumatized twelve-year old can see through it. He has flashes of darkness, where thoughts of his parents come unbidden to his mind. He repeatedly calls grief the enemy, because grief leads to acceptance and forgiveness. “Grief forgives what can never be forgiven.”

Issue nine. He unleashes Robin on Green Lantern because it’ll be a laugh and he needs to show the JLA he means business. The anger and grief inside Robin spills over and he nearly kills Green Lantern. Batman is suddenly forced to realize that he’s been going about his quest wrong. He was forcing the boy into the steps he followed to become Batman, not realizing that grief and closure are vital to growth. The issue ends with them weeping over the graves of Dick’s parents.

That is the first step toward Batman becoming an actual hero. ASBAR is the story of why Batman needs a Robin. It brings him back down to Earth and forces him to acknowledge his own flaws and humanity. It shows him that you can be young and adjusted, and that crime fighting doesn’t have to be about revenge. The mean one-liners and Eastwood fade. The fun of crime fighting doesn’t. “Striking terror. Best part of the job.”

Of course, the tragedy of ASBAR is that Dark Knight Strikes Again lies in its future. After being fired, Dick Grayson went bad. Batman has to kill him, and while he mocks him, he still marks his passing with a sad, “So long, Boy Wonder.”

Make no mistake: the Batman is a child’s fantasy. Batman’s defining moment is tragedy, and it has effected his adulthood in a way that, say, Spider-Man’s tragedy didn’t. Uncle Ben’s death taught Spider-Man that heroism is a requirement, not an option. The death of Thomas and Martha Wayne taught Bruce that the world is a cruel place. He took Zorro, a character his father enjoyed, and stepped into his boots. It is telling that Miller revises Robin’s origin to include the fact that Dick’s father was a Robin Hood fan and often took Dick to see the movie. Dick chooses his name in honor of his father. Batman does, too. But the difference in the two of them is astounding.

But, for now, ASBAR is the last lesson of the Batman. He’s mastered ways to hurt, maim, kill, investigate, deduce, and solve. This is where he learns to feel. I assume that next year’s Dark Knight: Boy Wonder will wrap the story and show us how Batman and Robin work together in their first bout against the Joker.

All-Star Batman and Robin, the Boy Wonder is grotesque and exaggerated. It’s not a satire, and there’s definitely a point to all of the glorious excess.