Nobody in comics draws quite like Chris Bachalo.

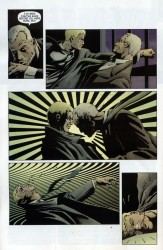

I’ve seen people complain that his work is too confusing, hard to follow, or too jumbled. There may be a point there, but not one that I ever really agreed with. Bachalo’s art is dense. He draws in a way that fills panels with details. He doesn’t do the Bryan Hitch thing, where every jet has several realistic parts. He’s not Moebius or Katsuhiro Otomo, so he’s not throwing in every detail there is to throw in. No, Bachalo has more in common with Geof Darrow than any of those guys.

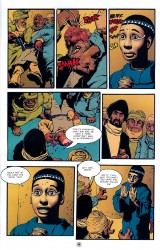

Darrow and Bachalo have a style that can be described as “obsessive.” In Shaolin Cowboy, Darrow drew every rock and lizard and butt crack he could get away with. His figures look like real people, but as you look at his work, you see more extraneous information than you would with the average comics artist. There are too many details, too many little touches, for them to be realistic.

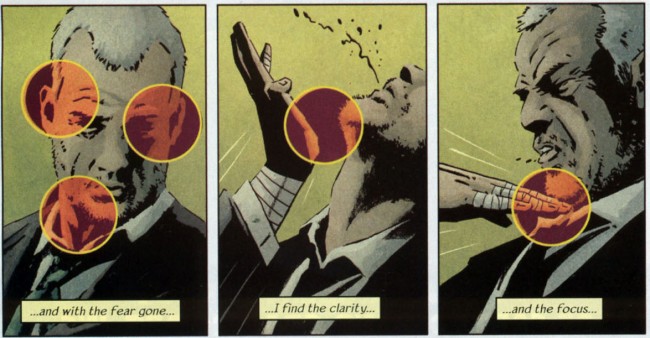

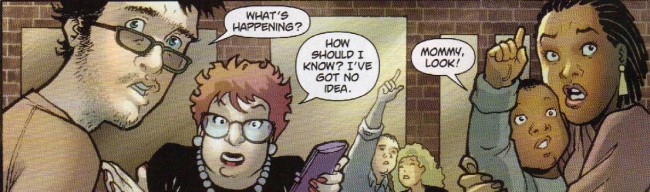

Bachalo’s work is similar, though for different reasons. Bachalo doesn’t even try to replicate reality in his work. He’s more concerned with replicating the experience of life, rather than the appearance. In essence, where Hitch or Otomo try to make their drawings as close to real life as possible, Bachalo wants to replicate the feel of real life via caricature. Bachalo’s approach is fascinating, and makes for exciting, and beautiful, comics. The closest person to his drawing style in American comics is Humberto Ramos, but that is more due to the fact that they have complementary styles, rather than styles that resemble each other (i.e., Alan Davis & Bryan Hitch).

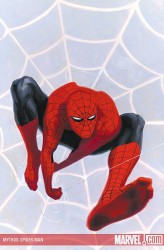

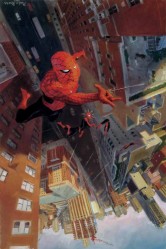

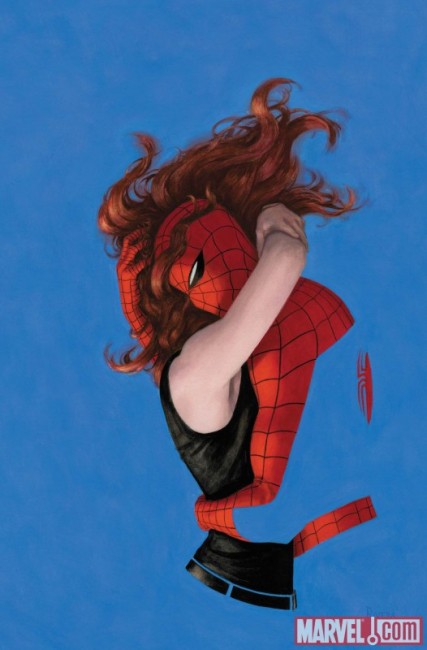

Bachalo draws these smooth, Play-Doh-type people. They have smooth skin, prominent noses, gelled-up hair, and wide mouths. Bachalo doesn’t go in for the muscles-upon-muscles style of superheroic art. Instead, he shows how powerful someone is by simply drawing them bigger and broader than everyone else. His Spider-Man is tiny and fairly muscleless, but he’s also lithe and practically a contortionist.

One of my favorite visual gags that Bachalo has drawn came early in Amazing Spider-Man: Brand New Day . J Jonah Jameson, after suffering a heart attack, is in the hospital, crankier than ever before and ready to go. He sneaks outside into the snow, barely making any headway against the wind. Panel five has the money shot–James with his leg thrown out far, bound and determined to take another step while a nurse drags him back inside.

. J Jonah Jameson, after suffering a heart attack, is in the hospital, crankier than ever before and ready to go. He sneaks outside into the snow, barely making any headway against the wind. Panel five has the money shot–James with his leg thrown out far, bound and determined to take another step while a nurse drags him back inside.

That one panel is a perfect look at how Chris Bachalo uses caricature to create believable body language. It’s not realistic by any means. The snow is a big ball of blurred white, Jameson’s gown is just a little wrinkly, and his neck is way too long. This is practically a Three Stooges or Buster Keaton shot in comic book form. Jameson’s exaggerated motion, along with his stick-thin legs, enormous chin, and long neck, all work in concert here to tell you everything you need to know, clear as day.

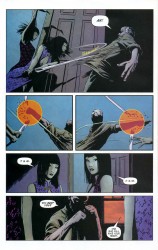

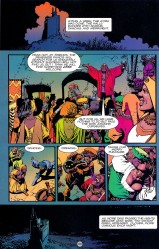

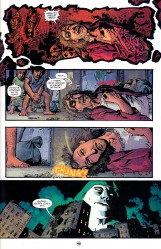

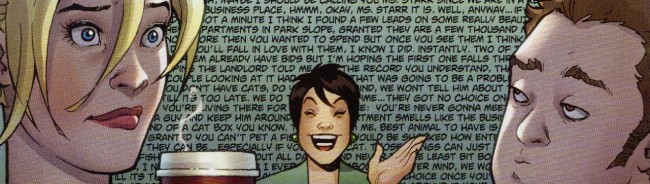

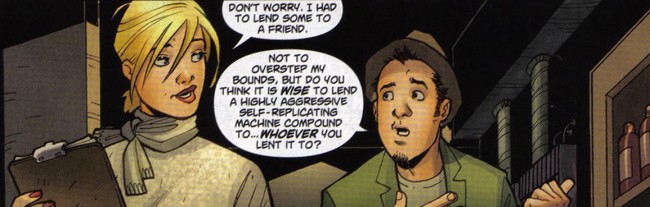

Bachalo is a master of acting. In this page from Amazing Spider-Man: Shed, Carlie and Peter are having an impromptu lunch. Bachalo uses close-ups to frame the page and three wide panels to show the actual action. Peter has a Ralph Dibny nose when he goes “Cheers” with his cup, Carlie’s carefully dabbing at her mouth after a messy bite, and her relaxed lean in panel four is killer. The quiet laugh in panel five is pretty great, too. Peter and Carlie come across as comfortable and friendly, and you don’t need dialogue to figure that out. It’s a little goofy, a little funny, but it’s great work.

What’s interesting about this page is the way that both people are drawn. Peter and Carlie both have Ralph Dibny or Mr. Magoo noses, strangely round jaws, and there’s a bit of Colin Mochrie in Peter’s face. Carlie’s mouth is unnaturally huge in panels five and six, especially in six. It’s kind of weird that she’s clearly taking little bitty baby bites out of that sandwich with her big ol’ mouth, but that doesn’t matter any more than the big noses and Peter’s weird hair does. Bachalo warped them in tiny ways, but uses that to his advantage.

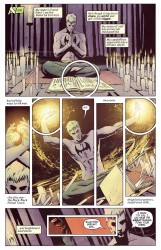

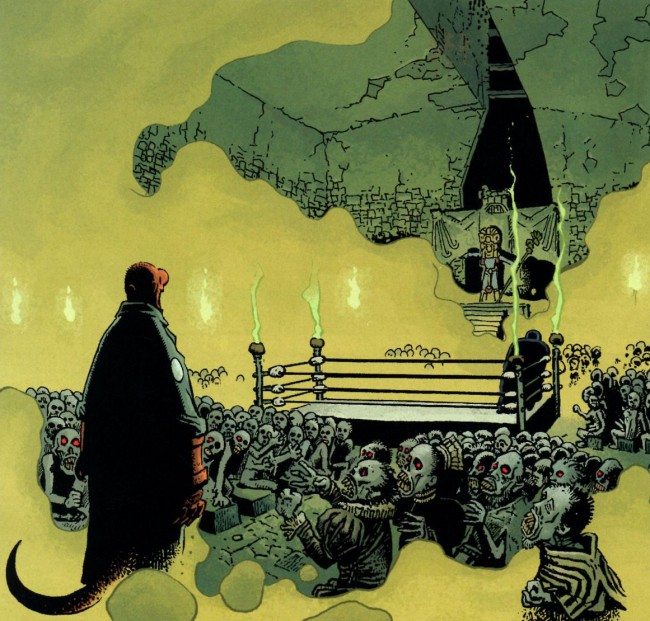

Bachalo uses unrealistic proportions well, but what he’s best at is playing with space. His mostly-white two-page spread from X-Men: Supernovas is beautiful, with the left-hand side being stacked with the aftermath of an attack, including some adorable flopping fish, while the right side is left largely empty. The composition is impeccable, perfectly displaying the chaos of half a second previous and the quiet moment just after.

is beautiful, with the left-hand side being stacked with the aftermath of an attack, including some adorable flopping fish, while the right side is left largely empty. The composition is impeccable, perfectly displaying the chaos of half a second previous and the quiet moment just after.

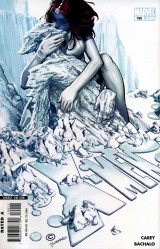

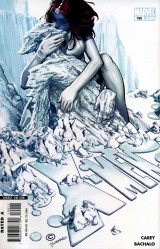

I’m really fond of the cover to X-Men 190, too. Again, it’s very busy, overflowing with information in the form of clumps of ice, puddles of water, and the mountains in the background. The best part of the cover is the embrace between Mystique and Iceman. She has long arms and fairly thin shins, but she’s all round angles and smooth. Iceman is the opposite, with hard-edged ice, broken limbs, and a pointy face. I can’t quite put my finger on it, but something about this cover stuck with me. Maybe it’s the way the blue and greys blend together (which I think is due to Antonio Fabela, Bachalo’s usual colorist) or the splash of color that is Mystique’s hair. It’s a striking image, and positively claustrophobic.

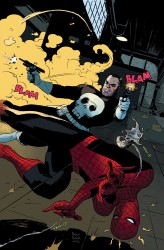

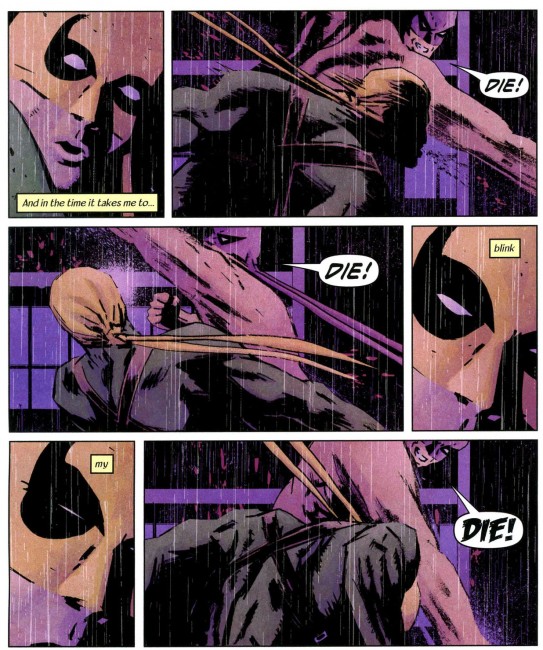

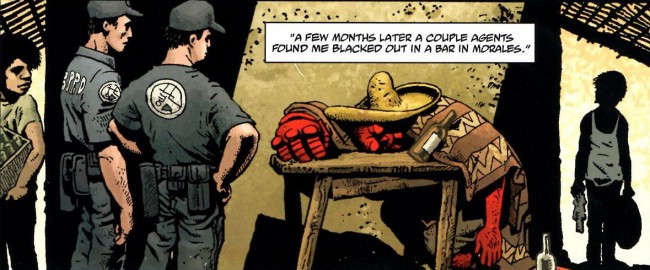

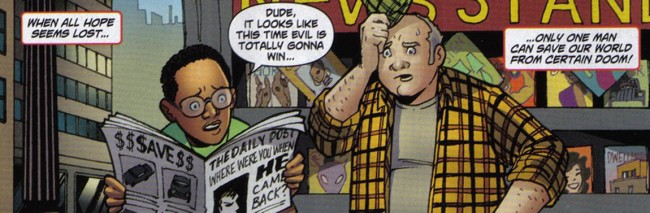

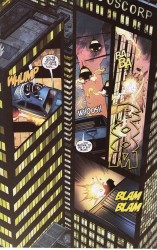

In this page, where Spider-Man has a guy strung up and is trying to scare him straight, the panel is tilted to the left and comparatively filled with information. The chimney stacks, water towers, and brickwork all work to show you exactly where this is taking place, but the real meat and potatoes are Spider-Man and his webs. Bachalo draws the best webs since Todd McFarlane left the Spider-books, and he’s just showing off here. Bachalo’s Spider-Man is crunched down into a tiny ball, ready to spring, and has huge and expressive eyes. There’s a lot to look at here.

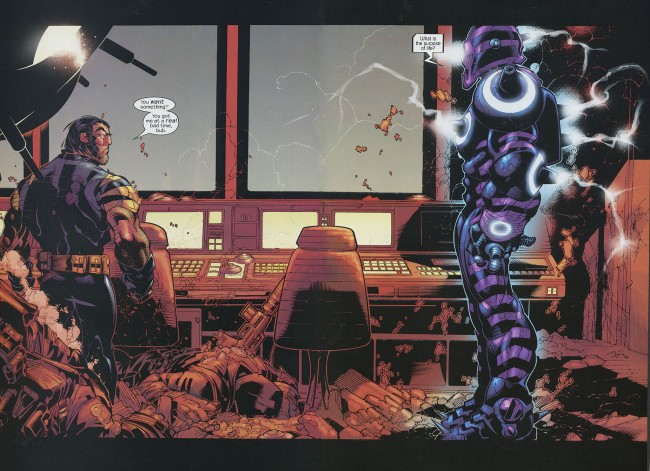

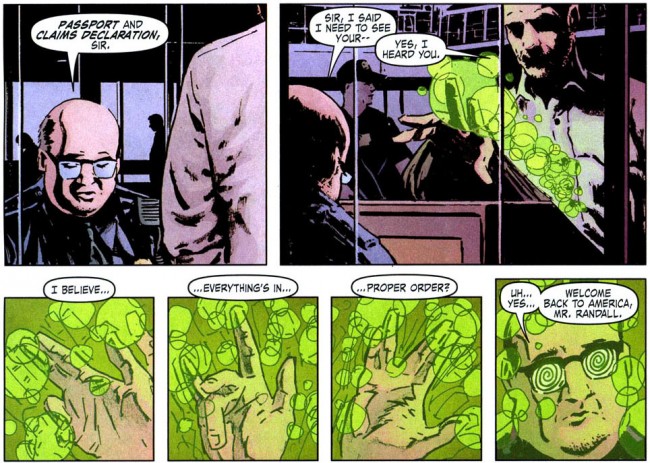

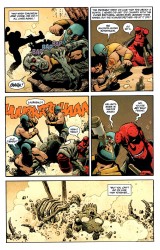

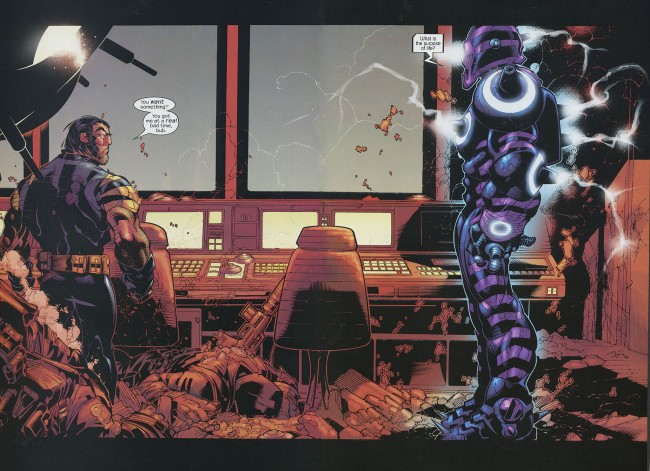

Look at the image of Hammerhead, from Amazing Spider-Man: Crime and Punisher . This is how Bachalo shows power. Hammerhead is huge. Hulk huge. The scale would have you think that the kid in the foreground is barely a toddler, but no. He’s in his pre-teens. Hammerhead is just that big, and he’s half-crouched. One of his fists is as big as the kid’s head. The page is weighted toward the background, making the kid look even smaller. This is an effective choice, in part because it instantly gets across how dangerous Hammerhead is, even without the piles of beaten and brutalized bodies behind him.

. This is how Bachalo shows power. Hammerhead is huge. Hulk huge. The scale would have you think that the kid in the foreground is barely a toddler, but no. He’s in his pre-teens. Hammerhead is just that big, and he’s half-crouched. One of his fists is as big as the kid’s head. The page is weighted toward the background, making the kid look even smaller. This is an effective choice, in part because it instantly gets across how dangerous Hammerhead is, even without the piles of beaten and brutalized bodies behind him.

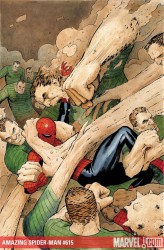

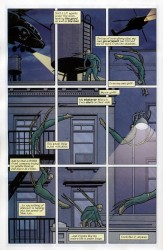

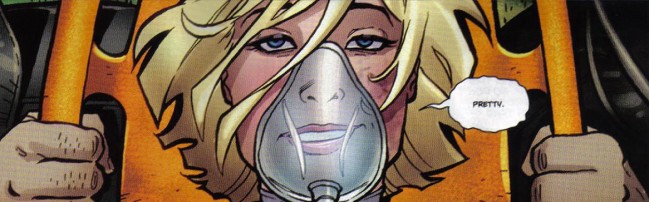

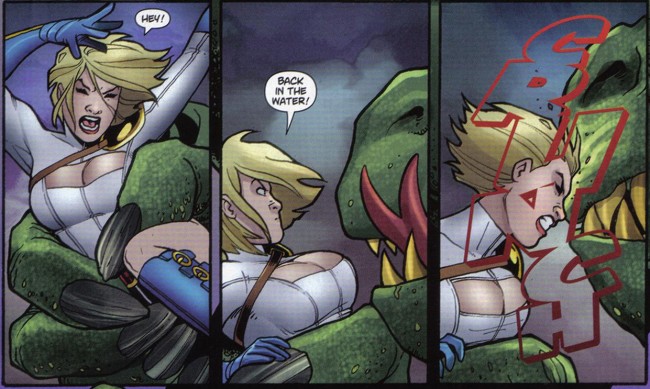

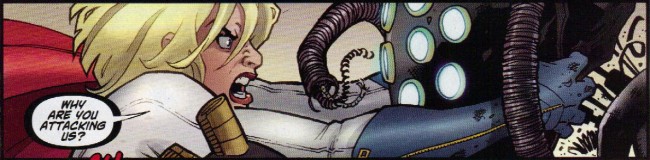

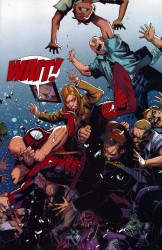

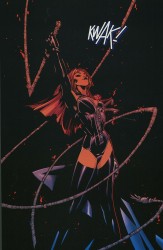

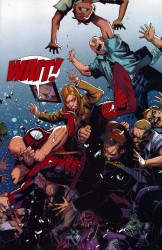

Space and scale again. The Lizard dominates this page from Shed. He’s enormous and right in Spider-Man’s face. All of the details on the page go to the Lizard, leaving Spider-Man featureless, save for his wide eyes. A later page features Spider-Man swarmed with civilians, buried under a mass of them and drowning in the chaos.

Bachalo alternates between flooding a page with information and leaving them wide open. This is the way storytelling in comics should work. Every element of his work is done in service of the story, whether the characters are warped and compressed under the pressure of all the debris on the page or given room to breathe. He’s killer, and extraordinarily suitable to drawing Spider-Man comics. His take on the character gives you a short, fairly skinny version of Spidey, a take that works really well and makes everything a little more interesting.