Frank Miller Owns Batman: “i rushed it. i blew it.”

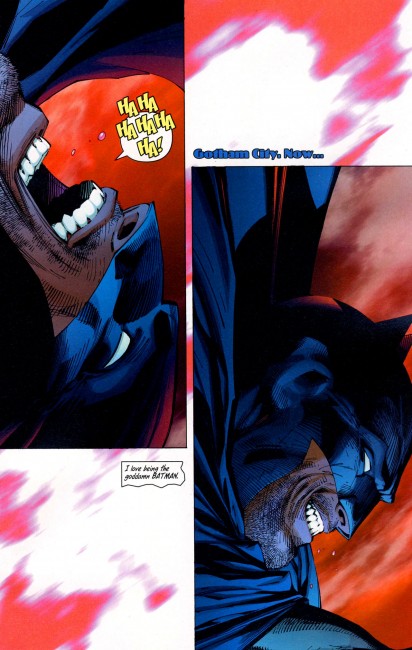

August 8th, 2011 Posted by david brothersJim Lee and Frank Miller’s All-Star Batman and Robin the Boy Wonder is the best Batman story to come out of DC in years. It’s only rival is probably David Lapham and Ramon Bachs’s Batman: City of Crime.

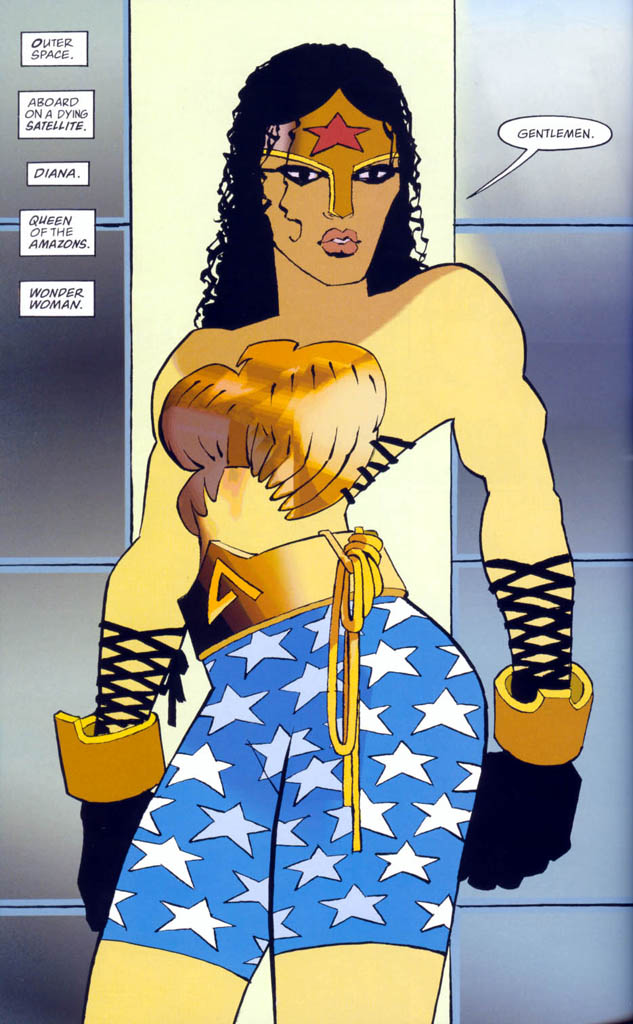

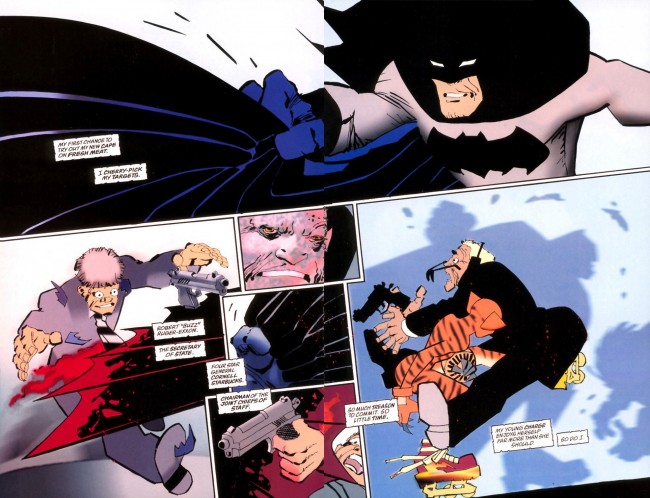

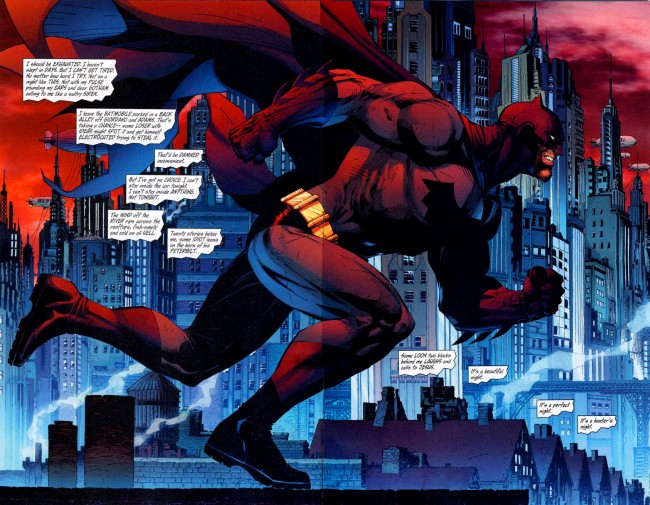

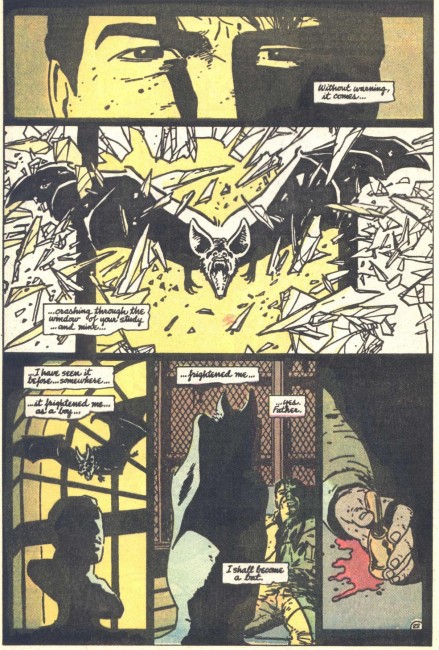

So far, we have most of a Batman. We have the thirst for vengeance that birthed him, the will that powers him, and the rich inheritance that provides his means. Right now, at this moment, we have the makings of an urban legend and a night terror. Cops and criminals both know and fear him, as well they should, and the citizenry knows that there’s a dark angel waiting in the shadows to protect them. The specifics of his mission, and by that I mean the brutal violence, probably aren’t clear to John Q Public, but the fact that he exists and is fighting back is enough. There is someone out there with a spine, and he is on our side.

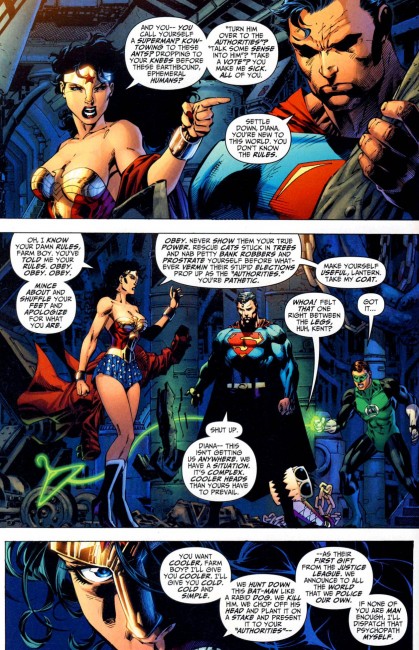

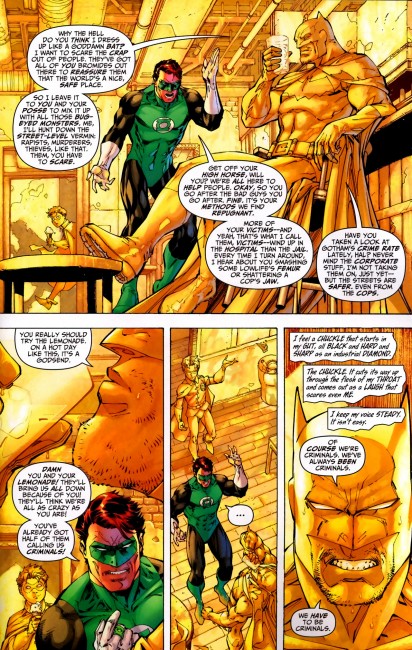

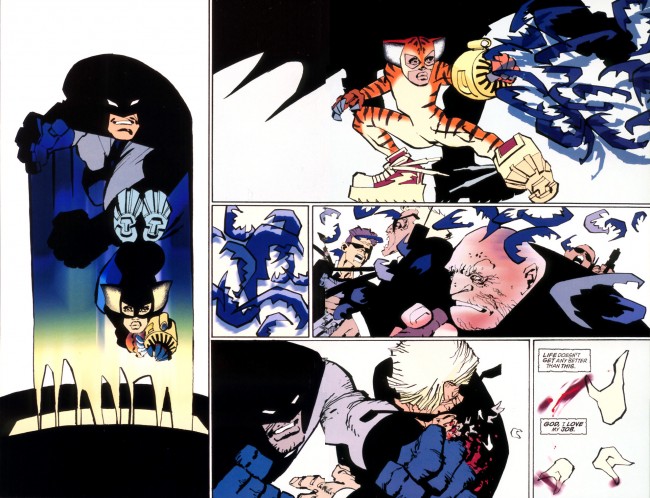

The problem, though, are those specifics. They get the job done, but they’re far from pleasant. They give us a Batman who is a little too hard-edged, a little too happy about getting to do some damage, to be a comic book superhero. The Batman’s methods must be tempered just a little. Right now, he’s a shadow who lurks among shadows. The problem with that is that there’s no difference between one shadow or another. One shadow can hold pain or pleasure, and you won’t know which is which until it’s too late. While it’s clear that the Batman is a benevolent shadow, there’s nothing to suggest that he won’t become one of the other, darker shadows at some point in time.

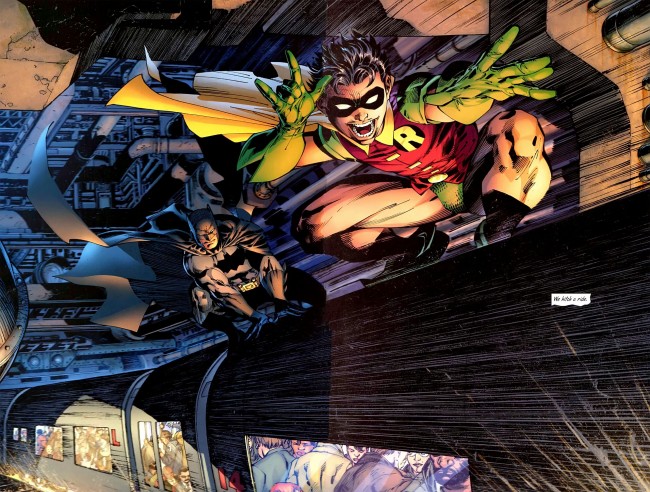

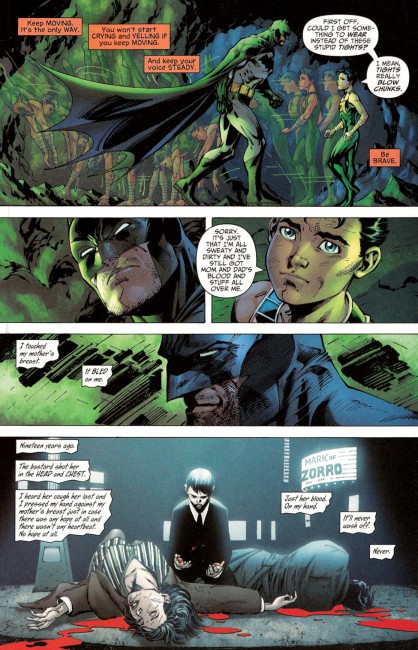

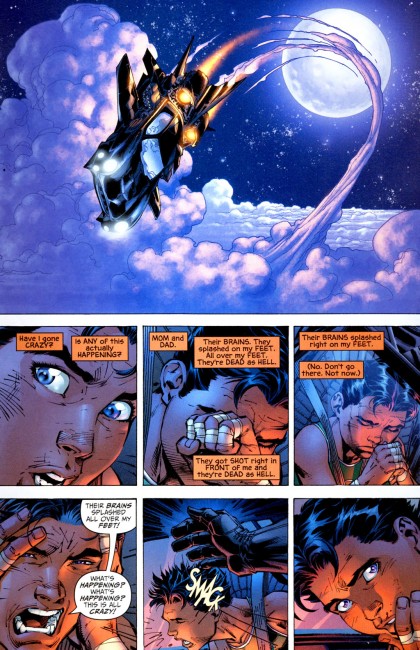

Enter: Robin.

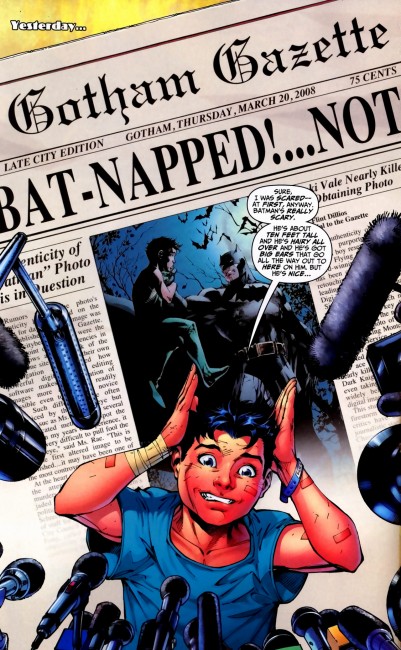

The appeal of Robin is three-fold. He provides a character for young boys to relate to, a fact that is increasingly irrelevant as time goes on. He brightens Batman’s methods, turning him into a four-color hero instead of a bastard child of The Shadow. Finally, he provides a fix for Bruce Wayne, whose development was not stunted as a result of his parents’ murder, but rocketed off in a different direction. We played with toys. He played detective.

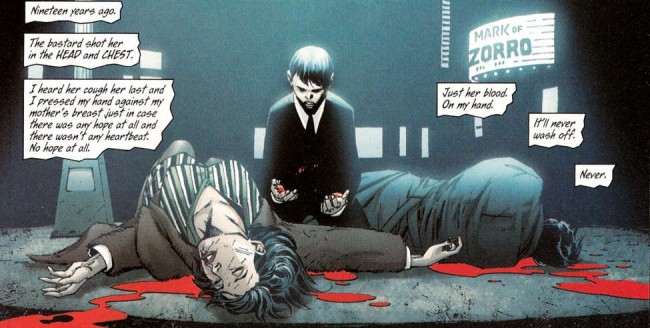

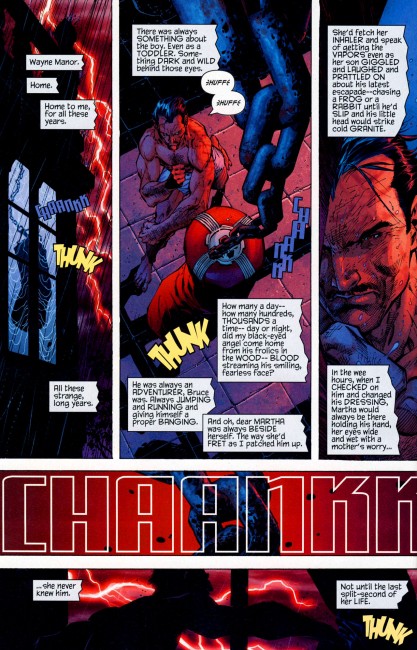

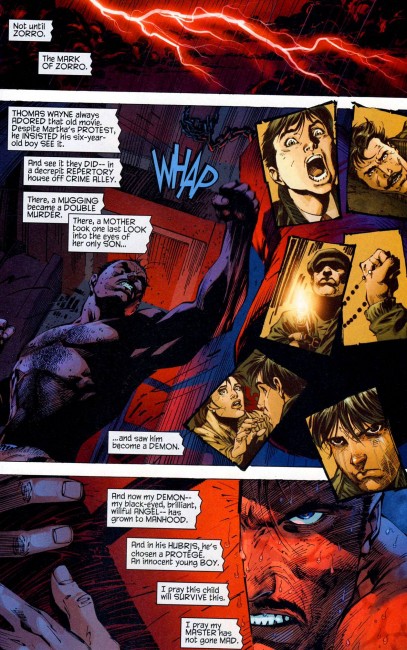

It wasn’t the death of his parents that turned Bruce Wayne antisocial. It was the quest that followed. He wanted to become the greatest detective slash crimefighter ever, and that quest has very little room for proms, high school, and the standard socializing everyone else does. The death of his parents changed how he views the world. Everything is either a tool for his war or irrelevant. This doesn’t preclude Wayne maintaining relationships, but it’s clear that his deepest relationship is Alfred, who was swept up in his quest and has merely managed to hang on for dear life while enabling the child.

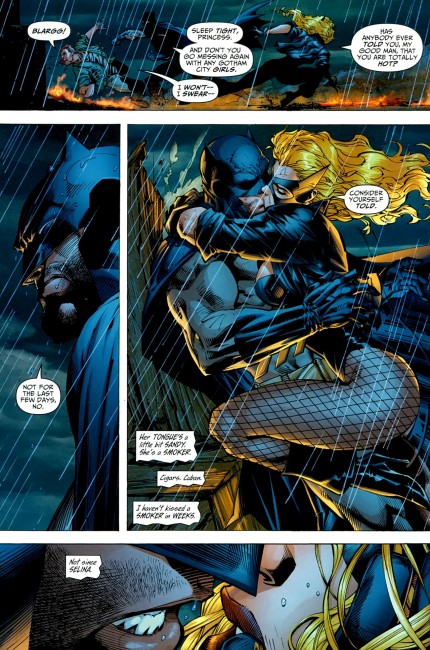

Bruce Wayne grew up, but he didn’t grow up like we did. You can see it in the romantic relationships he pursues as an adult (which generally have built-in trapdoors like “she’s a villain” or “i can never tell her my secret”) or his treatment of Jezebel Jet (where he claims to have turned love into a weapon). He has used a long string of starlets and debutantes as cover for his mission–beards, essentially–without a care for how they would feel about it. They, like everyone else, are tools. WayneCorp, or Enterprises, or whatever, is a tool, too, something that lets him fight his war. Everything is either a weapon, a threat, or not worthy of attention. (More on the subject here, pulling in the idea of a Real Man and examples from Richard Stark’s Parker novels and Lone Wolf & Cub)

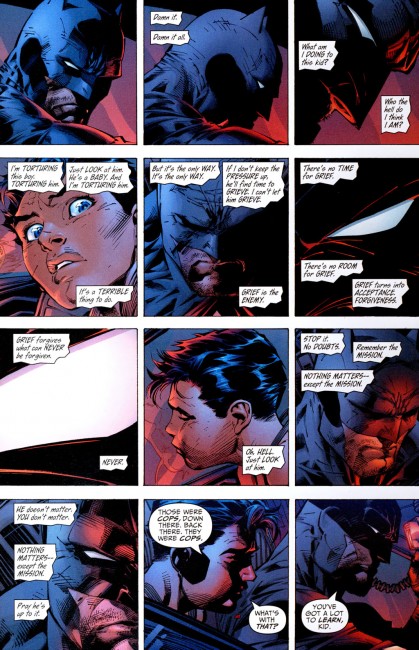

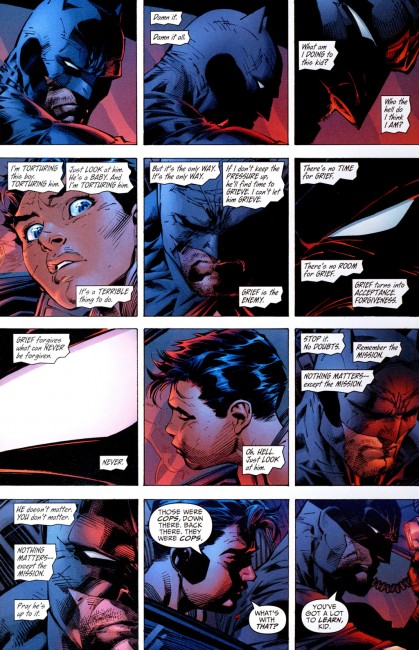

Robin is what changes that. Early in All-Star Batman and Robin the Boy Wonder, Batman refers to grief as “the enemy.” He goes on to say that “there’s no time for grief. There’s no room for grief. Grief turns into acceptance. Forgiveness. Grief forgives what can never be forgiven.” Batman doesn’t think that there’s any room for acceptance in his war. He’s driven by anger at the unfairness of life. If he’d taken time to accept what happened, then he wouldn’t have the edge that has made him so successful. He’s a child lashing out after being hurt. It’s just that his way of lashing out is stretched out over a long period of time than a thrown punch or pitched fit.

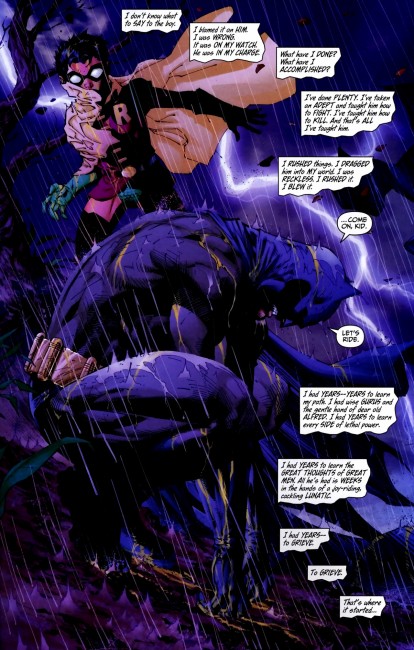

As a result, though, he pushes a twelve year-old kid too far, too soon. If you don’t address these emotions, they’ll rot and fester inside of you. Batman had years to work through his issues, and he did so thanks to Alfred and the dozens of masters he learned his craft from. He didn’t not-grieve–he just grieved in a different way than most people did. He accepted that his parents were gone when he began fighting his war to ensure that no one else’s parents would die that way.

Robin didn’t have that, and nearly killed Green Lantern as a result. The anger and poison was bubbling just below the surface, and when pressed, it spilled over. You have to release negative emotions somehow, and Batman’s mistake was assuming that what worked for him would work for someone else. More than that–Batman’s mistake was thinking that what worked for him actually worked for him.

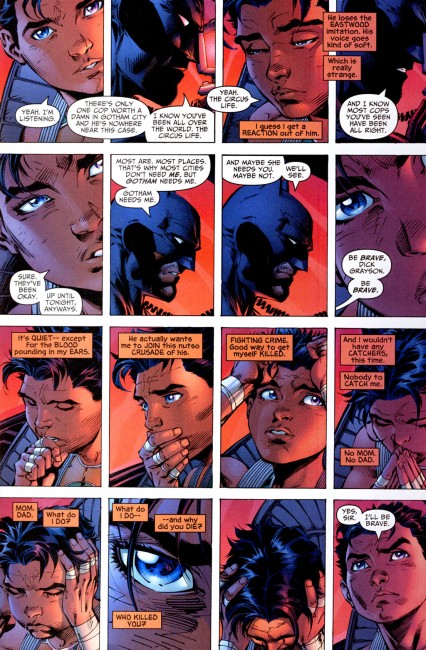

He drives Robin to his parents’ grave and tells him, “Find them. Say goodbye.” Put differently: “Grieve.” Robin hits the gravestone, a symbol of his dead parents, and collapses. Batman’s hand drops on his shoulder and they both cry in the rain, next to Robin’s parents. “We mourn lives lost,” Batman’s monologue says, “including our own.” They’re damned, or maybe just lost, and there’s no going back from here.

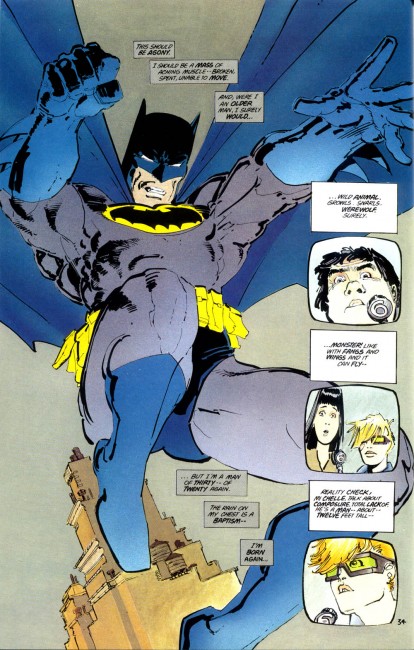

This is the moment when Bruce Wayne turns from the Bat-man, a fearsome creature of the night, to Batman, a superhero with a cheerful kid sidekick. This forces Batman into the role of nurturer, as well as avenger. He can’t proceed along his path any more. It may not be self-destructive, but it is definitely damaging to a third part that’s as close as Robin. He has to change, he has to adjust, because otherwise he damned this child for nothing.

(this is one of my favorite batman scenes, i think.)

Batman is an homage to Thomas Wayne. Batman and Robin, or maybe just Batman’s treatment of Robin from here on out, is an homage to Martha Wayne. Batman has to become a father, instead of just a Dark Knight, and that means that his mother’s mercy is going to play a bigger and bigger part in his life. It shifts his quest from pure vengeance into something more. It’s a splash of love, a love that he’d been keeping at a distance to keep his sword sharp, in a war that sorely needed it. “The greatest of these is love,” right? Robin pulls Batman out of the shell he’d built around himself and into normal humanity.

Robin is the secret to building a better Batman.