Sean Witzke on Ronin? Please and thank you! Chad Nevett on The Big Fat Kill, my favorite yarn? Yeah, I’ll read that! Booze, Broads, & Bullets week continues apace! Dig into the index if you’re new around here and need to get caught up.

With Dark Knight Returns and Year One, Frank Miller left what turned out to be an indelible mark on the character. He made Batman his own in a way that, say, Neal Adams or Jim Aparo, both incredible artists, didn’t. Two short works injected his vision of what Batman is, was, and how he came to be into the minds of comics fans, and that’s been his corner of the universe ever since. He’s only gone back to that well precious few times, with a cover for Batman: Black & White, a brief entry in Evan Dorkin’s World’s Funnest one-shot, a pinup in an anniversary issue or two, and All-Star Batman & Robin the Boy Wonder. Save for the latter book, there is nothing of length, nothing of note. With one exception: Spawn-Batman, a 1994 collaboration with Todd McFarlane.

It’s easy to organize the Miller universe.

Year One kicks it off,

ASBAR is the tale of Batman becoming a human being,

Dark Knight Returns is his return to form, and

Dark Knight Strikes Again is his settling into a brand new role in a new world.

Spawn-Batman fits comfortably between

Year One and

ASBAR, with a Batman that’s good at what he does, but insufferable while he does it. He hasn’t gone through the humanizing process that Dick Grayson is going to push him through, so he’s cold, arrogant, and a blowhard.

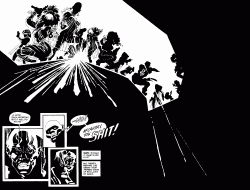

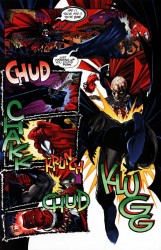

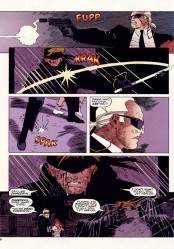

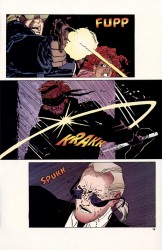

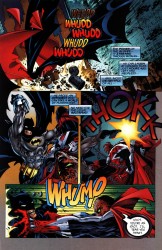

This is about as good as McFarlane’s art has ever looked. It’s cartoonier than I remember his early Spawn work being, with a Batman that’s all shadow and angles and a Spawn that’s all cape. It’s a fairly standard early Image book for the most part, with pages that lean more toward pinups than, y’know, actual storytelling. It’s plenty entertaining, though, and McFarlane fits the bill.

Miller’s story is where all the fun is, though. He’s coming on Claremont-wordy this time, with Tom Orzechowski stuffing captions, sound effects, arrows, and word balloons all over the page. The captions begin as your usual omniscient third-person narrator, but then partway through the book they shift to Jeph Loeb-style dueling thought captions. He’s got a lot to say.

Which is fitting, considering that this book is all the way turned up. The first page has nineteen captions, most with 2-3 words, setting the stage for the book. At first glance, this is Miller at his worst– overly serious, hammering the point home again and again, and aping the wordiest man in comics. But, no, keep reading and you’ll find that isn’t true. It’s wordy, wordier than any comic has a right to be, really, but Miller is having fun here.

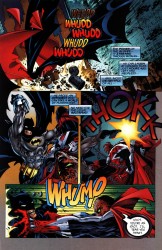

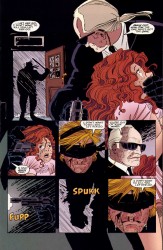

His Batman is impossibly gruff. At one point, he orders Alfred to patch up his shoulder because “the blood’s getting in my way.” Alfred spends the scene urging Batman to drink some chamomile tea. He says that it “is sure to prevent nightmares. Even the self-inflictedvariety.” Batman’s response? “I don’t get nightmares. I give them.”

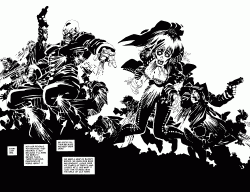

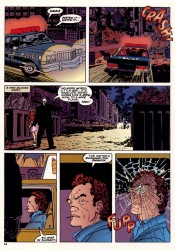

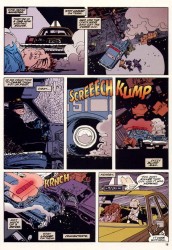

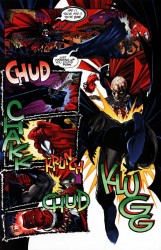

The rest of the story is enjoyably over the top. He and Spawn get into the traditional meet-and-fight that forms the crux of 90% of these crossovers, and Batman takes genuine pleasure in the violence. When he realizes that Spawn is superhuman, he thinks “No reason to be nice” and turns up the violence again. Every third word out of his mouth is punk, and while he tells Spawn to “count your blessings I let you off so easy,” it’s clear that Batman was severely out of his league. He only gets away after dosing Spawn with nerve gas, causing him to vomit.

This isn’t the hyper-competent Grant Morrison Batman, the one with plans for plans and a hairy chest. No, this is your picture perfect Frank Miller Hero: Beaten bloody and senseless, completely out of his league, but with guts for days. A few bandages, a couple splints, and he’s ready to get into it with Spawn again. Having a power glove helps, of course– he lays into Spawn with renewed vigor in their rematch, and the dialogue goes monosyllabic on both parts.

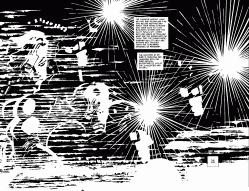

“Idiot. You’re an idiot. I’ll tear you apart.” “In your dreams.” “Break you in half. I’ll break you in half.” “Sloppy. Stupid fighter. No discipline.” “Talking trash. You’re talking trash. It won’t help you.” “No discipline. Stupid fighter. Stupid punk.” “Had it. You’ve had it. You’re done.” “Just warming up you stupid punk.”

It turns into an orgy of sound effects, Orzechowski laying them out Adam West-style, until they trade five (five!) sound effects at once and collapse. They pause to catch their breath and continue their repartee.

“Give it up, punk. You’re finished. Just look at you. You’re finished.” “Look at

you. You can’t even get

up.

You’re the one who’s finished.

khoff.” “I’ll rip you to

pieces Undisciplined

slob.

khagg” “Catch my breath. Just catch my breath and I’ll break you in half.

kheff”

And then robots come and beat Batman basically to death, forcing Spawn to save his life with a little hellfire. While bleeding to death, shaking in the grime of an alley, Batman is still going. “Magic tricks. No way to fight. No discipline. hukkk” Spawn saves his life again, forcing a bit of a mind-meld, and Batman’s response? “If there’s one thing I can’t stand, it’s a dead punk that won’t shut up. We’ve got work to do. Let’s go.”

For about ten or fifteen years, Batman was a douchebag. He was rude to his friends, mean to his family, and everyone sat there and took it because he was Batman and Batman was right. This book, and ASBAR, show you what it looks like when Batman is a douchebag to people who won’t take any of his crap. Batman and Spawn fight like cats and dogs even when infiltrating the stronghold of the bad guy. At one point, Batman says that Spawn is even dumber than Clark. “Who’s Clark?” Spawn asks. “None of your business.” Later still: “Just smash cyborgs and shut up. I’ll do the thinking here.”

There’s your Alpha Male Plus.

(For the record, the villain is Margaret Love, a mad scientist who Al Simmons knows of old. She’s gone completely genocidal and appears on seven pages of the book. She’s alive for five of them, looking death in the eye on the sixth, and launching a missile on the seventh. She isn’t the point of the book. She’s just there to facilitate the fight-and-team-up formula of crossover books.)

Spawn-Batman

Spawn-Batman isn’t an essential piece of the Dark Knight Universe, but it is a fascinating one. It reads like a rough draft for

ASBAR, with its sense of scale all thrown out of whack and pumped full of testosterone. I remember reading in an interview, one that I of course cannot find right now, that Frank Miller has said that you wouldn’t want to be Batman’s friend. It makes sense- considering his mission, his trauma, and the way he’s basically a pulp character gone superheroic, I don’t think that he should ever be Mr. Sunshine and Light. He has to play a role, a role that Alfred sees right through, by the way. Batman has to be the guy lurking in the darkness, laying in wait to pop a mugger’s spine entirely out of place. He’s mean, and he has to be mean, because that’s what his city requires.

At least, until Robin arrives. We’ll talk that out on Saturday, though. Miller’s doing something interesting with Batman, and it only really became clear in ASBAR.

Spawn-Batman, though? It takes itself just seriously enough that both characters are recognizable, but not so seriously that you’re beaten over the head with the import of the situation. It’s stupid. It’s very entertaining.