Tucker spent some time talking about how Panther’s Rage is about T’Challa’s failure as a leader

Tucker spent some time talking about how Panther’s Rage is about T’Challa’s failure as a leader. There’s a good reason for that: it’s the glue that holds

Panther’s Rage together. You can’t not talk about it.

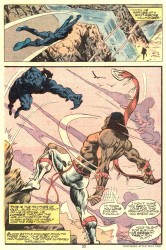

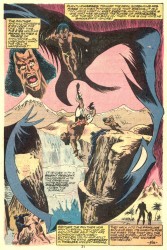

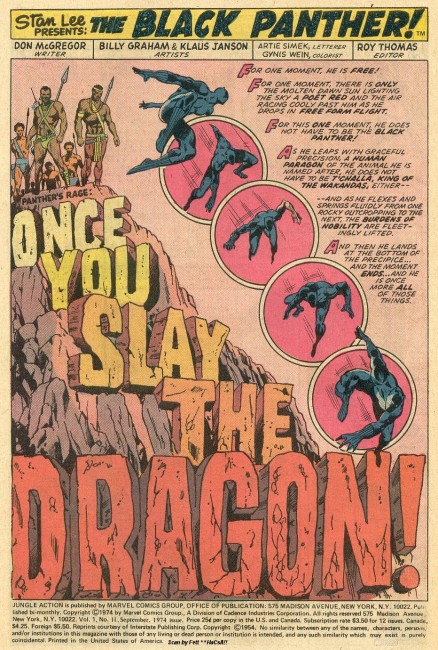

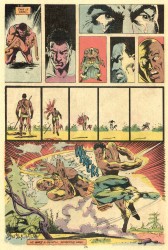

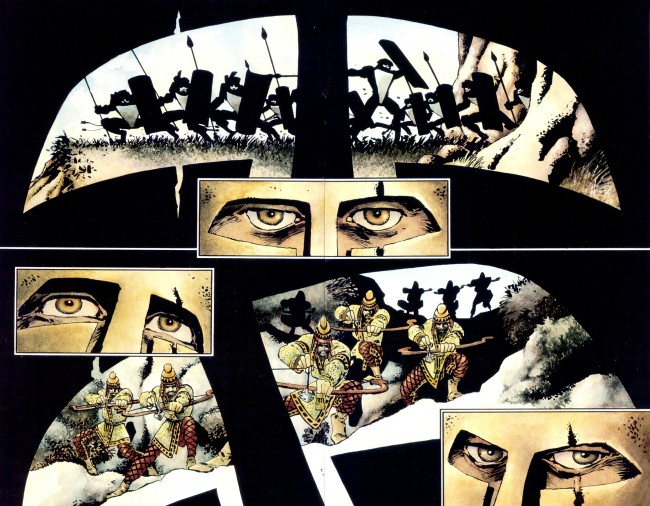

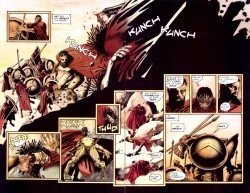

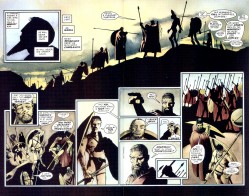

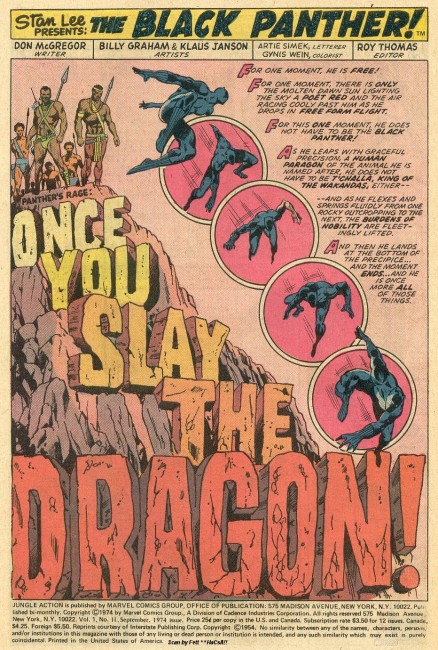

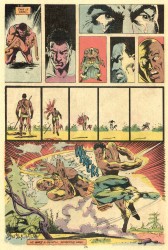

Except now that we’re fully into the story and all the preambles are out of the way, McGregor starts to stack the deck against T’Challa. In part four, the one drawn by Gil Kane, T’Challa wrestles a rhino to the ground to rescue a child. He kills the rhino in favor of the child’s life, which is a pointed statement in and of itself, I think, but the way in which he does it is what’s important. He wrestles the rhino to the ground and snaps its spine, something he learned by watching westerns. T’Challa’s buccaneering habits are learned. The Black Panther, with initial caps and constant swashbuckling, is an act. He saw them on tv, or read them in books, and have adopted them as his own.

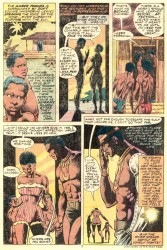

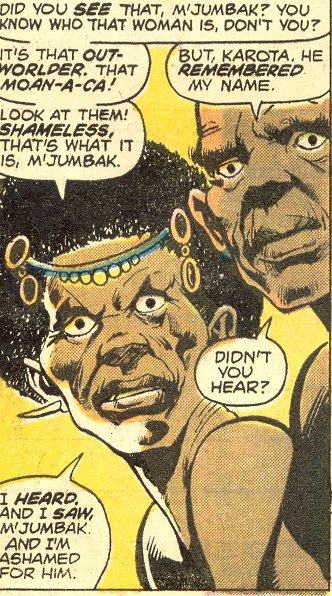

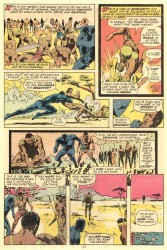

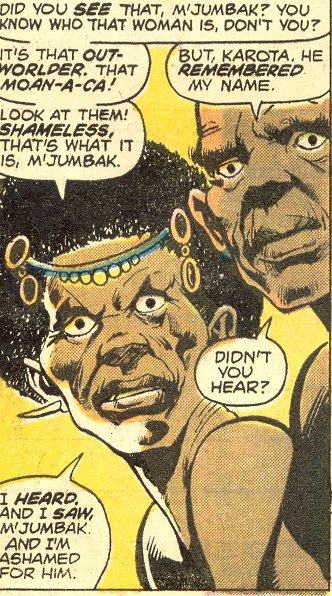

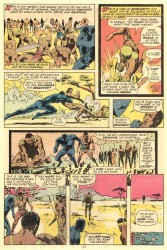

T’Challa easily and casually remembers the name of a farmer, stunning him. (Grant Morrison would use this technique thirty-some years later for Bruce Wayne in his run on Batman.) The farmer’s wife is unimpressed, focusing on his “outworlder” girlfriend. She sees the Americans he has emulated and the fact that he has brought back an American girlfriend, Monica Lynne. She feels the pain of desertion. Her husband feels the love of his king. Both are correct.

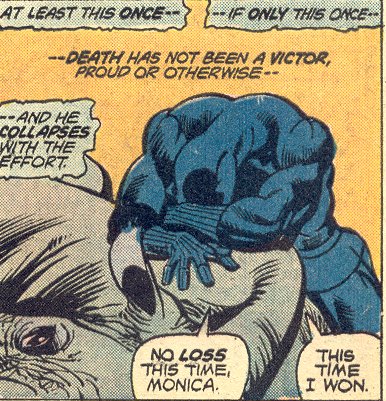

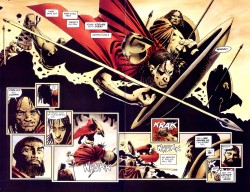

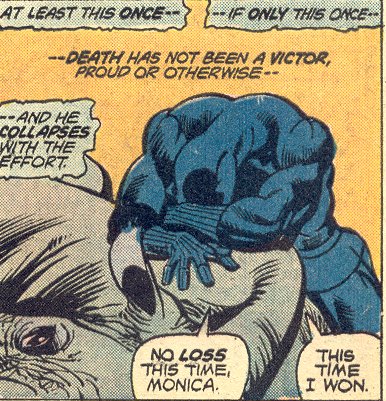

The conflict is easy to see, but McGregor doesn’t stop there. Before the farmer and his wife appear, Panther slumps over the rhino’s corpse and says, “No loss this time, Monica. This time I won.” He’s four issues into this story and he’s already cracking under the pressure.

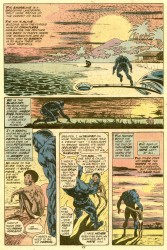

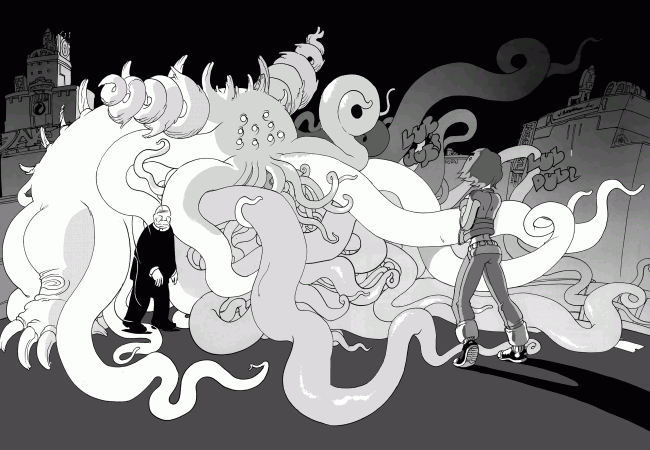

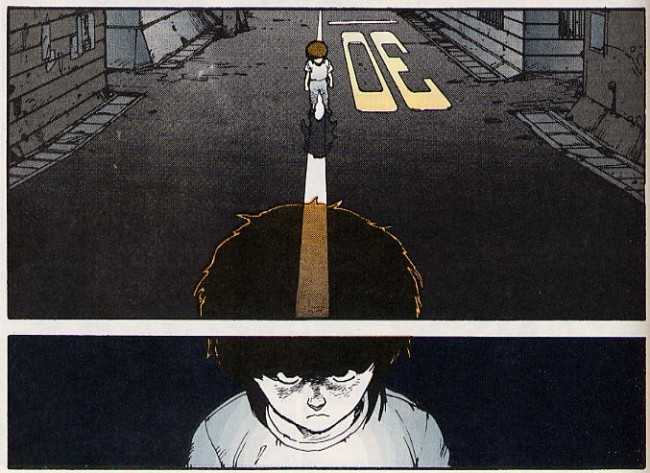

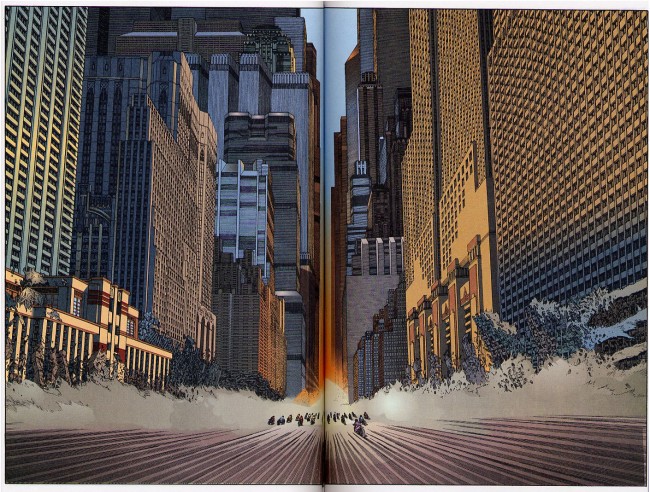

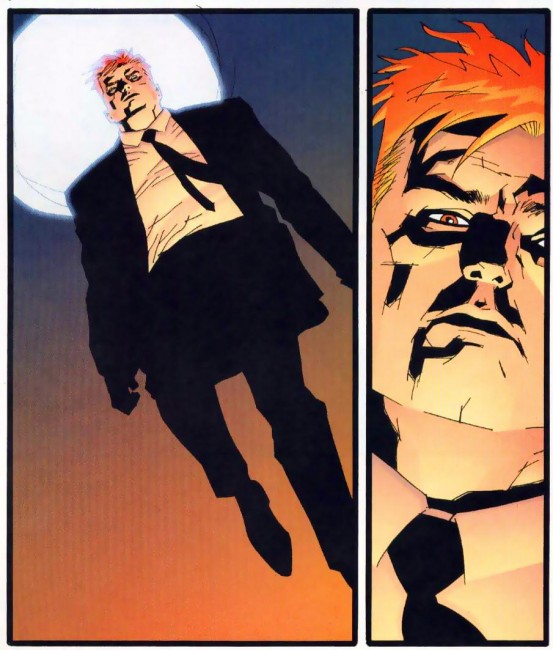

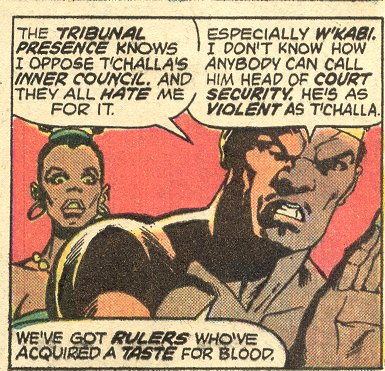

T’Challa’s constantly struggling, and not in the way that heroes struggle against villains. He’s fighting to not actually choose between American culture and Wakandan culture. He’s fighting to keep his kingdom, despite the fact that he left it behind at will in the past. He’s fighting to keep both Monica and W’Kabi. He’s fighting Killmonger and he’s fighting the results of his own swashbuckling. He wants it both ways, and even though he knows he can’t have it, he’s still fighting for it. He’s selfish. When the pressure becomes too much, what does he do? He goes to the river to brood alone, like a child.

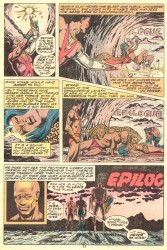

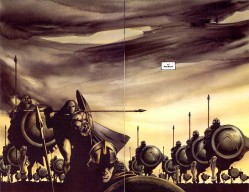

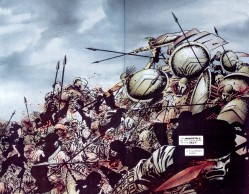

Panther’s battles manifest themselves in several ways over the course of Panther’s Rage. At the heart of each of them is the question of Wakanda versus America, in one way or another. Sometimes he outright fails. Sometimes he triumphs. He never actually wins, however. His victories are caked in loss.

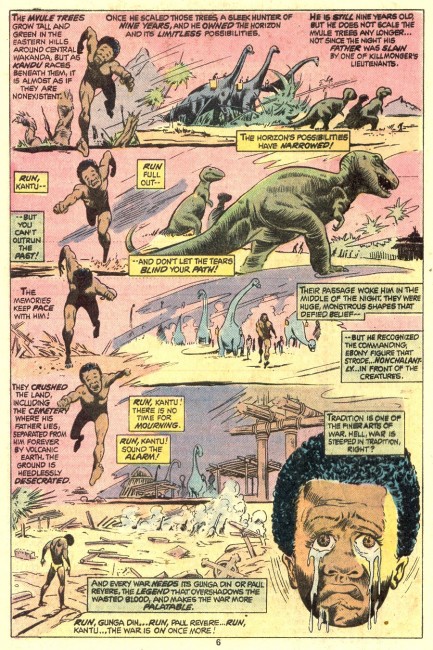

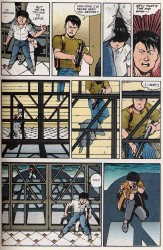

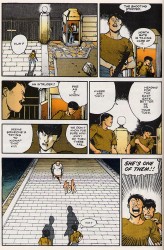

The farmer who T’Challa recognized was killed by zombies that very same night, leaving his wife and child alone. When the wife comes to the palace, requesting that the king go find her husband, T’Challa immediately goes to investigate. He runs afoul of those zombies and is beaten easily. He eventually escapes and runs back to the castle. He doesn’t win. He doesn’t even retrieve the farmer’s body. In fact, the farmer’s body sits there, baking in the sun, until the next night when T’Challa gets his nerve up to go back to the graveyard. The wife doesn’t find out that her husband is dead until later because T’Challa is preoccupied with his own problems. Result: failure.

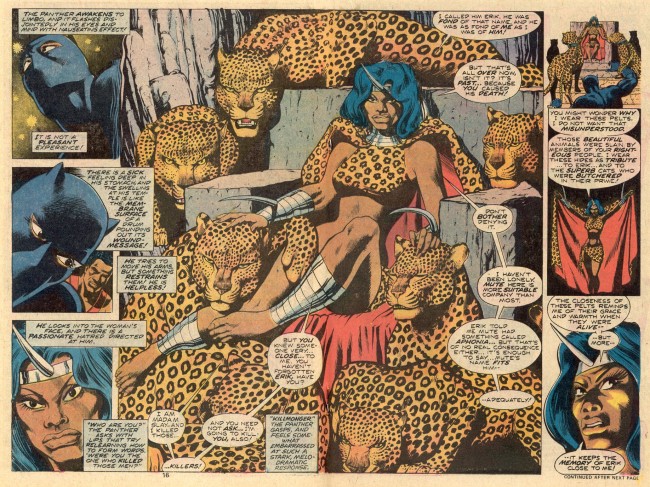

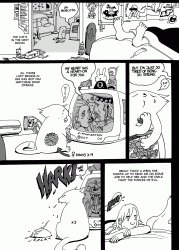

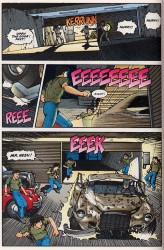

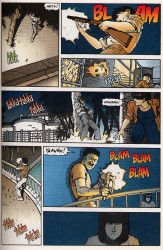

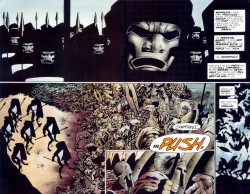

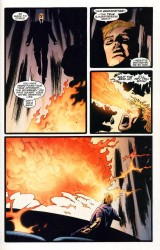

Yes, there are zombies and monsters in Panther’s Prey. The villains have names like Baron Macabre and Lord Karnaj. Yes, their names are goofy and stupid, about as generically superheroic as you can get. Except: Macabre is a mask, someone playing a role. Karnaj emphasizes that Erik Killmonger, the villain behind the villains, gave him that name. The zombies are rebels, dressed up with fake talons and ghoulish makeup.

This is Killmonger’s plan, and it’s a doozy. He’s using T’Challa’s language, superheroes and faked up gimmicks, to terrorize Wakanda. He’s playing on the superstitions of the populace to get the job done, and he’s using the very thing T’Challa deserted Wakanda for to do it. It’s America vs Wakanda, but viewed through a twisted mirror.

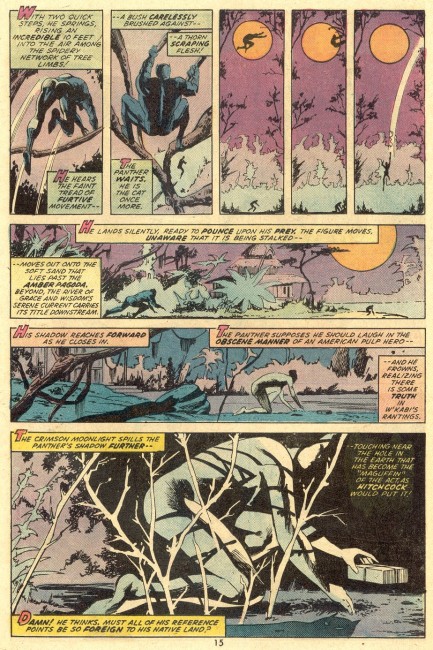

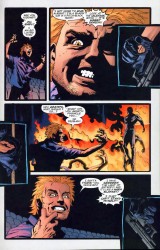

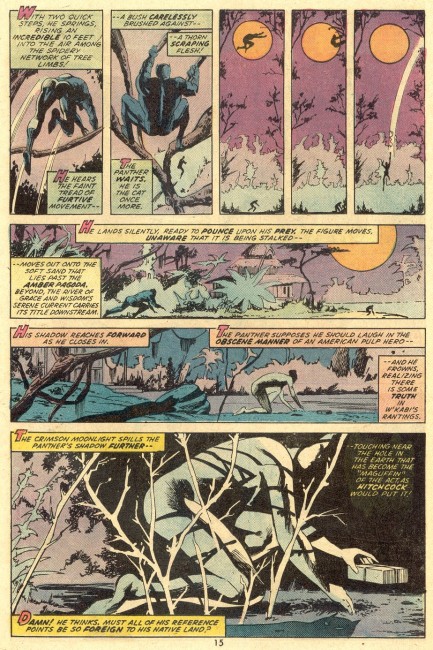

Monica is accused of murder partway through these chapters and exonerated in the final one. Just before proving Monica’s innocence, T’Challa approaches his prey and idly makes a reference to Alfred Hitchcock in his thoughts. “Damn! he thinks. Must all of his reference points be so foreign to his native land?” Wakanda attacked his American woman, and even in the middle of that, he’s fighting Wakanda vs America on the inside.

Panther’s Rage puts me in mind of Ann Nocenti and John Romita, Jr’s run on Daredevil, where every act of violence was a sign of Daredevil’s shortcomings as a hero. A hero can solve problems without making mistakes and without anyone getting hurt. T’Challa, however, has already made his mistakes, and now the only thing that’s left is the pain.

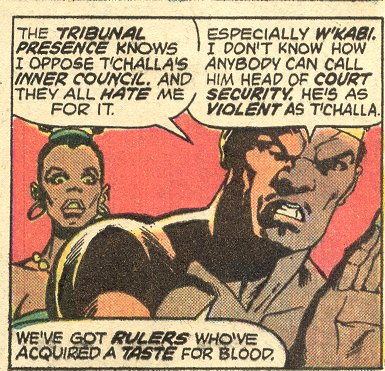

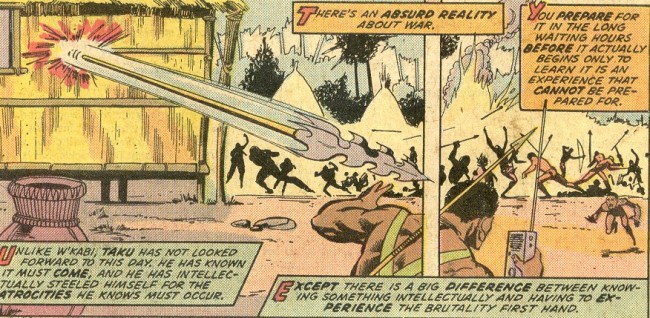

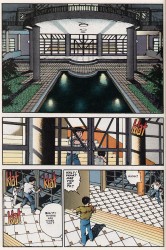

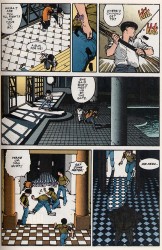

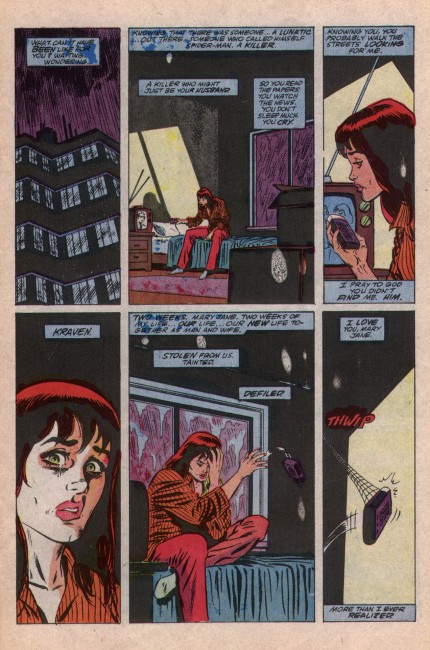

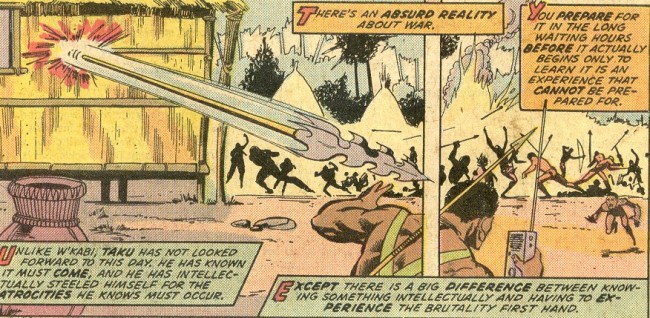

What’s sad about that is that T’Challa won’t be the focus for all of the pain. The farmer dies and his wife and son suffer. Monica is harassed and imprisoned. W’Kabi has lost faith in his king. Wakanda is being battered by Killmonger’s Death Regiment. Taku, T’Challa’s good friend and a definite pacifist, is forever tainted when he experiences the horrors of the war against Killmonger firsthand.

T’Challa? Some people just kind of point out how much he’s screwed up and he gets beaten up every once and a while. These three chapters lay the consequences for his actions on everyone but T’Challa, which in turn serves to increase his burden. Everyone around T’Challa ends up twisted and distorted by the pressure of the situation. Monica is miserable. W’Kabi is furious. Taku is understanding, but even he’s losing his patience. This is T’Challa’s fault.

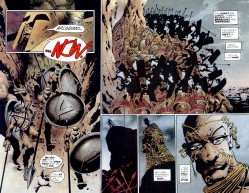

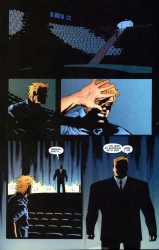

Taku is the saddest casualty of this war, for my money. He’s quiet and sensible, seeking only to help where he can. The narration describes him as a man who “listens instead of inflicting his personality upon others.” Despite this, he’s not afraid to call T’Challa out on his crap. When T’Challa is pulling his ‘woe is me’ act beside a river, Taku sits beside him and they speak. T’Challa laments the fact that he has lost W’Kabi, and Taku says, “Part of it is Killmonger. Surely you know that?” T’Challa, clearly misreading Taku, goes off on how Killmonger only wants to govern Wakanda according to his own desires. Taku, though, brings the ether and asks T’Challa if he has been any different.

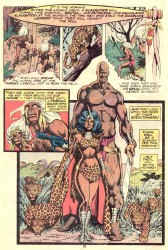

Taku befriended Venomm, a villain from chapters one through three, and refers to him by his first name, Horatio. While Venomm did side against Wakanda, he is still a human being, and Taku manages to pull that out. When it comes time to strike back against Killmonger, Taku must betray his friend. When he expresses that thought, W’Kabi reacts with shock. What betrayal? They don’t owe Venomm anything. Taku knows the truth, though. He says that by betraying “a confidence,” he has “betrayed [himself] as well.” Being true to yourself means being true to yourself at all times. Bending your rules just shows how little you believed in those rules. Taku is a man of integrity, and T’Challa’s actions have forced him to break with that integrity in a way that he is not comfortable with.

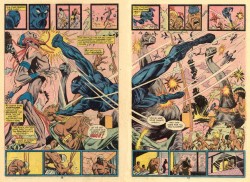

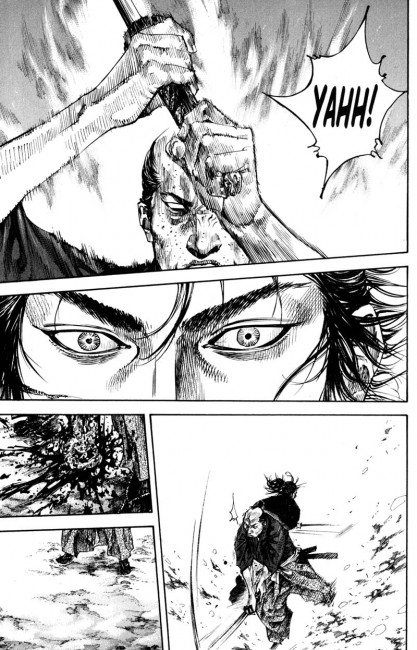

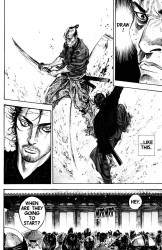

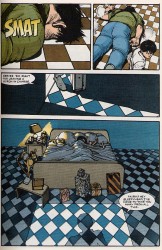

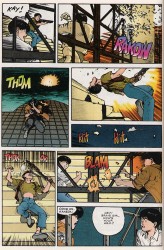

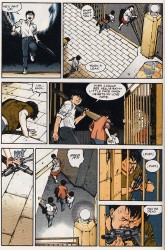

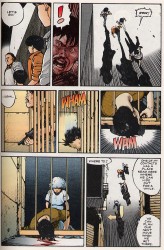

While W’Kabi is eager to do battle against Killmonger, Taku simply did the best he could to intellectually prepare for it. It didn’t work. When Lord Karnaj kills a child as a side effect of trying to kill Panther, Taku loses it. In a killer and mostly silent Billy Graham page, Taku approaches Karnaj, shrugging off two sonic blasts. He drops his spear, because certain jobs just require the satisfaction of working with your hands. He beats Karnaj near to death, ranting at him all the while, before Panther stops him. Even W’Kabi, who believes that everything that Killmonger’s lackeys get is what they deserve, is troubled by this new change.

I feel like there weren’t a lot of superhero comics working in this mode back then. You can trace every terrible thing that happens in Panther’s Rage can be easily traced back to T’Challa’s betrayal, which places a certain measure of responsibility on his shoulders for the entire situation. Amazing Spider-Man flirted with it during the death of Gwen Stacy storyline for about three pages and a half (also in 1973), and Green Lantern had the hamfisted “What about the brown skins, Mr. Charlie?” scene, but this is an extended takedown of a hero and a deconstruction of him at the same time.

McGregor, Graham, and Buckler are going hard at who T’Challa is and what he represents, and the result is a story where the superhero doesn’t look so superheroic any more.

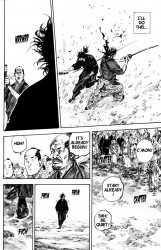

Next is Tucker, with parts seven, eight, and nine. It’s got a winter wonderland, dragons, and marital strife.

, Batman and Robin 2: Batman vs. Robin