Sons of DKR: Frank Miller x TCJ

April 6th, 2009 by david brothers | Tags: dark knight returns, dark knight strikes again, frank miller, interview, Sons of DKRThis is an interview in The Comics Journal Library: Frank Miller, a book I bought a few years back on a whim. It’s a fascinating read, both in terms of Frank Miller’s career and opinions and comics history since he got started. It’s currently out of print, I believe, but if you find a used copy somewhere, snap it up. I don’t know that I’ve ever read an entire issue of The Comics Journal, but there are some great interviews in this book.

I transcribed this interview on a lazy Sunday a few weeks back. It isn’t the full interview, but it is probably a little over half. I left out the bits that were not relevant to Batman: The Dark Knight Strikes Again, partly because they weren’t relevant and partly because I didn’t want to retype the entire interview.

This interview is a beast and a half. It’s almost 5000 words, but well worth reading. I do not have any commentary for it or pithy remarks. It can stand on its own. I’m posting it here because it deserves to be read, and because I’m going to be using it as reference and context for a couple of posts on Wednesday and Friday this week. I want to talk about a couple of books that owe a lot to Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, so maybe this will help me illustrate a few points.

I tried to go through and insert relevant links and images where needed, just to help with context and clarify a few points. Pardon the scan quality, as these aren’t my scans. Any errors are my own, though this should be pretty accurate.

DK2 As Satire

TCJ: Tell me a little about how you conceptualized the book. Did you see this as a satire?

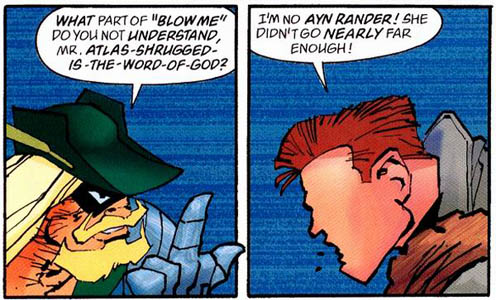

MILLER: Not exactly. No. The first thing I wanted to do was to try to take a new reader and make him feel the way I did when I was about 9. With the opening with the Atom and all of that. I tried to reinterpret each of these heroes by their powers. Most of my work now has been outside of superheroes, so if I want to get into intense melodrama, I’m probably going to do it in Sin City. The thing that makes these superheroes interesting is that they look really cool and they can do stuff. So what I was after, for the first third of it, was to reintroduce the idea of these powers being really cool. For instance, I don’t really give a damn about the Atom’s marriage. You know, that’s a stupid question. But it’s really cool to see somebody who can get really little. It was more a matter of saying, “How do I reintroduce this notion?” What I came across was that, to the reader’s eye, he doesn’t get little; everything else gets big. And all of a sudden, he becomes more interesting. Just like with the Flash. You never see him move. He’s already there. I thought that was a fresh take on these characters, to spruce them up. Like I said, I’m sick of hearing about their marriages.

TCJ: Did you go back and reread all of these characters, before you–

MILLER: I looked them over again. But it was mainly just… This stuff is on my hard-drive. I grew up on it.

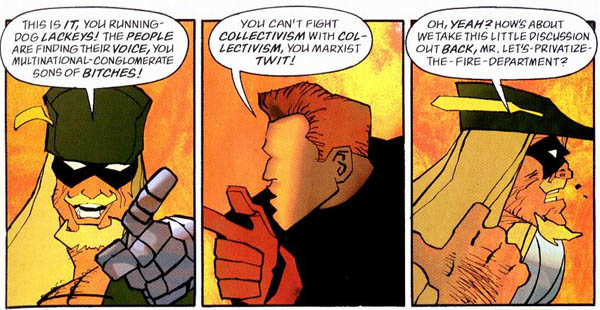

TCJ:Yeah, I enjoyed your little Randian screed.

MILLER: Oh, the Question? I was born to write that character.

TCJ: So there were satirical elements in it–

MILLER: Sure.

TCJ: –and I had a little trouble trying to get a fix as to what you were really doing. The story and the characters were slipping into, for me, parody as pop culture often does when it’s deconstructed enough. Was that one of your goals– to just keep deconstructing this to the point of parody or near parody?

MILLER: Near parody is fair, because I think that it kind of slides in and out of it. I just let that happen because that’s what felt right with the story. Because I felt that, every once in a while, you’ve got to take a deep breath and realize that you’re doing something intensely silly, and then go back to the operatic. For me, it’s the juggling of the two that creates a nice kind of tension. I think that perhaps what I was reacting to most was the over-reverential tone of so many modern comics.

One of the things I did was rewatch these old videotapes that I’ve got of the WWII Batman movie serials, this episodic, hilarious thing that they did– which was utterly racist, with those shifty Japs being the villains. None of which were played by Japanese, by the way, because they were all in camps, I guess. But there was something so idiotic and wonderful about it that I wanted to capture some of that. Also, I wanted to push things further, partly because I could.

TCJ: You said that you saw this as something you would have read when you were 9. Is that the age group you were aiming for? You have a certain degree of political satire in it.

MILLER: Well, who couldn’t now.

TCJ: And I couldn’t quite imagine a 9-year-old–

MILLER: No. I wasn’t writing it for 9-year-olds. I was writing to evoke the kinds of emotions that I had when I was nine, trying to get them out of people more like my age.

TCJ: Hmmmm, trying to get the emotions of a 9-year-old out of a middle-aged guy.

MILLER: Uh huh, the same way that Spielberg did with Raiders of the Lost Ark, for instance.

TCJ: On the other hand, there’s some really harsh political stuff in here, which–

MILLER: These are harsh, political times.

TCJ: A lot of this seems to be a reaction to the Bush administration.

MILLER: Yeah.

TCJ: IS that possible? When did you start this?

MILLER: No. When I started it, we didn’t have a president.

TCJ: OK. We were in that three-month period…

MILLER: I mean, we had a president, but we didn’t have a president-elect.

TCJ: And still don’t.

MILLER: [Laughter.] Oh, well, the case could be made. But it wasn’t until after I finished the first chapter that Bush was announced president.

TCJ: So that was very much on your mind as you were constructing this?

MILLER: Sure. Also, both candidates came across to me like computer-generated images. Their debates were the most bizarre I’ve ever witnessed. And I remember watching one of them thinking that I was expecting one of them to digitize, to pixilate in front of me. That’s where that gag came from. So I came up with a generic president who was named after the president in a truly horrific old DC comic called Prez.

TCJ: Oh yeah, Joe Simon‘s comic.

MILLER: It’s up there with Brother Power, The Geek. I used that as a cipher.

![]() TCJ: To what extent is the satire in the book based on what you believe is actually happening in the country? One of the diatribes you put in Batman’s mouth is “We blew it, Barry. We spent our whole careers looking in the wrong direction. I handed down muggers and burglars when the real monsters took power unopposed.” Is that what you think is happening? On a lesser, more subtle scale?

TCJ: To what extent is the satire in the book based on what you believe is actually happening in the country? One of the diatribes you put in Batman’s mouth is “We blew it, Barry. We spent our whole careers looking in the wrong direction. I handed down muggers and burglars when the real monsters took power unopposed.” Is that what you think is happening? On a lesser, more subtle scale?

MILLER: Well, it would be more subtle. This is where you and I tend to disagree. I don’t think this stuff happens in a Mylar-snug vacuum. I think that it’s when this kind of material works, it’s drawn from the sources around you but it’s turned into metaphor. I ‘m waiting for the pop-cultural metaphor for 9/11. I haven’t seen a sign of it yet. But just like Invasion of the Body Snatchers was a response to Communism, and film noir itself was a response, essentially, to Pearl Harbor and the Second World War, there will be something that surfaces. It might be a Western. It won’t, superficially, resemble what happened. But I feel that you have to process all of this stuff through pop culture or else pop culture is the meaningless cotton candy that you often say it is. My feeling is that superheroes should be all over politics, sex, you name it. And it’s only a kind of dumb history of self-censorship that has kept it from being so.

TCJ: In that case, aren’t you saying that superheroes should be read, not so much by kids as by adolescents and adults?

MILLER: Well, they already are.

TCJ: Well, they are almost exclusively now, yeah.

MILLER: We may have different ideas about what kids can read. You’ve got one. I don’t. But I was reading Mickey Spillane when I was 13, and that was some pretty racy stuff. To me, it’s really up to parents and kids to figure out what they want to read at what age.

TCJ: Right, right. But you are saying that superheroes have really moved to be an adult…

MILLER: Well, but there’s revenge and all kinds of stuff in Astro Boy. Why do we say that we have to wait until people are 18 for them to be engaged in these kinds of issues? Sexual awakening is in the single digits, so do we just drop them into it? I don’t know. It’s a whole other debate.

TCJ: But it seems to me that satire has to be simplified for kids. Spillane, for example, isn’t sophisticated in literary or political terms, so if you’re aiming at a 13-year-old audience as your youngest…

MILLER: Also, I think if you showed a 7-year-old that Superman and Wonder Woman tryst, he’d think they just went for a flight.

TCJ: I should have tested that thesis out at home. I think that’s quite possible. But that’s perhaps likely because you were coy enough to have it both ways.

MILLER: Well, and again using metaphor.

TCJ: I noticed the NudeTV was never entirely nude.

MILLER: Well, I placed the lens carefully.

TCJ: Right. Why is that? If it’s just going to be read by adults, why bother?

MILLER: Well, I don’t know. It felt right. This wasn’t Sin City. And I was already doing my best to offend everybody every other which way.

QUOTING FRANK

TCJ: We’ve already come to the point where I’m quoting you. I should preface this by saying that I read Dark Knight II and I was… I was unresolved as to what to make of it.

MILLER: OK.

TCJ: Anyway, one of things you said in the last interview that we did was, “It’s a sad, sad thing to say and I hate to say it, but the lack of ambition, creative ambition, I mean, shown by mainstream artists, has been disheartening. Even bizarre, in the case of those of us, the lucky few, who have been told by publishers that they’ll bankroll whatever we want to do. Get an offer like that, and run off to do some dead old character and embrace the role of employee all over again.” [Miller laughs heartily.] “Go back to answering all of those squads of editors. Yeah, that drives me nuts, when I think about the talent that has been wasted. Great opportunities are being wasted. We’ve come so far, but we don’t seem to be doing all that much with it.

MILLER: Right.

TCJ: Obviously, you can argue that you did try to do more with it. But there does seem to be a recurring habit among people who started off in mainstream comics that they keep coming back to it and doing these dead old characters.

MILLER: Yes, I know. I think that we have, sometimes, different reasons. In the case of this stuff, I had a couple of particular reasons. One was that I just really felt like doing it, and I didn’t want to go off and create Ratman and pretend that I wasn’t doing Batman. I felt like doing this comic. The other thing is that, every once and a while, you want a big bullhorn. Because pop culture, and I keep referring to it that way, really is what I regard my work as. Pop culture is not something that wants to be off to the side. So to come back and do this sort of thing for a while is a lot of fun and gets a lot of attention, and I get to play with some icons and it doesn’t stop me from doing what I want to do next.

That was a good quote. It was really embarrassing when you read it to me.

TCJ: Well, it jumped out of that interview, I must say.

MILLER: I’ll bet it did.

TCJ: So, if you could sum it up for me, what was the thesis of the book? What were you trying to put across? I couldn’t quite resolve for myself what you were doing, because there seemed to be contradictory–

MILLER: Well, for one thing it was a book that was violently disrupted smack dab in the middle of it.

TCJ: By the September 11 attacks?

MILLER: Yeah, because it was a romp. It was, “Let’s play with this stuff and let’s have some really fun parody.” And then 9/11 happened, and I had just run a flying Batmobile into a skyscraper and blown up downtown Metropolis. I hit the bricks.

TCJ: It didn’t seem appropriate to do it any more?

MILLER: Well, I couldn’t keep going without addressing it. So I had to stop the story and make it take a darker tone. Somehow, I found that in a certain way, dramatically, the darker you get, the funnier you get, because after a while you have to laugh. The visual ideas pop out, like the idea of a Batman with three teeth. I couldn’t resist doing that. Also, all of the stuff that’s implicit in superheroes, the idea of there being these mightier creatures around. Obviously, this is stuff that Alan [Moore] and I played with in the old days, and that people have been playing with for a long time–but there is a certain fun to that, but it’s kind of scary. It’s kind of Teutonic, which is funny since the superhero is a supremely Jewish creation.

TCJ: This book took two years of your life, right?

MILLER: Yes.

TCJ: And that was nothing but working on Dark Knight?

MILLER: Yup. It would have been less, but for the interruptions of the move to New York and 9/11. It was just the way life went.

TCJ: To what extent did 9/11 affect you personally or creatively?

MILLER: Seriously, for at least the foreseeable future, it’s the whole point of my work. I’m going to play around with doing some propagandizing.

TCJ: I was struck by how closely one of Batman’s speeches actually sounded like a terrorist manifesto.

MILLER: I know. That was early on.

TCJ: Was that deliberate?

MILLER: When he said, “Striking terror. Best part of the job,” that was before the attacks. Then I was stuck with it. Because DC left it up to me whether the book would be changed, because the parallels are just creepy. I decided to write my way out of it. That whole period of time in this city… it was the flock of war. There were fighter planes flying over my home. Of course, every time I heard a plane, you know what I thought. So it was a very tough time to make those kinds of decisions.

It’s weird, Gary, because almost anybody with my job will tell you that when we’re asked to sign a book or something, we’ll remember what we were going through when we did it. But this time, it happened in the book. So this series in particular is one where it’s painfully vivid.

TCJ: Of course, on page 183– which must have been done after 9/11– you have this speech by Batman: “This is only the beginning. Tyrants, your days are numbered. You can’t fight us and you can’t find us. We strike like lightening and we melt into the night like ghosts.” If you look at it form the point of view of radical Islamists, of course we are tyrannical and that is their credo.

TCJ: Of course, on page 183– which must have been done after 9/11– you have this speech by Batman: “This is only the beginning. Tyrants, your days are numbered. You can’t fight us and you can’t find us. We strike like lightening and we melt into the night like ghosts.” If you look at it form the point of view of radical Islamists, of course we are tyrannical and that is their credo.

MILLER: Oh, that was deliberate. Yeah. Because I long ago determined that a character like Batman can only be defined as a terrorist if his motto is striking terror. I didn’t want to dodge it and also, I wanted Batman to creep you out. That I wanted from the start. I don’t want you to like this guy.

TCJ: He’s also the hero. How do you reconcile those two– the terrorist being the hero? He’s trying to save the country from a totalitarian government.

MILLER: He is a hero, but heroes don’t have to be likable. I mean, if you really look at Sean Connery’s James Bond, he’s charming, he’s brilliant, but he’s really a dick.

TCJ: Yeah. You wouldn’t like him if you met him.

MILLER: Yeah. My feeling about Batman is that he’s similar in that you’d want him to be there when you’re being mugged, but you wouldn’t want to have dinner with him. The way he cheers Hawkman on as he crushes Luthor’s skull… for me, it was really the idea coming into its own without the bullshit on top of it being a socially acceptable role model and all of that.

TCJ: But in James Bond, these contradictions don’t have to be resolved because they’re not positing serious ideas whereas you are, aren’t you?

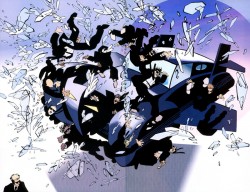

MILLER: So was Kubrick in Dr. Strangelove. Comedy can be political or not. And from the masterpiece Goldfinger on, the Bond movies were comedies. Comedies can be damn scary; Herblock’s best Washington Post cartoons in the Nixon era were brutal jokes. Much as I love the wild adventure of superheroes, they have a comedic aspect. They’re over the top. Even silly. Using them to jump all over the current political situation is irresistible. Look, we’ve got John Ashcroft as attorney general. You can’t make this shit up.

TCJ: Now it seems like you take a certain pleasure in beating up Superman.

MILLER: I know. Why is that? I must have issues. I don’t know. There’s always been something about Superman that says, “I can fly and you can’t.”

TCJ: You want to give him his comeuppance?

MILLER: Yeah.

TCJ: I must say, and this is sort of a minor point, all things considered, but the sex scene between him and Wonder Woman struck me as down-right bizarre where he just has the living shit kicked out of him and he looks like hell, he’s all beat up, and her first response is to punch him again and then to fuck him, I guess. And then right after that, he’s great. How did that work?

MILLER: That’s just him.

TCJ: What we call artistic license?

MILLER: Yeah. That’s mythic thinking. The rejuvenating effect of sex.

TCJ: Huh.

MILLER: That she’s a life giver. That women are nurturers and life givers and that, by their joining, he is renewed and he’s actually younger for the rest of the book, too. That woman must have some powerful mojo. Also, she slugged him because she’s a damn Amazon, and it sets up the fact that their daughter is a bitch.

MILLER: That she’s a life giver. That women are nurturers and life givers and that, by their joining, he is renewed and he’s actually younger for the rest of the book, too. That woman must have some powerful mojo. Also, she slugged him because she’s a damn Amazon, and it sets up the fact that their daughter is a bitch.

TCJ: OK. I’ll buy that.

MILLER: Would you expect Amazons to be nice?

TCJ: I’m not sure. I haven’t thought through the Amazonian question.

There’s a spontaneous look to the work in Dark Knight II, but obviously that doesn’t necessarily mean it was spontaneously composed. How much preparatory work do you do?

MILLER: I did a hell of a lot of preparatory drawings— dozens of them. I did various versions. I must have done at least six versions of Wonder Woman, and these were fully inked drawings. [one, two, three, four, five, six, seven] It just turned into this heap of drawings as I tried to find my way to it. I like to prepare forever and then execute like lightning. That’s just the way I like to work in general. For instance, if I’m writing a story, it takes me much longer to plot it than to script it.

TCJ: I see. You like to maintain spontaneity in execution?

MILLER: Yeah. Absolutely. William Goldman once wrote that it’s best to write fast. I believe that, but I also think it’s best to plot slowly.

TCJ: So that you can write fast?

MILLER: I can script fast, yeah. I tend to break everything down into little post-it notes that I put on my wall. And I put it together structurally. It’s the part of the job that I hate.

TCJ: You must have had a big wall.

MILLER: Yeah, I’ve got some big walls. I don’t have any pictures on my walls except for newspaper photos that I stick up there. I use all of my walls as an extended drawing board.

TCJ: Did you plot out all three chapters in advance?

MILLER: Yeah. Not in total detail, but I had everything– including the ending– planned before I did page one.

TCJ: How precisely is it broken down? Is it broken down by page or just roughly by chapter?

MILLER: No. For each chapter, I gave DC a scenario that was probably about 25-26 pages long, typed. It gave no indication of what happened on which page. I always find with these things that it’s good to play everything, but when it’s actually on the drawing board, a lot of ideas completely falter. You realize that something you thought was this brilliant subplot is a one-panel gag or it’s nothing. So there’s a lot of room for changes.

TCJ: And I assume that new ideas come up as you go through it?

MILLER: Oh yeah. The whole middle of the story tends to change shape on me.

TCJ: Tell me a little about the editorial process. When you submit this prose…

MILLER: Scenario.

TCJ: Is that basically rubber-stamped and then you proceed? Or do they discuss this with you at some length?

MILLER: That’s where, in this case, it’s in Schreck’s hands. He reads it over and he’ll call me back. He had very few suggestions along the way. Mainly, he was looking out for their interests, to make sure I don’t go too maverick on them. On the other hand, the project had such momentum and he’s a fairly progressive guy that there wasn’t much pressure that way. He would just say that something was a little confusing.

TCJ: So someone above him had to have read this as well.

MILLER: Yeah, I’m sure.

TCJ: And then he talks to them and gets back to you and serves as an intermediary?

MILLER: I imagine. The great thing he keeps me from that most of the time.

TCJ: Do you find this kind of editorial process valuable in any way, or is it just something you tolerate because it’s there?

MILLER: [Amused.] When I’m dealing with a company like DC, I mostly think that they basically want to make sure that I don’t mess up their trademark. There will be moments where they’ll say, “I don’t think this is clear” or “You have to cover this,” and there will be story comments. But on this project, at the level of the synopses themselves, there wasn’t much trouble.

TCJ: Was there any trouble when you actually executed it?

MILLER: Yeah.

TCJ: At what stage? Do you send them pencils?

MILLER: Yeah, because I didn’t letter it. I’d bring in the pencils and they’d be lettered and so on. But there was some arm wrestling. This was after things were inked. It does happen. I’m not going to get more specific.

TCJ: Were they minor?

MILLER: No. But we worked them out.

TCJ: And you were satisfied with the way you worked them out?

MILLER: Yeah.

TCJ: Well, you have to wonder exactly what they would object to.

MILLER: Or what they wouldn’t.

TCJ: Right. I assume that they probably would have objected to what you did if someone else had done it.

MILLER: Oh yeah. Oh yeah.

TCJ: It’s this whole political–

MILLER: No, it’s not just political. I’ve got a track record. They’re taking less of a chance.

TCJ: Well, when I say it’s political I meant it comes down to pragmatism, in the sense that they know that they’re going to get a return and that they therefore allow you more latitude than they’d allow some Joe Blow who is not going to do as well from a commercial standpoint. They’re trading potential difficulties with their trademarks for the cash that’s going to accrue and that’s factored into it.

How did you come up with the visual stylization? It’s somewhere between Big Foot and your Sin City style, but it’s–

MILLER: By the way of Alley Oop. Again, I was trying to make the stuff less formal. I wanted the superheroes to build up the parts of them that I thought would make them look the most heroic. In the case of Batman, I didn’t want barrel-chested. I went big shouldered and big formed and obviously gigantic hands and feet. It was a variation on what I do, for instance, with the women in Sin City, where they break down to a few curves to evoke. It was an attempt at something, because I thought everything had gotten too damn realistic. I like to enjoy what comic books can do that film can’t. There seems to be a bit of a hang-up now for people to make their fantasies real. I’d rather be doing Calvin & Hobbes than Rex Morgan.

TCJ: It’s interesting that you should say that, because I thought that there were some parallels between this and The Matrix.

MILLER: Really?

TCJ: In the sense that there is a totalitarian society that a handful of people are fighting against in an action context.

MILLER: Yeah. Well, I think we’re going to be seeing a lot of that these days.

TCJ: Because?

MILLER: Right in the middle of this book, John Ashcroft shows up. Excuse me. This guy’s the attorney general? I mean, he’s straight from central casting.

TCJ: As is Condoleezza Rice.

MILLER: She’s amazing.

TCJ: A ruthless femme fatale if ever there was one.

MILLER: Kind of our Lady Blackhawk.

TCJ: Speaking of the parallels that you want to draw between this and what you see around you, how do you envision, in Dark Knight II, it coming to this state of affairs? Do you see it essentially coming as it did in the real world, which is that democracy has simply been slowly eroded?

MILLER: Well, you’ve got a population that doesn’t care about it and a bunch of people who don’t want it, and they’ve got a lot of money. Somewhere during the whole election fiasco, people were calling it a coup. All I could think was, “No. It’s a hostile takeover.” So as much as a bromide as it is, there had to be a corporate villain here, so that the president really was just a puppet. Come on– they’ve got Lex Luthor, why not?

TCJ: It seemed like the parallels were pretty dead-on.

MILLER: Thanks. This stuff’s too easy, though. I try to top it, but…

TCJ: Well, that’s the other problem. In a way, it does seem too easy. The parodies of the media, for example. There is, of course, nude TV news.

MILLER: I didn’t know that when I did that. I don’t watch enough TV.

TCJ: Unfortunately, I haven’t seen it myself, but I know it’s out there. It has been around for a few years, I guess.

MILLER: Yeah. I missed that.

TCJ: I assume it will only be a few years more before it’s on the networks. Although, God knows, we don’t want to see Dan Rather in the nude.

MILLER: No thanks. Or Chris Matthews.

Absolutely fascinating and awesome. Thanks for posting it (and more importantly: thanks for transcribing it, that must have been hellish).

I only read The Dark Knights Strikes Again late last year. I had held off getting it for so long because… well, I guess I was kinda afraid that it would be as bad as people generally say it is. I am glad to say that I absolutely loved it. I would even go so far as to posit that DKSA is the kind of thing comics should attempt to be like more often. It’s clever, funny, inventive, multilayered, ambitious, and, most importantly, it actually has something to say.

In fact, I believe that it’s one of the best comics published in this decade (and perhaps in any decade), and I hope that history will render a fairer and more positive judgement than contemporary readers have.

Thanks for posting this. DKSA was not what I expected it to be when I read it years ago, and while it’s far from my favorite book, I respect Miller for what he was trying to do with it.

I really enjoy DKSA for what it is. My big problem isn’t the ridiculousness of the writing, which I enjoy in an off-the-wall-bugshit kind of way, but the artwork, ehich, especially in the last chapter, looks horrendous

The stuff about making the powers of the Atom and the Flash cool again — essentially by depicting them the opposite of the way they’d always been done before — is exactly on target. But he lost me again with “…a truly horrific old DC comic called Prez.” Prez was a) awesome and b) smarter and far less nutty than Miller’s own treatment of politics.

Yeah, I’ve always loved this interview. No question Miller is a one of a kind guy. Never really liked his art too much. I’m really looking forward to what else is coming down the pipe this week.

[…] the record, any images or text is from DKSA or the Miller x TCJ interview I transcribed the other […]