Frank Miller Owns Batman: “i mean, i’ve seen better, but i guess this is okay.”

July 18th, 2011 Posted by david brothersI like Captain Marvel because he’s a boy’s fantasy. Say a magic word and bam, you turn into an idealized version of yourself, people respect you and take you seriously, and you’re a true blue hero.

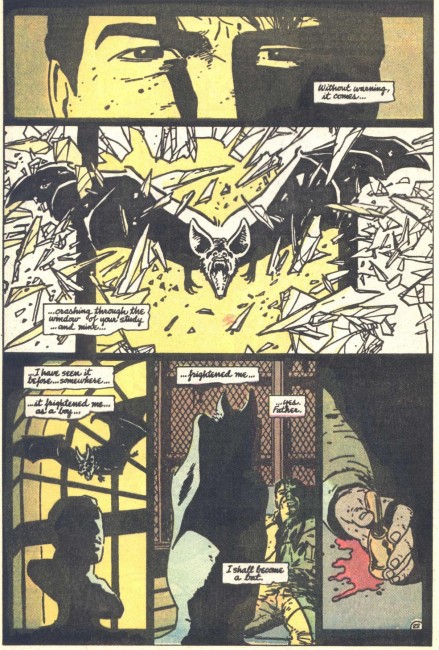

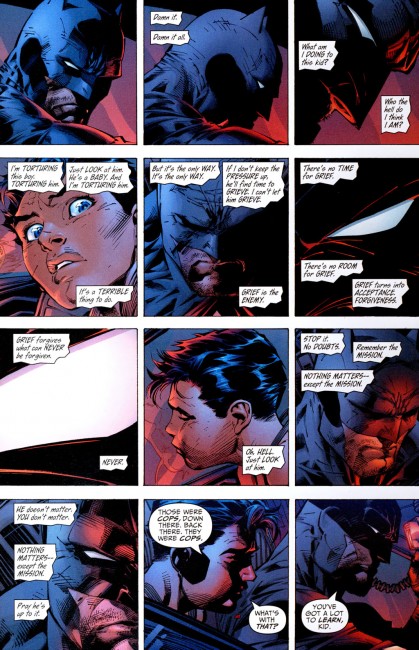

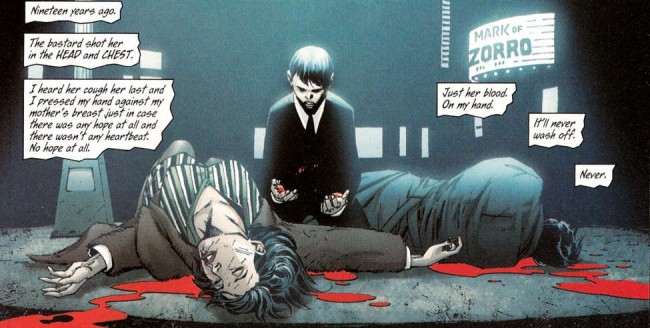

Batman is a child’s fantasy, too, but a more specific one. It is Bruce Wayne‘s fantasy, and his reaction to the death of his parents. The actual Bat part of the fantasy came later, of course, but the avenging angel saving the innocent from the predations of criminals was born as Bruce watched his parents die.

It’s kind of a childish, or maybe just simple, idea, isn’t it? Batman declared war on crime. Not a specific type of crime, or a certain criminal. He declared war on a nebulous object, something so big that it will never, ever go away. Why? Because it hurt him and took his parents away.

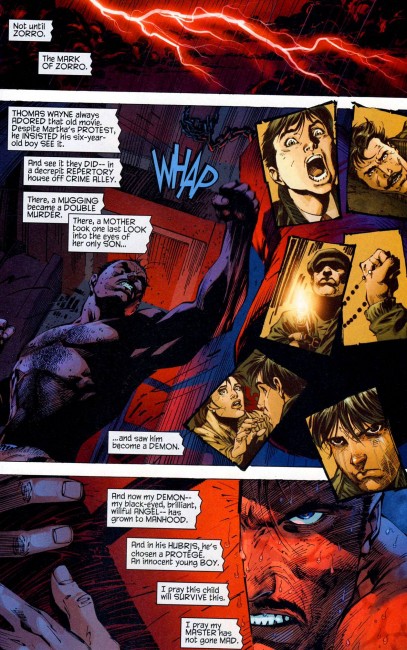

I like how the Mark of Zorro figures into Batman’s origin. It was his father’s favorite movie, and it was the very last thing he did with his family before he died. The Mark of Zorro is the last thing he saw as an innocent, and that’s significant. Don Diego was a man who believed in justice and protecting the downtrodden by night, and pretended to be an affable fop by day. He used a certain symbol as a calling card and to strike fear into the hearts of his enemies. A Z scratched into flesh or cloth was a warning and an admonishment. It’s easy to see why this would be attractive to a six year old kid who just watched his parents die. It’s simple and attractive, with a very clear idea of right and wrong.

Bruce Wayne then dedicates his life and fortune to training himself in the arts of crime fighting and fighting. You can probably assume that he’s an expert fencer, too. He returns to Gotham as a twenty-five year old and attempts to begin his war on crime, but soon realizes that it won’t work without a symbol. The genre demands drama, and a bat comes out of the nighttime sky and pushes its way into his life and psyche. With the addition of that symbol, he’s ready to begin his war.

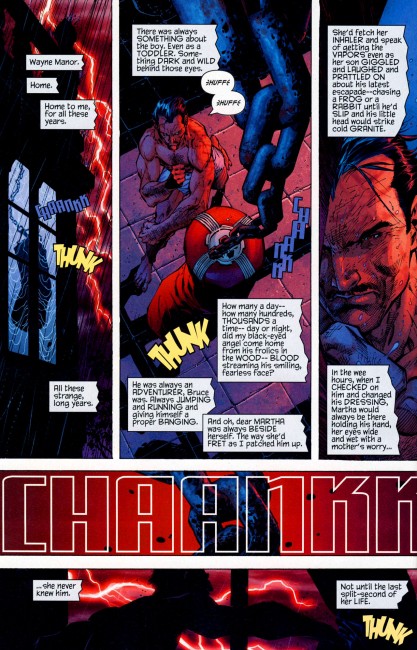

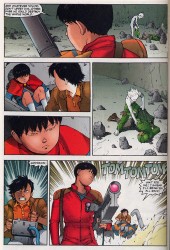

One of the best bits in All-Star Batman and Robin the Boy Wonder is the huge fold-out spread of the Batcave. It’s spectacle on overdrive, the sort of thing that only comic books can do, and it’s wonderful. It’s the first time I’ve really seen the Batcave as something incredible, rather than being Batman’s dark, nasty cave. It’s filled with stuff. He’s got a gang of cars in various styles. There are suits of armor that sit in homage to some of the best-respected armies in history–Greek hoplites (presumably Spartan?), Roman Centurions, Japanese samurai, and a Crusades-era Muslim soldier. There are helicopters and jets.

And then, big as life, there’s a giant robot tyrannosaurus rex in the process of being built. This isn’t an arsenal. It’s a toy chest. Every single thing in the Batcave can be mapped to a real-life toy, save for maybe the Bat-computer. The Batmobiles are essentially Hot Wheels in a variety of styles, and the suits of armor are soldier toys, something that would let you make cowboys fight aliens or knights fight tanks. All he’s missing is a giant robotic GI Joe. The cave’s a giant playset.

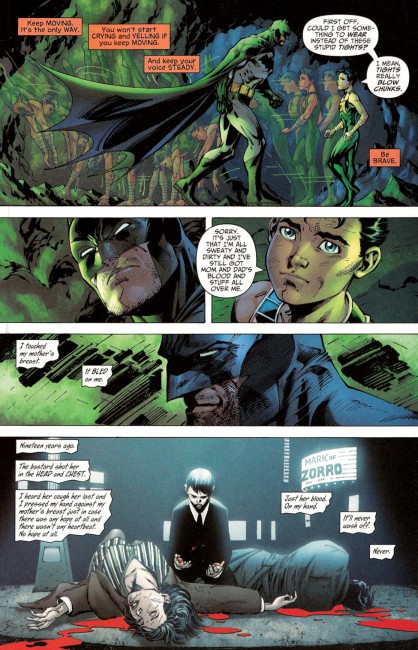

And Batman, who is twenty-five years old, turns to Dick Grayson, age twelve, and sees the look of pure and utter astonishment on his face and asks him if his cave is “cool or what?”

“Eh, it’s aight.”

:negativeman:

Batman: child at heart. I hesitate to call it arrested development because it isn’t, really. It’s a sort of parallel development. He found his calling decades before any of us actually do. It just so happens that his calling springs from a very, very childlike space, and he’s got the money to do exactly what he wants. He can fulfill almost every childhood dream, but most especially the crime fighting one, and he does that by way of his wonderful toys.

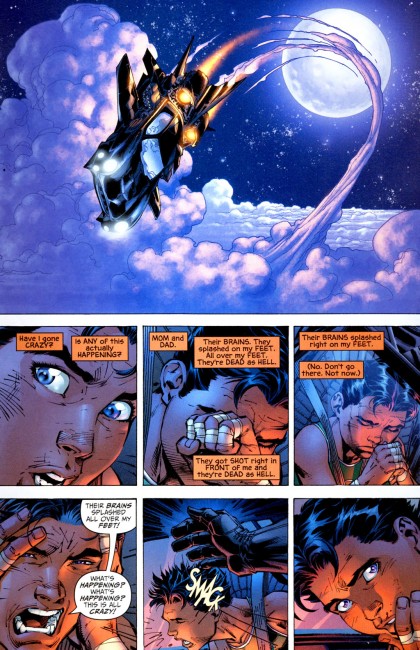

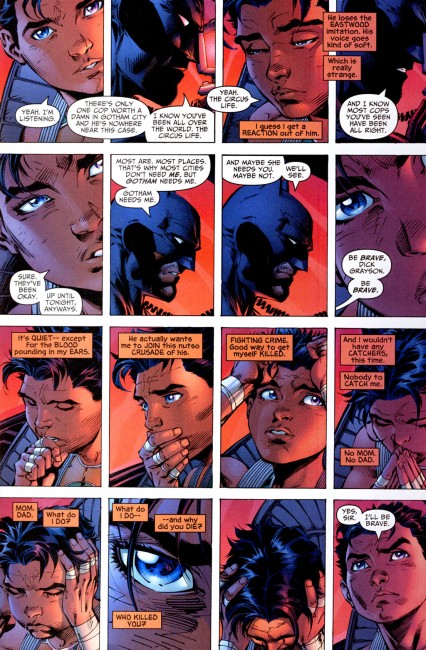

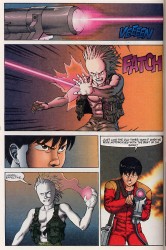

Miller and Lee reveal similar origins for Robin. While exploring the cave, he finds Bruce’s cabinet full of weapons, picks up a bow and arrow, tests the tension on the string, closes his eyes, and thinks. The picture that comes to mind is Errol Flynn as Robin Hood on a moonlit night. Robin Hood, of course, is one of the precious few characters more swashbucklin’ than Zorro.

Sidebar: I really like Lee’s storytelling on this page. Panel two, with him looking at the bow leads nicely into panel three, with the “…” implying thought, and then the angle of Grayson’s head lines up with the angle of Robin Hood’s head, as if he’s becoming the character.

When Grayson explains why he’s going to be called Hood to Batman, he mentions that his father used to make him watch an old movie about Robin Hood, and that that’s why he took up archery. So, once again, you have the son attempting to honor the father through deeds and identity. Both characters latched onto something from their childhood, something that is an indelible link to their parents, and made it the focal point of their life.

At first, I thought this was just sort of a nice coincidence, right? “I do this in remembrance of you” sort of thing. But, no: the costumes and gimmicks are a reminder of their parents. Every time Batman goes out and slings a Batarang, or every time Bruce Wayne guzzles ginger ale like it’s champagne, he’s connecting himself to his folks by way of The Mark of Zorro. Every single time he suits up, that’s what he does. Robin, too. When he flips down from a skylight, leading with a joke and following that with a closed fist–that’s The Adventures of Robin Hood. That’s his father. That’s his family. The costumes and identities are like… tokens, or keepsakes. A reminder, a crystalized memory.

Batman and Robin are living memorials, a testament to their love for their family.

(Funny, but unrelated, trivia: Basil Rathbone was in both The Mark of Zorro and The Adventures of Robin Hood, playing opposite Tyrone Power and Errol Flynn, respectively. Batman and Robin/Zorro and Robin Hood have the same enemy, it seems.)

next: every inch of me is alive.