–For my money, the best superhero was invented back in 1962 by Stan Lee & Steve Ditko. Peter Parker, Spider-Man, is as close to perfect a concept as you’ll find for a superhero. On a most basic, “who is this guy?” level, Superman is defined by his innate God-like goodness. He’s Moses writ even larger, sketched out on a cosmic level. Captain America, too, has that same innate goodness. Batman is defined by his anger at one very bad day. Hal Jordan as Green Lantern is a man in an occupation. Wonder Woman is heir to a lineage of, if not outright heroism or adventuring, then at least mythological significance.

Spider-Man, though, is defined by his imperfect humanity. He got powers, went for the quick thrill, and his own arrogance led to him paying an agonizing price. His heroism since then is due to guilt and finally recognizing what it is that he was meant to do. “With great power comes great responsibility” isn’t just a pithy saying. It’s the Golden Rule and a positive way to live your life. If you have the ability to do something, then you should. It’s that easy. It’s that hard.

As a character, I feel like Spidey is one of the precious few genuinely inspirational superheroes out there. Too many of them are perfectly formed and flawless. Superman preaches being good and Batman preaches being good by doing the hard thing. Spider-Man tells you to be good, but also allows for the fact that you can, and will, screw up. Those screw-ups may be catastrophic, but you will recover and life goes on. Spider-Man would not exist without Peter Parker being a selfish human being.

–Kaare Andrews wrote and drew Spider-Man: Reign, a four-chapter comic book about the end of Spider-Man. José Villarubia colored it. The art hasn’t aged as well as I hoped over the past few years — the 3D CG work looks a little too obvious, mainly — but it’s still as good as I remembered. It’s one of my favorite Spider-Man stories, and to be perfectly real, the last two chapters hit me about as hard as Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely’s We3 or Joe Kelly and JM Ken Niimura’s I Kill Giants

or Joe Kelly and JM Ken Niimura’s I Kill Giants . It’s not for reading on public transportation, if you’re at all attached to these characters.

. It’s not for reading on public transportation, if you’re at all attached to these characters.

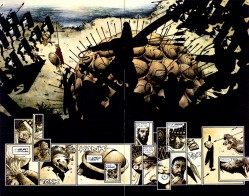

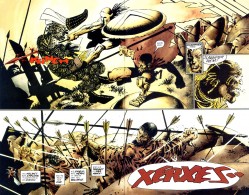

–Reign is an explicit homage to Frank Miller, Klaus Janson, and Lynn Varley’s Batman: The Dark Knight Returns . There are newscasters named Miller Janson and Varr Magnuson (or Jones–it changes), for one thing, and there are several other parallels that hammer the homage home.

. There are newscasters named Miller Janson and Varr Magnuson (or Jones–it changes), for one thing, and there are several other parallels that hammer the homage home.

DKR is interesting, because I think it’s a story that has near-universal appeal. It’s a story about one last job, for one thing. It’s about a man coming out of retirement to do something only he can do. It’s about coping with old age. It’s about respect and revolution and paranoia and Ronald Reagan. There’s a lot to like about it, and what I like the most is probably that it’s about the fact that everyone has something they are good at, something only they can do or are led to do. When you aren’t doing that thing, when you’re avoiding it, you are less than you should be. There’s this line about how the rain on Bruce Wayne’s bat-emblazoned chest is a baptism. Being the Batman is a religious experience for him. It’s not just about fighting crime. It’s about being who he is.

–Spider-Man: Reign is about who Peter Parker really is. When the book opens, he’s old, bearded, and getting fired from a florist. He’s pathetic, and going nowhere. He’s not Spider-Man any more. He’s just an old and tired man. He sees his dead wife when he goes home and sleeps alone. He has no friends. He has no life.

What Reign gets right is that Spider-Man is a role that Peter Parker plays. Peter (and it’s funny that I think of him in my head as “Peter” instead of “Parker,” like he’s an old friend, so please bear with me and my attachment) is an orphan who was raised by his aunt and uncle. He’s meek, awkward, and dorky. He’s not uncool, exactly, so much as not traditionally cool. He’s the kind of person who would grow up to be a regular guy, once he escapes the toxic and fake classifications of high school.

When he’s Spider-Man, though… that’s when he puts on a personality. Spider-Man is funny, exciting, and daring. He’s all the things that Peter Parker believes a hero should be. There are points when Peter is clearly visible beneath the mask, times when his put-on confidence and expertise crumbles under the weight of a cosmic threat, but that only serves to highlight just how human Spider-Man really is under his mask.

Spider-Man is the suit that Peter Parker wears to be a hero. The jokes, the confidence, all of that derives from who Peter is, but it isn’t who Peter is, if you follow. Spider-Man is Peter Parker Plus, a purer, stronger version of his day-to-day life.

–Early on in Reign, at the cusp of Spider-Man’s return, J Jonah Jameson visits Peter Parker. Jonah is excited to see him. He’s a believer now. He knows Peter was Spider-Man. He mentions that Peter seemed immortal to him, that he “thought you’d be twenty forever.” He gives Peter a package. Inside the package is a camera, one of Peter’s old ones from back in the day. Peter’s spider-sense wiggles.

Jonah goes outside and runs afoul of the fascists who police New York City. Peter picks up the camera and drops it, realizing what the fabric the camera is wrapped in really is. Jonah’s become a victim of police brutality. Peter realizes that the fabric has eyes. Reflective eyes. Eyes that show him as old, weak, and beaten. Jonah has been beaten bloody, but begins apologizing. “I’m sorry. So sorry,” he says. “I’m sorry for all of it, my boy. We have so much to talk about.” Page turn. Full spread of an old man wearing a black Spider-Man mask falling out of the sky.

Peter’s captions: “I’m not even there. I’m watching from far away. And all I know is that the mask… the mask thinks it’s funny. It’s laughing. Laughing.”

Meanwhile, Spider-Man dives into battle and cracks wise the whole way down. He mocks the thugs even as he effortlessly takes them apart.

Peter can’t take it. He can’t take the laughter. He turns off the volume and thinks about his past. He thinks about Uncle Ben’s murderer, “a yolk-filled body broken on the ground.” He thinks about the pressures his family put on him. He thinks about Aunt May telling him that he’s her life. (“But I don’t want to be your life.”) He thinks about Mary Jane telling him they’re connected forever, and that he’ll always protect her. (“What if I can’t?”) He thinks about Uncle Ben, the hole in his head still smoking as blood runs down his face like tears.

There’s a tangible difference between Peter Parker and Spider-Man. That difference is what makes Spider-Man so golden. With the mask off, Peter is just a man. With the mask, he’s bigger than anything else.

–Andrews uses masks as motifs throughout the story. Spider-Man is restored to his former glory after Jonah delivers the mask. Masked heroes and villains are dubbed super-terrorists because they go against the order of things. The thugs who police New York look identical, thanks to their masks. The black mask has a different meaning than the red mask. When Kraven kills Spider-Man and takes his trophy, he removes Spider-Man’s mask, not his head. It goes back and forth — order and chaos, chaos and order — but it’s always about freedom.

A child is murdered in chapter two. His name was Kasey, and he was fighting on Jameson’s side. Kasey’s death spurs another, unnamed character into action. She holds up his beanie and realizes that it’s a ski-mask. When the alien invasion hits and everything’s gone south, the girl’s first move is to run to where she knows a lot of people are. She knows that she can’t outrun the aliens… but she can outrun the other people. She didn’t even realize what she was doing as she did it, but she looks back and something changes. She grabs a pipe. She rings a bell. The aliens leave.

“I just needed to do something,” she says. “Anything. Besides running. My shoes — they don’t quite fit anymore. We can’t rely on them any more. The old men. They can’t show us how to live. They took our city and made it a cage. They only hurt us. Stop running. Stop hiding. It’s time we became something more than what we are.” Another kid says that if they at out, then the authorities will hurt them and their families both. The girl looks at the mask and says, “Only if they know who we are. We’ll use masks.”

The old men turned NYC into a cage in the name of protecting everyone. The youth understand that this is completely unacceptable. If they don’t do right by you, you take it, by any means necessary.

–Spider-Man, as a story, is universal. We can all relate to him, one way or another. A side effect of being universal is that it’s also open to reinterpretation. Kyle Rayner, Green Lantern, is very much in the Spider-Man mold. So are Richard “Nova” Rider, Virgil “Static” Hawkins, Miles Morales, and plenty more heroes. Each reinvention, assuming the quality is there, reveals another aspect of Spider-Man and shows just how far that concept can be stretched before it breaks. At the root of Spider-Man is us, and us includes 7 billion people. There’s a lot of wiggle room there.

The girl is the Carrie Kelly of Reign. She provides a hard dose of morality to the story, despite doing nothing more than witnessing Spider-Man in action. She stands up against men twice her age or more, armed with just a bell and her voice. When she runs into Sandman, agent of the Reign and the man in her way, it turns out she’s got a lot to say.

Let me tell you a thing about hope! Hope has three daughters: Anger at the state things have fallen into. Courage to fight to make things right. And the third daughter is truth. And she won’t hide her true face any longer.

Sandman watches her preach. His throat goes dry, “even for sand.” The girl has his eyes. She turns to stone right before his eyes and says “Nice to meet you.” She’s stronger than he is. Sandman says that she’s “more like cement than sand.” When the soldiers open fire, she stands there and takes it.

This is Spider-Man. Anger, at his failure to protect his uncle. Courage, to go out and make sure it never happens to anyone else. And truth — the idea that heroism is something that you must do, if you are able to do it. Standing tall against tremendous, insurmountable odds, and refusing to move. An unstoppable force breaking against an immovable object. Right versus wrong.

The girl, like Carrie, is carrying on in the name and spirit of the star of the book. Spider-Man as inspiration, both inside the text and out of it.

–Spider-Man is about family. The never-ending battle for Peter Parker is how much time he can spend being a superhero instead of tending to his aunt or girlfriend. How much does Peter have to sacrifice to do this thing he must do?

In Reign, Peter struggles with family. He feels like he let them down. Peter knows what they expect of him, and he knows that he’ll fail them. Everyone died. The radioactivity in his body poisoned his wife. He failed his uncle. His aunt still died. His family wanted him to be one thing, but he couldn’t do it. He failed. Time took its toll.

On Mary Jane’s deathbed, he spends some time reminiscing about their time together. “I remember the day we met,” he says to her silent form. “The electricity tingled down my neck. You already knew it and you told me. I hit the jackpot.” He goes on and on. “My chest was too small for what you did to my heart.” “I wanted to tell you so much, but words didn’t have enough… so I tried to show you.” Bu his radioactivity is killing her, and the last thing he hears her say is “Go.” He leaves the room, off to stop another crime, and she dies while he’s out. He comes back to an empty room.

He’s in the middle of a horrific encounter with MJ’s corpse as this goes on. He spills his regrets and tears. “I once said that I’d sooner rip out my still-beating heart from my own chest before I ever hurt you. I’m a liar.”

MJ’s corpse, being pulled along by Doc Ock’s tentacles, says “Stop being silly. That last day… you never let me finish. I tried to tell you, ‘Go… go get ’em, Tiger.'”

(This is the part that murders me every time.)

This is why Spider-Man is about family. You think you’re a failure. You think you can’t live up to the expectations of others. You think that you should have been able to protect them, even when things beyond your control prove otherwise. You internalize all of this guilt and horror and self-loathing… and forget that your family is there for you, no matter what. Love is way deeper than that. On her deathbed, Mary Jane wanted Peter Parker to go do what he does. She wanted him to be Spider-Man, and all he felt was guilt over being Spider-Man. He didn’t understand that she loved all of him, Peter and Spidey both, and that he didn’t fail her at all. He became exactly what she wanted him to be. He was the man she loved, up until her dying moment.

–Peter Parker buried his red & blues in Mary Jane’s coffin. It’s blatantly symbolic. His love died and so did his drive, blah blah blah. More than that, though, is the fact that that action equates Spider-Man and Mary Jane. The two are irrevocably linked. Now, he’s Spider-Man because of her, rather than Ben. She saw the best of him. It actually reminds me of something from El-P’s “TOJ”:

Everything you said, I took it all to heart

And you spurred a change in me

Before I could become a new sun, I had to fall apart

And I can see that now, and I wish you well

‘Cause you saw what was good in me

And I’ll be God damned if I didn’t see that myself

If you want to summarize Peter and MJ’s relationship, that’s it right there. Mary Jane is a rider. She makes him better simply by believing in him, and in making him better, she makes the world a better place. Everything has a point. Everything happens for a reason.

Spider-Man lost sight of the truth, and was lost for decades.

Even as a hallucination, Mary Jane knows the truth. I love the sequence where Mary Jane smiles shortly before something forces Spider-Man into action. She’s driving the car when Spidey hallucinates, too. You can see her fabulous red hair behind the wheel. She knows the truth. He never remembers putting on the mask, but the outcome is always the same. “Woo-hoo!”

–Spider-Man is such a perfect hero because his relationship with his villains is so personal. Spidey’s best villain is undoubtedly Harry Osborn as the Green Goblin, a best friend turned enemy. But for some reason, he has intensely complicated relationships with all his major villains.

I don’t mean Batman/Catwoman complicated, either. That’s the kind of complication that derives from cheap wish fulfillment and lazy writing. Plus, Spider-Man and Black Cat’s relationship is infinitely more interesting. I’m talking Norman Osborn complicated, where one of his worst villains is also a corrupted father figure. Doctor Octopus complicated, where the older man is bent on proving himself to the younger man or obsessed with their status as children of the atomic age. Lizard complicated, where a beast erupts from a kind man who wants the best for his family. Sandman complicated, where the villain becomes a hero after being shown a better way. Morbius, Prowler, Vulture, Chameleon, Kraven, Electro, Rhino, and more — Spider-Man has been fighting these dudes since he was fifteen years old, and they have actual relationships beyond the punching and kicking. They can sit and talk as easily as they can throw a punch, and often have.

This is true in Reign, too. The Sinner Six — Kraven, Sandman, Electro, Hydro-Man, Mysterio, and Scorpion — are released from prison and sent after Spider-Man. They all have grudges to settle with Spidey. Jonah comes to Spidey because of their history. Venom is the prime mover behind the alien invasion, and it’s doing it in part because of their past together. Recognizing the truth of his relationship with MJ made him put the tights back on.

With Spider-Man, it always comes back to relationships, healthy or otherwise.

–Andrews makes a big deal out of people watching what’s going on. There’s a newscast that runs throughout the series. Jonah hacks everything with a screen and livestreams Spider-Man’s fight. Families gather around TVs and mothers cover their children’s eyes and everyone watches. In watching, they learn. In learning, they realize that they have no choice: they must act. They fight back against the Reign. They protect each other. They save each other. They lift each other up. Spider-Man is a role model. The girl sees Spider-Man and realizes that he’s just an old man. “Weak. Like the rest of us.”

But if an old man is willing to fight for what he believes in, what excuse do you have?

Spider-Man watches, too. He loses a fight when he realizes that Kasey has been killed. He watches what people do around him. And then he acts. The things he sees require him to act. He has the power, so he has the responsibility.

–Spider-Man’s got jokes. This is one of the most important parts of the character. He isn’t a stand-up comedian, or even particularly good at telling jokes. He’s just got a quick wit and a mouth that runs faster than he can think. He’s talky, he’s jokey, and he just won’t shut up. Andrews nails this aspect of the character.

Even when an aged Peter is old and morose, Spidey comes out of the gate with jokes, stunts, and flips. He’s a showman. It doesn’t really matter whether the jokes are a cover for fear or whatever. What matters is that they exist. They put him and the people he’s rescuing at ease. They break down the walls of aggression between him and his enemies, replacing it instead with mocking humor or genuine emotion. Peter remarks again and again that the mask is laughing, and that’s true. You can’t have a deadly serious Spider-Man but once or twice.

I wrote about a ’90s Spider-Man story where just that happened in 2006. I called it “No Laughing Matters,” a better title than I usually come up with. Spider-Man not laughing in that story mattered because it was a sign that Spider-Man was wrong. Spider-Man isn’t Batman. You can’t graft the most unpleasant parts of Batman onto Spider-Man and still expect to have Spidey.

I like how many aspects of that story are reflected in Andrews’s Reign. I hadn’t considered them in relation to each other before now, but they fit together like puzzle pieces. Shrieking is the type of story that benefits from the contrast between the Spidey we know and love and a darker, meaner version. “I am the Spider!” works once, and just once, because we all know that the Spider is actually the guy with a joke and a wry smile on his lips. That’s where these stories fall short.

Andrews doesn’t overdo it with the jokes. He uses them to great effect. Spidey tells Mysterio to never dress like a man’s dead wife… unless he pays you to. Spidey sings The Ramones once he puts the red and blues back on. He tells a knock-knock joke before he storms the tower with the end boss in it. He handles the big Electro and Hydro-Man team-up with ease. Scorpion tells Spidey that he can do anything with his new duds. Spider-Man says, “Can you fly?” as he kicks him out of a window. He tells a joke as he’s being beaten to death by aliens. And it all feels so right, so Spider-Man. Put him in dire straits and he’ll go to hell with a grin on his lips and a joke in the air.

–Amazing Spider-Man 316 was my first comic. I can’t believe I don’t have it memorized. I think I still have it kicking around my apartment somewhere. It was a David Michelinie and Todd McFarlane joint , and they hooked me. I loved, and still love, how McFarlane drew Spidey’s webs and the creepy positions McFarlane put him in. I liked Michelinie’s soap opera script. I got lucky and managed to talk somebody into giving me that first Amazing Spider-Man Masterworks as a gift as a kid, and that let me go back to the Lee/Ditko

, and they hooked me. I loved, and still love, how McFarlane drew Spidey’s webs and the creepy positions McFarlane put him in. I liked Michelinie’s soap opera script. I got lucky and managed to talk somebody into giving me that first Amazing Spider-Man Masterworks as a gift as a kid, and that let me go back to the Lee/Ditko source. I was a regular reader of the Spider-Man newspaper strip during the ’90s, when Alex Saviuk was drawing it. Later, when I got older, I got to experience the Romita/Conway/Andru

source. I was a regular reader of the Spider-Man newspaper strip during the ’90s, when Alex Saviuk was drawing it. Later, when I got older, I got to experience the Romita/Conway/Andru years and JMS and JRjr’s run

years and JMS and JRjr’s run was waiting for me when I came back to comics. The first 130 or 140 issues of Amazing Spider-Man are some of my favorite comics ever, even over and above the Lee/Kirby Fantastic Four

was waiting for me when I came back to comics. The first 130 or 140 issues of Amazing Spider-Man are some of my favorite comics ever, even over and above the Lee/Kirby Fantastic Four that everyone else thinks are the best. How could you not love those stories? Peter Parker grew up, met girls, went to college, and got on with his life. They’re beautiful.

that everyone else thinks are the best. How could you not love those stories? Peter Parker grew up, met girls, went to college, and got on with his life. They’re beautiful.

Spider-Man is that one guy who made comics for me, above and beyond any other character. The guys who shepherded him over the past fifty years have had a huge effect on my taste in comics art and writing. The character they’ve created is one I’ve fallen in love with slowly. I didn’t even know it happened until it did, really. I probably thought to myself “Spider-Man is the best hero” and then realized it was true. A couple of his spinoffs and variations, most notably Static, are super important to me. I’m not a characters over creators guy at all, but he’s still a character I’ll check in on, just to see what’s new in his life.

I’m glad that Andrews and Villarubia did Spider-Man: Reign. It’s a book aimed directly at the heart of a Spider-fan like me, a guy who grew up with this schmuck who rocks red and blue and tells bad jokes. It feels like it was written for me, because it hits so many of the things I love about Spider-Man.

You can buy it on Comixology for eight bucks, total or on Amazon for twelve . I think it’s worth reading, if you like this guy like I like this guy. It’s a nice farewell to an old friend.

. I think it’s worth reading, if you like this guy like I like this guy. It’s a nice farewell to an old friend.

, color by Lynn Varley:

is my favorite. Here’s one of them, though.