Fort of Apocalypse: violence comix

July 2nd, 2014 Posted by david brothers

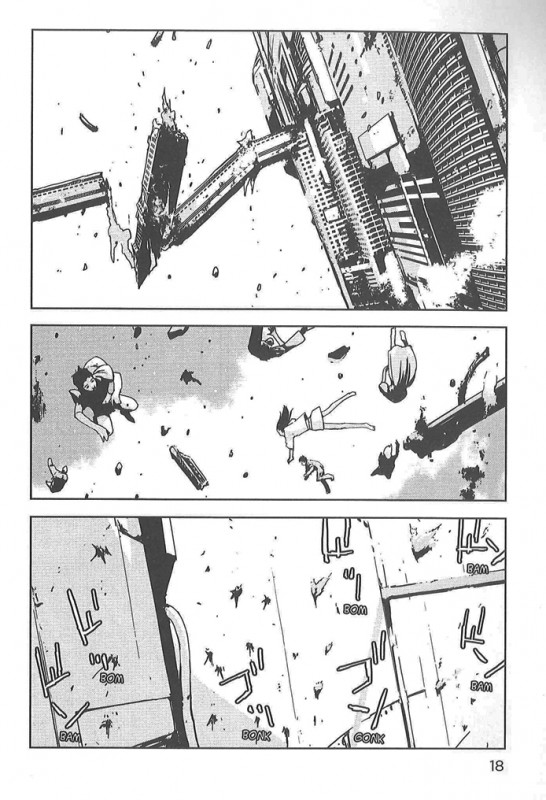

Fort of Apocalypse, written by Yuu Kuraishi and drawn by Kazu Inabe, isn’t that great. It’s serialized on Crunchyroll, and the hook is that it’s a horror manga with a zombie twist, mostly set in and around a Japanese juvenile detention center. It stars a group of boys who have to fight to survive in the school before being forced to fight for their lives as the world goes to hell. The problem is that it jettisons the most interesting aspects of that concept in favor of…bland twists, basically. It opens with a Nietzsche quote about gazing into the abyss, a painfully obvious move, and most characters are either borderline psychopathic, deranged, or totally cool with people doing deranged things on a regular basis. “You must be new here,” Fort of Apocalypse says. “Let’s start from the beginning.”

It’s endlessly derivative—or, being generous and disingenuous, “reminiscent”—of other, better, more popular works. Deadman Wonderland and The Walking Dead are the two most obvious touchstones for me, but there’s a bit of Highschool of the Dead and Lord of the Flies peeking in around the edges, too. Fort of Apocalypse lacks the ultra-fetishized hyper-sexuality of HotD, which has a weirdo carnival appeal/anti-appeal of its own, and instead goes for broke in another direction.

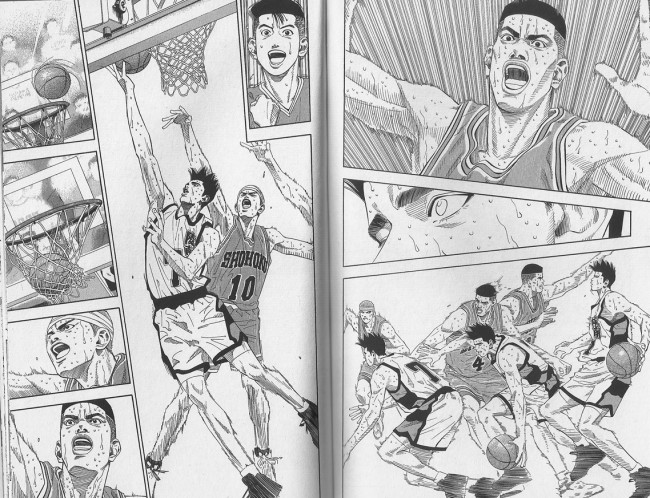

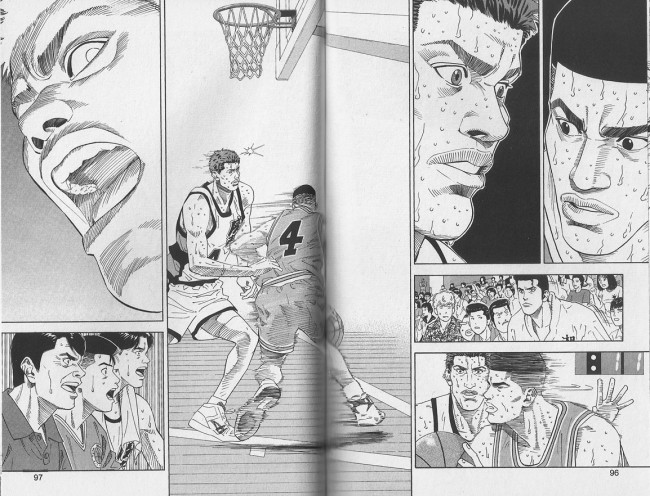

The art’s weird. It’s similar to a less stylish and stylized Dogs: Bullets & Carnage. It’s usually passable—not great, but good enough for a good panel here and there, and some good monster monster design and composition overall. Paired with the tone of the writing, Fort of Apocalypse feels seedy-but-familiar, a feel-bad comic that doesn’t actually make you feel bad at all but makes a big production out of going through the motions.

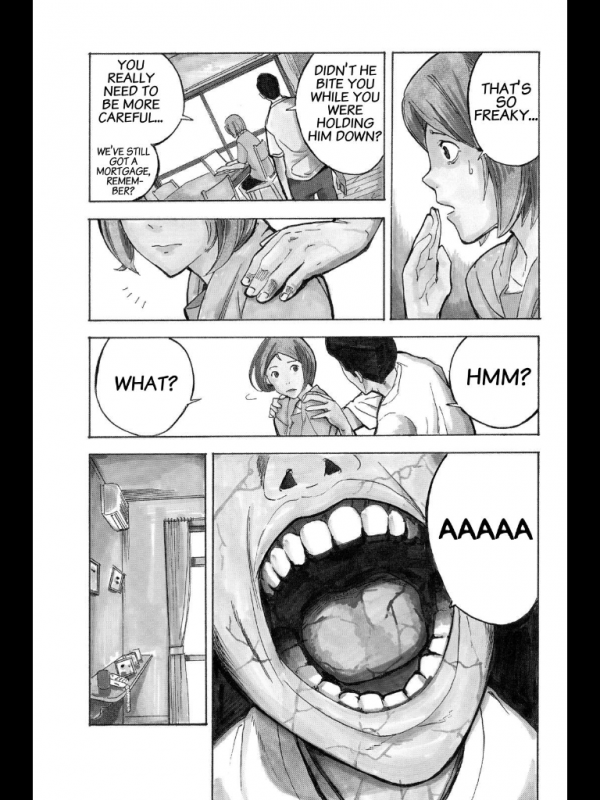

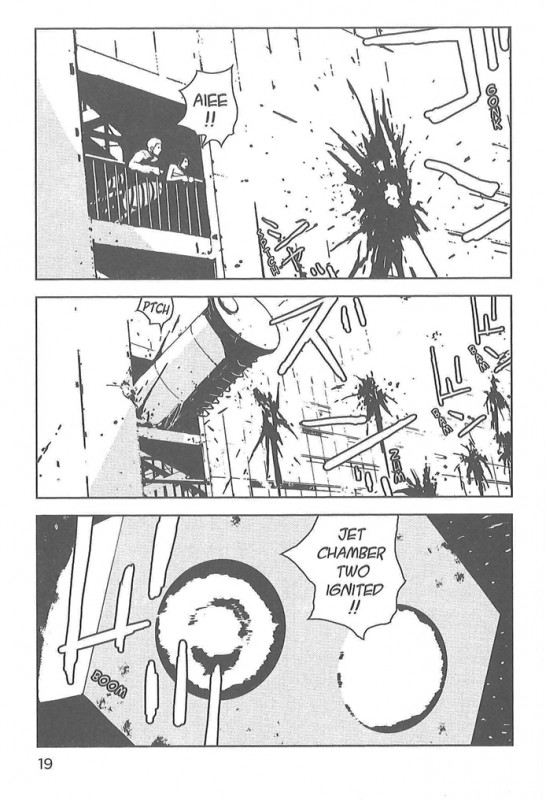

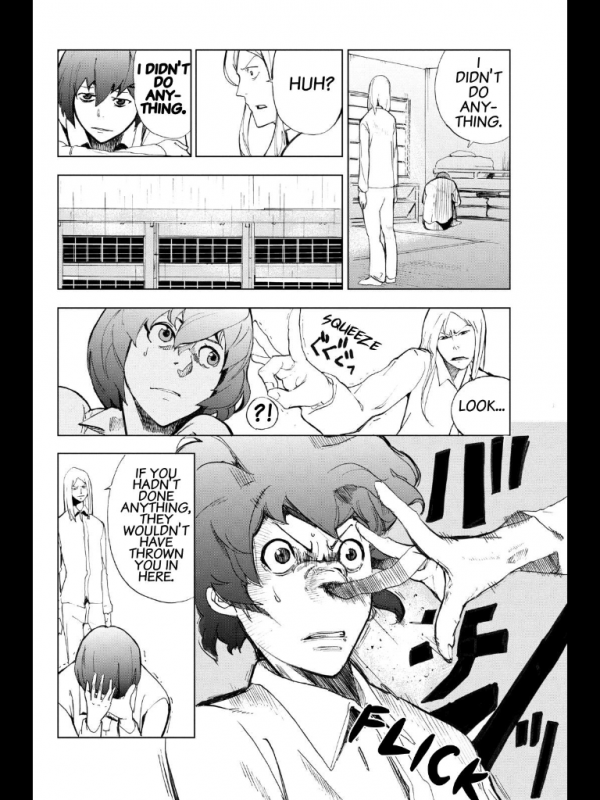

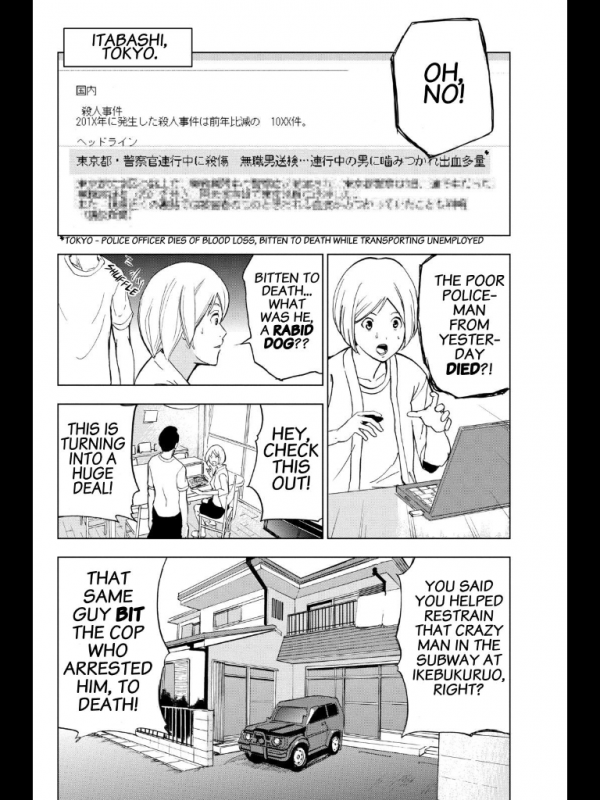

It’s not great, but it is lurid. One short scene:

Immediately before this moment in time, a different man in an irrelevant location sits up on his autopsy table, his back arched and general body language definitively inhuman. It’s an old trick—show the thing, then cut away to build tension or emphasize the spread of a sickness. The apocalypse is not coming. It is here.

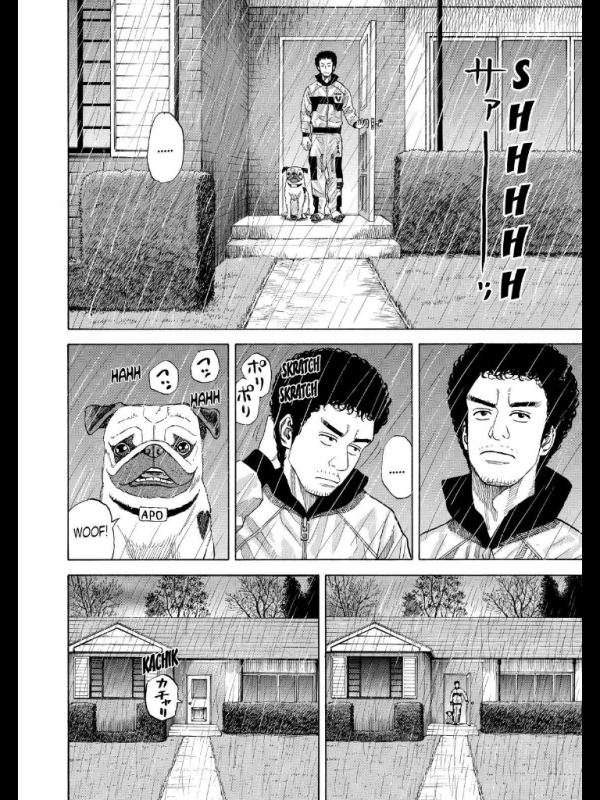

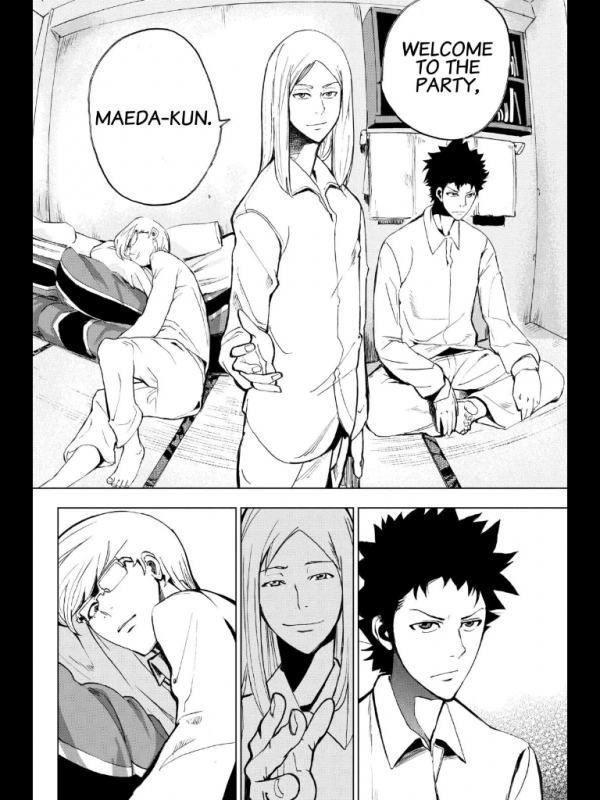

These characters are blanks, almost. Generic Husband and Generic Wife, unnamed and un-missed. They’re there to die, and while that isn’t remarkable (even the shot of the room to suggest unseen horrible violence is old and busted this time around), the next spread was:

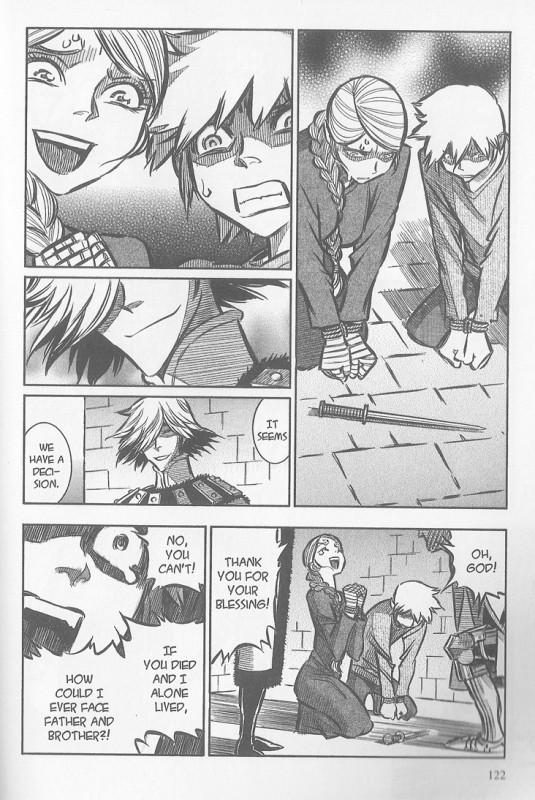

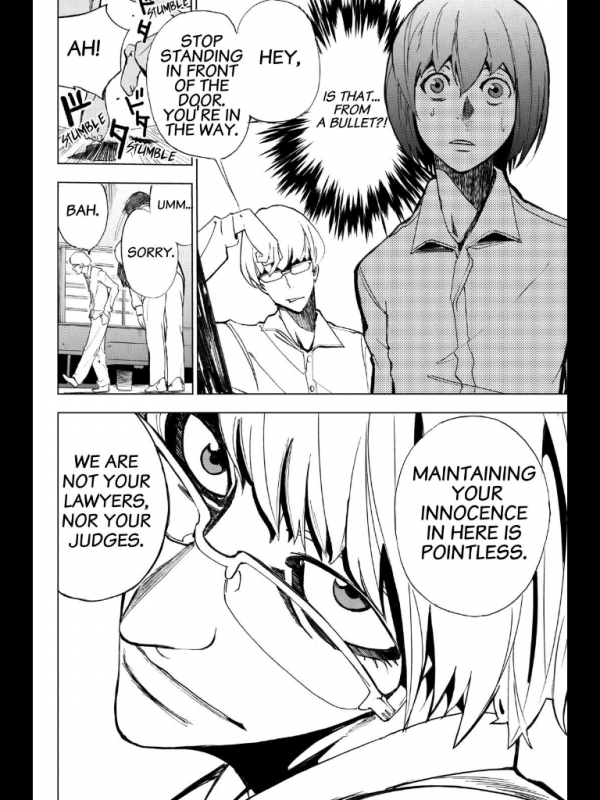

I was expecting a bunch of cuts away from the action to show the apocalypse rising, but I wasn’t being mean enough. A spread of the husband eating his probably-dismembered wife is bad enough, but what killed and grabbed me was the way the scene ends with a close-up of a family photo drawn by their kid, complete with an “I love you daddy!” inscription.

It’s one of those hilariously manipulative moves people pull sometimes, stacking up sad concepts like cordwood without putting in any work to make you believe in those concepts enough to feel bad about it. In better hands, this scene would be the ultimate betrayal. But Kuraishi and Inabe lean edgy, not poignant. I was struck by the meanness of that choice, the way it puts the idea in your head and then immediately moves on to the next one after your imagination fills in what happens next.

While the comic isn’t great, it’s got a mean edge that I enjoy. It’s sorta like the first season of The Following, the Kevin Bacon/James Purefoy serial killer cult thriller on FOX. That show is frequently trashy and incredibly poorly written. But it has a habit of going there that makes for good tv. Spearguns in diners, stabbings on subways, Edgar Allen Poe fetishists, and a conclave of serial killing English majors. A little “Can you believe this?” goes a long way. (Not that long, actually—season two doubled down on sad boring stubble dudes and I raced for the door before it was half-over.) It got me through a dozen volumes of Gantz, maybe even more. This isn’t Gantz on account of being nowhere near misanthropic and evil as that series, but it gets by.

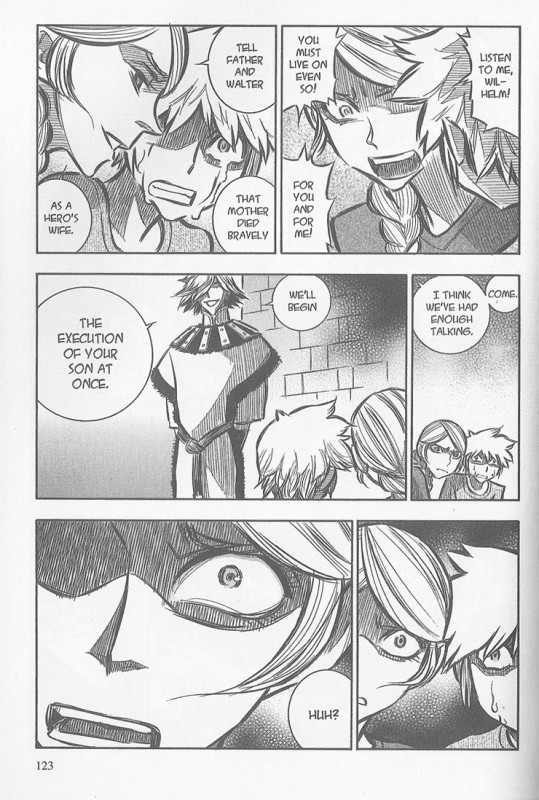

Fort of Apocalypse is lurid, but doesn’t feel cruel, even when a zombie grabs a teen’s upper and lower jaws and yanks them in opposite directions. Mitsuhisa Kuji’s Wolfsmund is real. She wants you to feel it, and it feels cruel. Fort of Apocalypse isn’t that. They want to show you outrageous things so you can go “yo, gross!” and then turn the page for more, and it turns out the best way to do that is to fill your comic with damaged and broken people who adjust to the end of the world by losing their minds.

I’m not sure how long I’ll last with Fort of Apocalypse, but it seems like once a volume, something outrageous enough to keep me interested happens. It goes there.