Black History Month 2011: Billy Graham

February 4th, 2011 Posted by david brothers

Billy Graham

Selected Works: Essential Luke Cage/Power Man Vol. 1, Marvel Masterworks: Black Panther

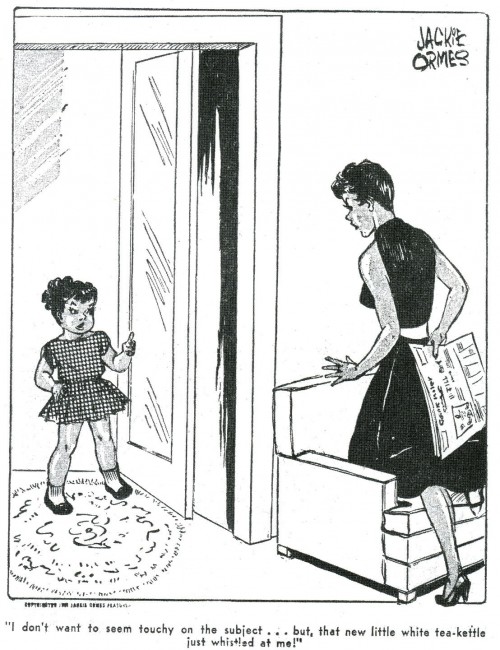

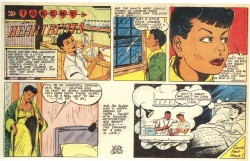

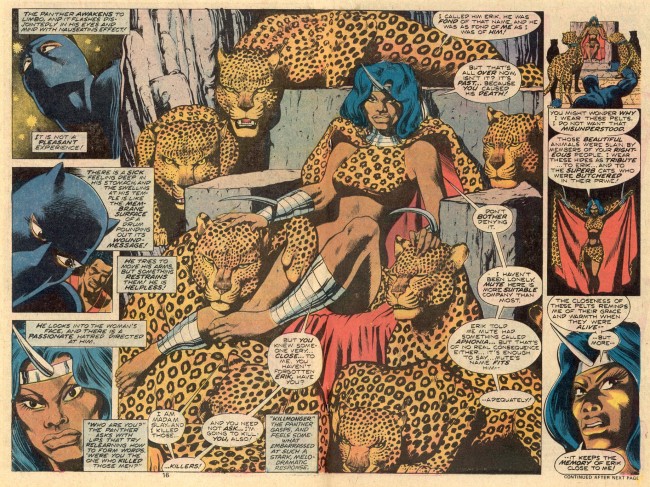

Billy Graham is an art monster. He helped define Luke Cage for the first sixteen issues of Hero for Hire and he worked on what is still the best Black Panther story of all time: Don McGregor’s Panther’s Rage. Prior to that, he worked at Warren and banged out some perfectly solid horror comics work.

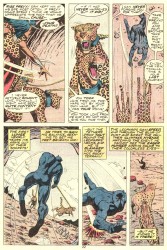

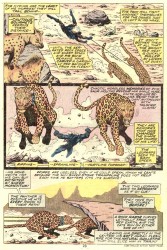

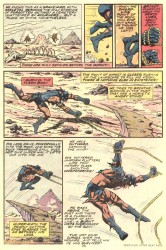

This guy draws great comics, with a Gene Colan’s figurework meets Jack Kirby’s explosive action sort of thing going on. He has these wonderfully proportioned and fairly realistic figures doing insane Kirby judo throws and flips. Characters have genuine facial expressions, often exaggerated for effect but still reasonable, and idealized bodies. Graham can even draw people of different races without descending into caricature, a gift that some modern artists can’t even match.

More than that, though, is that Graham’s art is raw. There’s this looseness or roughness that make his pages really interesting. They aren’t unfinished or lacking in detail, but the detail they do have is rendered in a way I don’t see too often. His work is chunky and scratchy, and I always feel like if you could wipe away the color, you’d see pencils that were worthy of being shot straight from the board.

Graham’s Kirby-influenced realism was vital for both Cage and Panther at the time, I’d say. The two books depicted a Marvel universe that varied from being even more street level than Amazing Spider-Man to being about half as cosmic as Fantastic Four. Graham’s art split the difference. Cage and Panther were both grounded, but not so grounded that they couldn’t expand into more comic book-y situations. If you look at something like Daredevil, which has been banging the Early ’80s Frank Miller Drum for entirely too long now, you see a series that has been defined and limited to one style. Graham was just street level and cosmic enough to make everything work.