Jormungand 3: “To promote world peace.”

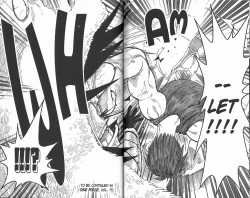

June 25th, 2010 Posted by david brothersI’m going to be completely honest for a minute here. My favorite genre isn’t crime. It’s “violence.” I like my violence stylish and casual. You can’t work that hard at it, unless you’re John McClane, and even he makes it look effortless. I’m talking about single bullet in the head, hard jerk, splash of blood on the sunglasses violence. We gotta kill every rat-bastard one of them violence. No-look pass violence, where the hand that holds the knife moves so quickly and smoothly it’s almost independent of the body. Fade to black, the tip of a cigarette goes bright orange, one gunshot, and that’s all she wrote violence. I’m talking about the fact that bullets cost about twenty cents a piece, so your life is much, much cheaper than you think it is.

My most recent fix for that is Keitaro Takahashi’s Jormungand. I’ve written about it before, but I think I spent a lot of time introducing it, rather than actually talking about it. Its premise is fairly simple, which is the weird part about the lengthy introduction I wrote. A child soldier who hates weapons joins an arms dealer and people die. That’s it. There’s subplots involving vain crushes and revenge and all, but that’s flavor.

The second volume ended with Jonah, the child soldier and theoretical focus of the series, going into a suicidal rage and attacking a man named Kasper, brother of his boss, Koko Hekmatyar. The first chapter of Jormungand volume 3 reveals why he hates him. Three months ago, in an unnamed country in West Asia, most likely Afghanistan, Jonah was sent to support a military unit. Present in the camp are a group of local orphans. Jonah befriends them and protects them. Halfway through that first chapter, a vile arms dealer takes two of the orphans and goes out looking for the US military ordnance that he was planning to turn into profit. When he accidentally triggers a landmine, he uses the body of Malka, a young girl, to shield himself. She dies. He doesn’t. Jonah has a very reasonable reaction.

“I can’t accept that Malka died and not that bastard. I’ll personally send him to hell.”

By the end of the chapter, every soldier in the base is dead and the the arms dealer has four new holes in his face.

Jormungand is primarily an action manga. Its primary focus is strictly on entertainment. Bullets are expended by the dozen, each member of the cast has their specialty (sniping, tech, knife fighting, alertness, a willingness to murder), there’s a hopeless romance, fanservice, goofy comedy, and a quirky/wacky character. With that said, it isn’t completely empty of meaningful content. Jormungand is about violence. It’s about the application of violence, its beauty, its ugliness, the way it twists and distorts people with its pressure. It’s about the necessity of violence.

After his… temper tantrum, Jonah becomes a bodyguard for Koko. He hates weapons, and the people who make and use them, due to the fact that his family was killed as a direct result of arms dealers prizing profit over basic human decency. Due to his situation, and his history, Jonah is sullen and withdrawn, and not at all eager to open up and soften his facade. Which, of course, means that people are eager to talk to him and they talk at him. The cast discusses weapons and violence with him a couple times in each volume. In volume two, Koko discusses the UN’s Millenium Development Goals with Jonah. She tells him that nearly two hundred countries pledged to raise twenty-two billion dollars to genuinely improve the world. She says, “But that figure was recently surpassed by the average annual amount of money spent on weapons in regional conflicts across the globe. Can you believe that? Clearly the world likes war a lot more than it likes little kids!”

She goes on to ask him who owns most of the guns in the world. Military? Police? Private militias? Terrorists? No. Civilians own sixty percent of all the guns in the world. Less than one percent are owned by radical militias. This PDF link to “Transition to Peace: Guns in Civilian Hands” suggests that her figures are accurate. Finally, Koko says, “It’s a world where it’s easier to find a gun… than to find kindness for a stranger.”

You know what I like in my action comics? Actual facts that are more depressing than anything in the world.

Violence and weapons, they’re like a genie that’s come out of its bottle. They are not going to go away. The best you can hope for is to minimize the damage. One thing that comes up again and again in Jormungand is what it takes to defend something. Koko is of the opinion that the guns, in and of themselves, hold no values. What matters is why you use them and what you believe in. Jonah is disgusted by weapons, period. They exist only to hurt and to kill. They took his family from him.

At the same time, the necessity of them drives a lot of his actions. He is in danger simply by existing, and especially due to who he associates with. He’s a bodyguard, and you can’t defend someone with pacifism. For Jonah, weapons are a necessary evil. He can’t escape them. He knows that he needs weapons to get the job done. Early in the first volume, Jonah and Koko have a one-sided conversation about killing arms dealers. “Can you really give up the gun?” Koko asks him. She answers for him, saying, “No, you can’t. You’ll never be able to walk away from weapons. You may hate them more than anyone… but you know better than most how powerful you are with a weapon in your hand.” Simply put: you can’t bring a knife to a gun fight, and every fight is a gun fight.

Lehm, the old thrill-seeking mercenary of the group, emphasizes the importance of a cool head. He tells Jonah that the violence they engage in is just business and that they do not get into feuds. Control is what separates the men from the boys. One kind of violence destroys both sides. With control, only one side goes down. When another man describes a gunfight as “symphony,” Lehm tells him that he’s wrong. A gunfight is “a farting contest. Something awful, ugly, messy, and most of all, shameful!” Lehm thinks that a gunfight should make you apologize, and, after killing a young woman, he does exactly that to a teammate. It was necessary to kill her to protect someone’s life, but Lehm regrets it regardless.

Valmet, the eyepatch-wearing knife-wielder, prizes efficiency and emotion over all else. She believes in doing just enough, and doing it for a good reason. She has a cartoonish crush on Koko, the kind that’s obvious to everyone but Koko, but it also means that she’s fiercely loyal. While she has a certain amount of flair, since this is an action comic after all, she’s very straightforward. No flourish, no tricks, just doing what needs to be done.

Mildo, a member of a rival group, considers Valmet the big man on campus and wants to make her rep by beating her. She provides a nice contrast to Valmet. She fights because, after a while, all of the violence and death makes you empty on the inside. You take up a gun to protect your family or fight for your country, but after a while, all of that just becomes a rationalization. Mildo does it because she wants to be the best.

I find Jormungand so interesting because there are all of these questions and motivations swirling around. Every character, including Jonah, acknowledges the fact that, at a certain point, violence is a necessary evil. Jonah knows that he can’t get justice without weapons. Koko has used her position as an arms dealer to gain a greater appreciation of the way the world works. Lehm is a mercenary because it’s exciting, but he knows how to control the more unpleasant aspects of it.

I don’t know if this is making any sense. I have this theory that the stuff people describe as mindless entertainment, or popcorn movies, or whatever–none of that is worthwhile. It’s the entertainment equivalent of treading water or ten cent ramen noodles. It’ll kill some time, and you won’t come out of it angry or anything, but it won’t make an impression, either. The stuff that people remember and talk about and genuinely enjoy tends to have something beyond lasers and cool fights. It’s got to have something for you to latch on to. Jormungand is an action comic with something to say. There’s a lot of action and several exciting gun battles, but between all of that are the conversations and arguments that give context to all of the violence. It’s kind of like having your cake and eating it, too.