Tucker kicked it off, I followed up, and then Tucker went and raised the stakes again. I’m wrapping up the story of Don McGregor and Billy Graham’s Panther’s Rage story in Jungle Action, covering issues fifteen through eighteen.

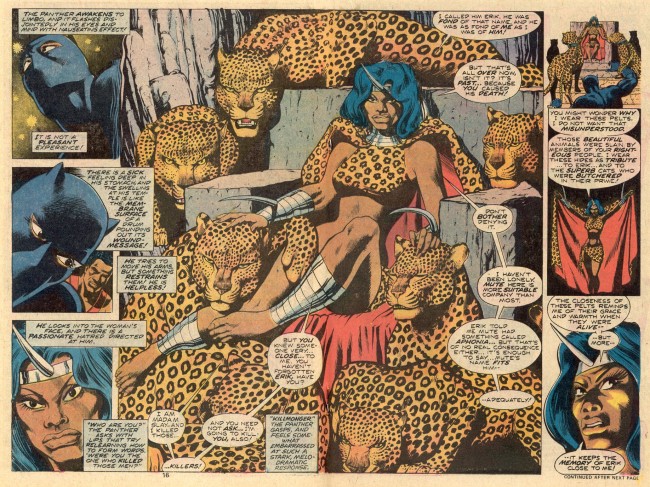

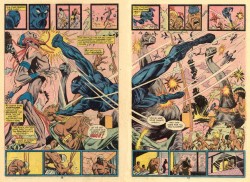

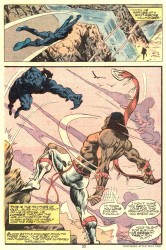

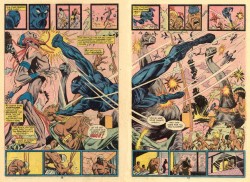

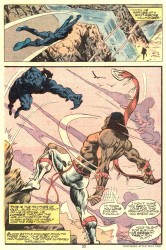

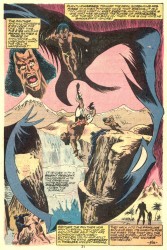

Here’s the end of the story: T’Challa makes his peace with his mistakes, in part by rejecting a certain portion of them, rediscovers his self-confidence, and goes after Erik Killmonger for his sins. They battle, and a rejuvenated T’Challa definitely holds his own… until Killmonger reasserts his dominance, explains that he was just playing with T’Challa, and easily lifts T’Challa’s body over his head and gets ready to snap his spine. That’s right: the hero makes his peace with his conflict, rediscovers himself, and does all the things that people are supposed to do before going off to fight the dragon, and he still loses. The battle isn’t even in question. Killmonger toys with him and then prepares to make a show of destroying him. No chance. There is no dignity, no honor in violence. Hey T’Challa, how’s failure taste?

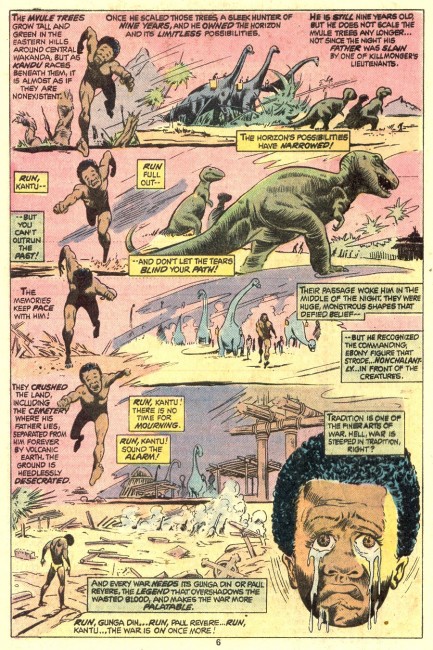

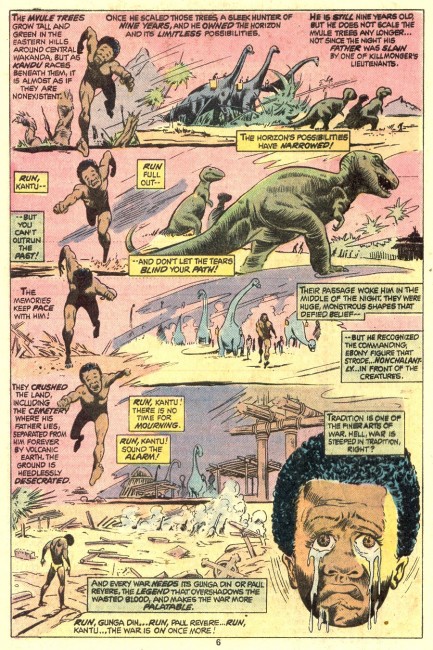

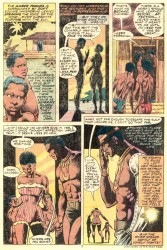

But there’s one thing that Killmonger, T’Challa, and the other larger than life characters in superhero comics forgot, and forget, about: the little guy. You know, the normal humans who provide so much flavor to superhero stories, and dead bodies when the need arises. In this case, Kantu, the son of the man who was killed by zombies, is the one that saves the day.

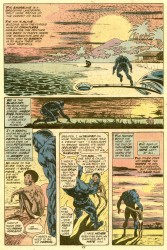

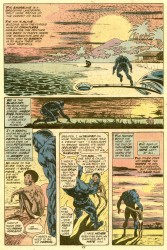

T’Challa had a brief meeting with Kantu on his way to battle Venomm for the last time. It’s brief and depressing, as Kantu is mourning his father’s death and T’Challa has no answers for him. McGregor’s typically florid prose has T’Challa asking “if there is any hope left at all.” Kantu, however, “does not know the words to ask such a question, but wonders the same thing.” After this meeting, T’Challa, like Spider-Man on a bad day, gives himself over to being the black cat, which “does not ask any questions. It needs very few answers or truths.” Violence is an escape.

Kantu is a casualty of T’Challa and Killmonger’s war. T’Challa gave birth to Killmonger’s rage. Killmonger’s rage resulted in the revenge scheme that killed Wakandans by the dozen, including Kantu’s father. Kantu is therefore, in the end, the ultimate representation of the effect of Killmonger and T’Challa’s conflict. The back and forth chess match, the tug of war of intellects between these two men are what formed all of the exciting scenes and drama. Kantu is a reminder that nothing happens in a vacuum. When a villain knocks down a building or idly kills a bystander, it counts. When a hero mows down dozens of bad guys with a machine gun and a one-liner, that is dozens of orphans being introduced into the world.

The idea of collateral damage being something that isn’t meaningless at all is an idea that Grant Morrison explored in The Invisibles in “Best Man Fall.” King Mob killed a nameless foot soldier early in the series. Issues later, Morrison dedicated an entire story to that nameless foot soldier, showing his life, his history, and the tragedy of his death.

We read stories and the only people that matter are the heroes and villains. Joker breaks out of jail, kills dozens, and then Batman pops him on the jaw and sends him back to jail. Six months later, it happens again. Stories that actually deal with the repercussions of that are rare compared to the ones that indulge in wholesale slaughter for the amusement of the audience.

Kantu, then, is what gets lost in the action. His father died something like eight issues ago, forever for a character created to die, and yet, here he is, taking center stage. Kantu demands attention, and when a young boy says, “I could kill him!” and speaks of hate, you should be paying attention, because something has gone horribly wrong.

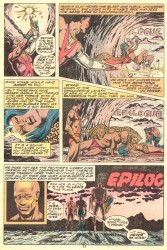

The real world, the place that hates you for existing and where people are cruel because that’s the only way to get results, came to Wakanda and took Kantu’s father away. When Kantu slams into Killmonger’s back, saving T’Challa’s life and knocking Killmonger to his death, that’s the end of his battered innocence.

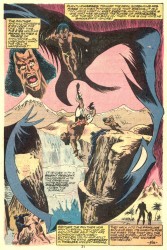

With two pages to go in the chapter, Kantu reappears and becomes the most important, and most tragic, figure in the book. T’Challa will go on with his superheroing, suffering larger than life wins and losses, but Kantu is normal. He doesn’t get to have the big wins that boost your confidence, the impossibly attractive temporary girlfriends, and the team of friends who smile and let you ride around in their jet. No, he’s just got his father’s remains, which T’Challa’s failure left out in the sun for two whole days, and his grief.

Now: Billy Graham.

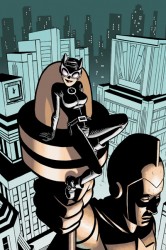

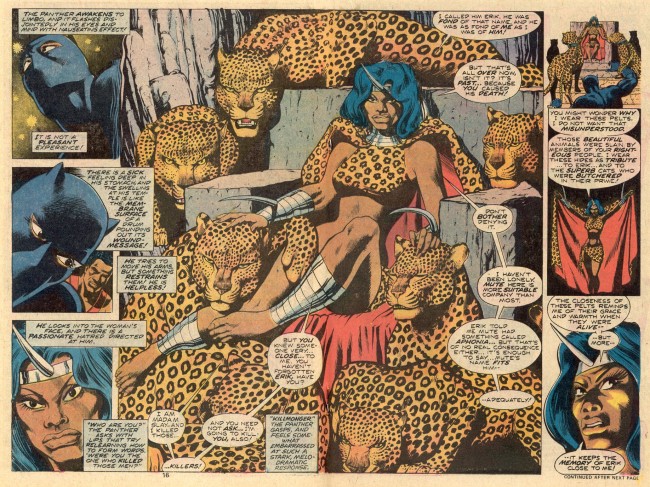

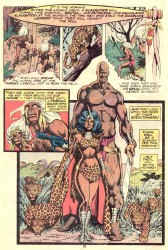

I like a lot of artists. Both Romitas, Jack Kirby, the entire Kubert family, Jim Lee, Chris Bachalo, Kevin Huizenga, Akira Toriyama, and dozens more. With his work in Panther’s Rage, Graham is solidified in my mind as one of the greats who has been sadly forgotten. He has inventive layouts that run counter to traditional comics thinking but are instantly understandable, grotesque and burly heroes, and a fantastic use of type.

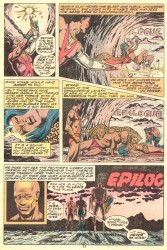

(The last true chapter of Panther’s Rage features the word “Epilogue” integrated into the sky on three pages. It doesn’t bring any new angles to text or push a certain theme. It’s just an artist who knows exactly what he’s doing flaunting his skill, and more power to him.)

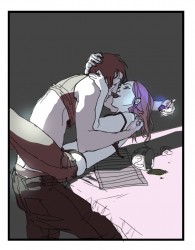

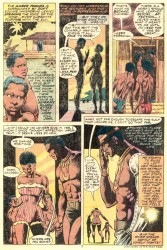

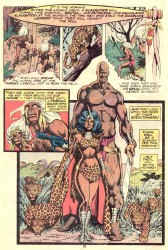

Graham can flipflop from Kirby sci-fi to hard realism between panels, and manages to make it all look cohesive. Embracing lovers, a broken marriage, a desperate run, and a little boy getting caught crying by the bank of a river all look exactly as they should.

He uses scale to great effect, he draws detailed backgrounds, his people look like actual people, his black people look like black people, and Kantu in particular is that kind of awkward and gangly mess of arms and legs that kids tend to be.

He drew the first seventeen issues of Luke Cage, Hero for Hire before moving onto Jungle Action. That’s the first issue of the first, or one of the first, ongoing comics starring a black American.

Billy Graham’s black, too. Comicbookdb suggests that he left comics after the ’80s. He died back in 1999. Check out his Wikipedia entry for more info.

Pay attention, because black history is everywhere.

Next: It’s not over.