The first all-black comic was 1947’s All-Negro Comics. Everything I know about it I read from this site. It’s a somewhat lengthy read, but well worth your time.

All-Negro Comics once attempted to be a representative and standard-bearer for an entire race. The situation was so off-center and dire that an attempt to educate both blacks and whites as to the history and prestige of the black race was seen as necessary. I transcribed the introduction that Orrin C Evans wrote, because I find it pretty fascinating.

Dear readers: This is the first issue of All-Negro Comics, jam-packed with fast action, African adventure, good clean humor and fantasy.

Every brush stroke and pen line in the drawings on these pages are by Negro artists. And each drawing is an original; that is, none has been published ANYWHERE before. This publication is another milestone in the splendid history of Negro journalism.

All-Negro Comics will not only give Negro artists an opportunity to gainfully use their talents, but it will glory Negro historical achievements.

Through Ace Harlem, we hope dramatically to point up the outstanding contributions of thousands of fearless, intelligent Negro police officers engaged in a constant fight against crime throughout the United States.

Through Lion Man and Bubba, it is our hope to give American Negroes a reflection of their natural spirit of adventure and a finer appreciation of their African heritage.

And through Sugarfoot and Snakeoil, we hope to recapture the almost lost humor of the loveable wandering Negro minstrel of the past.

Finally, Dew Dillies will give all of us–young and old–an opportunity to romp through a delightly, almost fairy-like land of make-believe.

And we’re proud, too, of our big educational feature–a monthly historical calendar on which the contributions of the Negro to world history will be set forth in each issue.

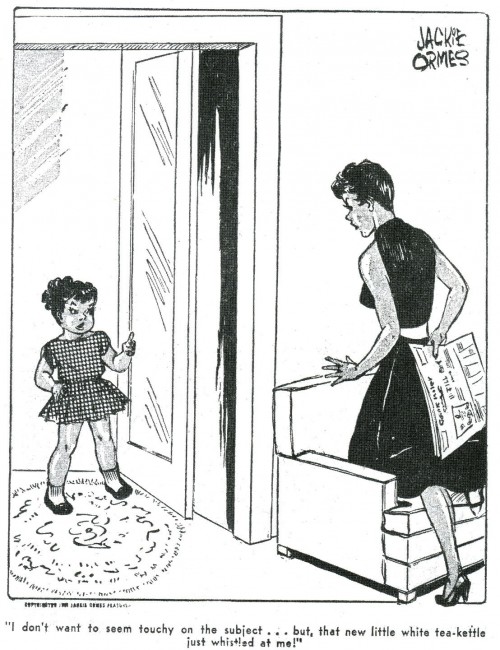

What’s important about All-Negro Comics is that it is an answer to a trend in comics. A conscious answer, one calculated to present something that hadn’t, to my knowledge, been properly represented in comics. In mainstream comics at this point, Whitewash from the Young Allies and Will Eisner’s Ebony White were par for the course. Clumsy, bumbling racial caricatures were, as near as I can tell, the norm and accepted by polite society. Will Eisner himself accepted that White was a racial stereotype with an excuse that boils down to “it was funny back then.”

All-Negro Comics, then, was a shot across the bow of pop culture racism. It is counter-programming against the cultural politics of the era it was written in. It puts the lie to the flimsy excuse of “It was just a product of its time.” Accepting that excuse means assuming the worst about the people of that time, that they were okay with denigrating and marginalizing an entire culture. It reminds me of the saying about how all evil needs to triumph is for good men to do nothing. At the same time, if you’re doing nothing, are you really that good?

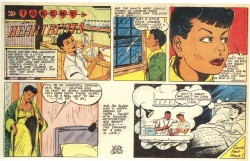

Evans’s opening editorial begins combat against the idea of the shiftless, lazy Negro. It introduces Ace Harlem, a positive black role model intended to represent the modern black male. Ace Harlem was cast in the same mold as Dick Tracy or The Spirit- an upstanding man out to do good simply because it was the right thing to do.

There’s a message implicit there. Ace looked out for his people, tried to do the right thing, and was specifically intended to represent the black community. As near as I can tell, he was created to be what we often mistakenly assume a lot of black characters to be nowadays: a representative for the community at large, rather than a specific person. The existence of Ace meant that black people, just like whites, weren’t born criminals or inferior. They had just as much drive, just as much of a sense of justice, as anyone else did.

Ace Harlem says what everyone should have known already, is what I’m saying.

All-Negro Comics puts me in mind of Spike Lee and, more recently, Tyler Perry. Spike has a rep for being a loudmouth jerk, but he’s a guy who also aggressively pushed a very specific agenda: movies should reflect real life. Sometimes this meant a majority white cast and sometimes this meant majority black. He wanted to show that, at the heart of things, we’re all the same. If you look at the casts of his movies over the years, his track record reflects that. He saw a gap and he worked to fill it.

Tyler Perry, on the other hand, saw a different gap. He saw that no one was really marketing movies to black women and leapt upon it. He pounded out cheap movies aimed at that demographic and look at that– little old black ladies hit the movies in droves, bringing half the church with them, and Tyler Perry sleeps on a mattress made out of dollar bills.

Between then and now, there was a hole in comics. All-Negro Comics, like Spike Lee and Tyler Perry, attempted to patch that hole. It lasted long enough for only the one issue, but it shows that the thirst was there. Someone recognized the hole and attempted to fill it.

That market is out there. Black people, just like everyone else, will read comics. Black people will make comics. Black people are doing both. Where All-Negro Comics was meant to be counter-programming in 1947, what we have now is even better. Take a stroll down artist’s alley at your local convention. There are black creators doing their thing in a variety of genres and styles.

The rise of the internet, graphic novels in bookstores, and affordable print on demand turned black comics (for whatever definition of “black comics” you’re using) from something with a niche appeal into something that can genuinely be considered a success. You can buy Aya at the same place you buy your Stephen King novels, you can read World of Hurt or Ants on your lunch break, or you can order Ho Che Anderson’s King off Amazon and have it the next day.

Things are better than they were before. We don’t need one single comic to represent the fact that black people, like white people, are human beings. I’d rather that the mainstream comics didn’t marginalize or exclude their black fans and characters, but you know what? Comics has plenty of Spike Lees and Tyler Perrys. I don’t have to beg Mark Millar for table scraps when Dwayne McDuffie is ready and willing to provide a full course meal.