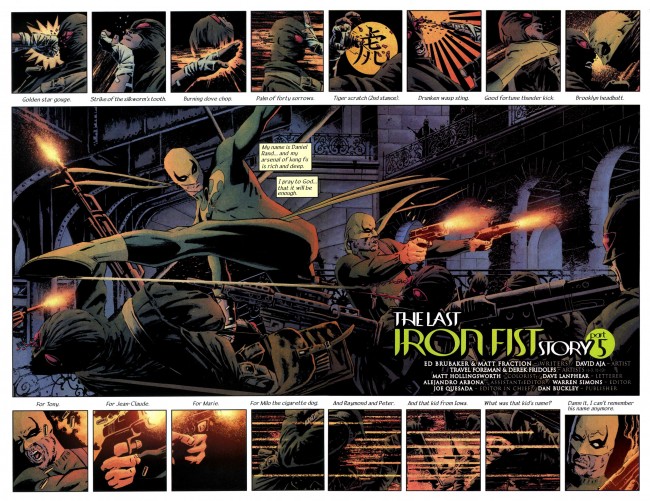

7 Artists: David Aja

July 8th, 2010 Posted by david brothers

There’s this Grant Morrison quote I like a lot. It’s inflammatory, but I think there’s a lot of truth in it.

As for all this talk I keep hearing about how ‘ordinary people’ can’t handle the weird layouts in comics – well, time for another micro-rant, but that’s like your granddad saying he can’t handle all the scary, fast-moving information on Top of the Pops and there’s really only one answer. Fuck off, granddad. If you’re too stupid to read a comic page, you shouldn’t be trying to read comic books and probably don’t. As creative people, I feel we need to call time on the relentless watering down of comics design and storytelling possibilities in some misguided attempt to appeal to people who WILL NEVER BE INTERESTED in looking at or buying hand-drawn superhero comic books.

The emphasis is mine, and keep it in mind as you read.

How do you read a comics page?

Stupid question, right? But no, not really. The comics page is the most basic building block of a comic book. They haven’t changed too much since they were first invented. You can have words and pictures and you can have ink in CMYK or digital PSDs or AIs in RGB, but without a page to put it on, the tabula rasa of yore, you’re out of luck. It’s probably the one thing in comics that’s genuinely indispensable. (Well, that and ink.)

You could make cases for Jack Kirby, Steranko, and even the often-horrid art of the speculator boom of the ’90s for changing the way people read comics. This change has happened several times. The change came when people began treating the space between the panels, the passage of time that happens there, differently. Panels began to convey different kinds of action.

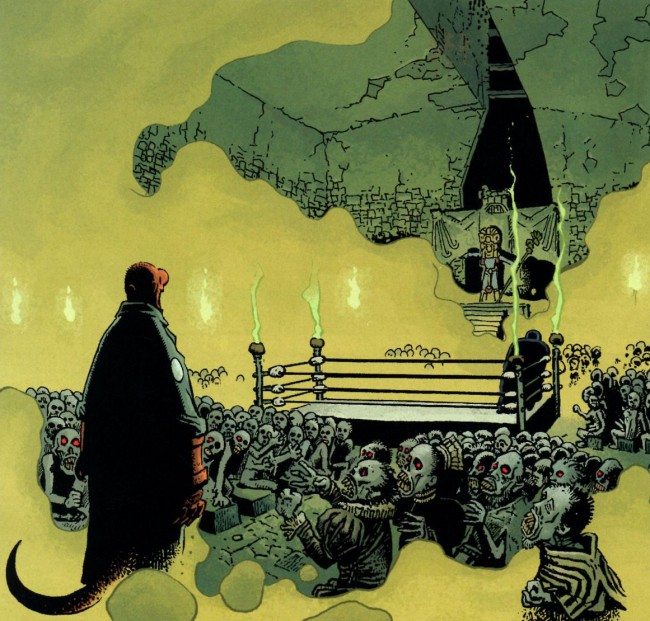

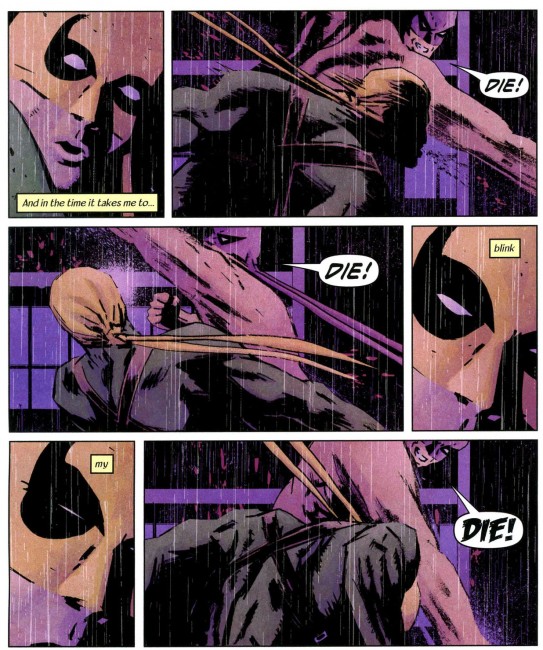

What’s nice about David Aja’s work is how he treats his layouts. Rather than simply being a tool to convey the story, which is generally how most artists treat their layouts, Aja often turns the layout into part of the story. It’s like if the television you use to watch movies ended up actually introducing new data into your viewing experience.

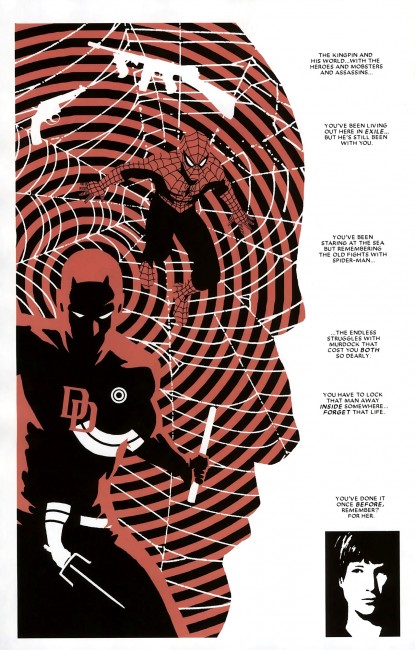

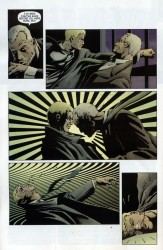

He’s done this in a variety of ways. David Uzumeri wrote a pretty fantastic appreciation of a single page from Daredevil 116 for Funnybook Babylon. It’s absolutely worth reading, if you have the time. The reason why this page is so crucial is simple. (Hopefully I can talk about it without plagiarizing David.) The Kingpin is a man defined by his relationships. The tommy gun and revolver represent his status in a very old-fashioned form of organized crime. Spider-Man was his introduction to the superhero community. Daredevil looms large in Kingpin’s mind, ready for violence, but bottled within Daredevil is a silhouette of Bullseye, Daredevil’s worst enemy and Kingpin’s former chief assassin. Separate from all of that is Vanessa, the Kingpin’s wife. He tried to keep her segregated from his less than savory pursuits, but those pursuits eventually destroyed her.

(When Ditko and Romita would draw Spider-Man with a half-Spidey mask over his face, it was meant to show how Spider-Man and Peter Parker coexisted, and how they cooperated and interfered with each other’s lives. They compete and battle each other, with Spider-Man taking the form of his responsibility and Peter Parker being his inner selfishness. The two halves need each other. They define each other by their existence, and sometimes even their absence. A simple technique–a face that is half Peter Parker and half Spider-Man–with fantastic depth. It’s storytelling quicksand, you don’t realize just how deep it goes til you’re knee deep in it. If that technique went off and had a baby with Steranko’s Agent of SHIELD, and that baby was raised by some of the more out there Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli stuff on Daredevil, you’d end up with something like this, I think. This is also a technique that only works in comics. It’d look stupid in live action.)

This is a comics page. It’s the same kind of comics page you’ve grown up reading, but it isn’t. The grid is gone, replaced with the outline of a man’s head, and stacked high with meaning. It’s part of the story, not the hanger the story is draped upon.

Next.

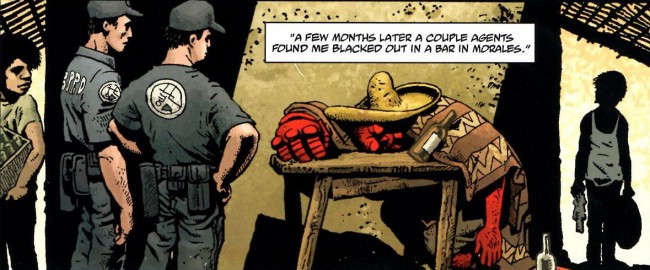

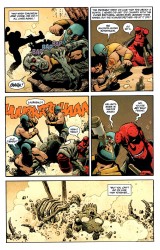

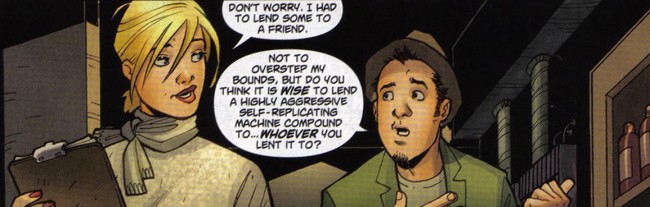

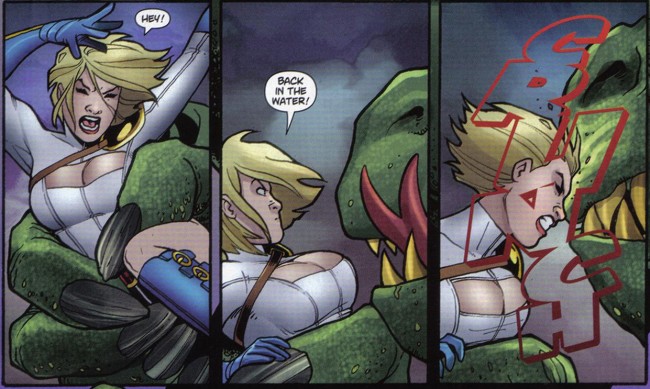

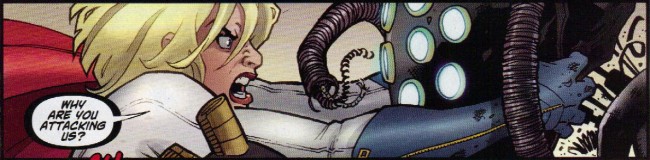

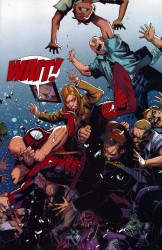

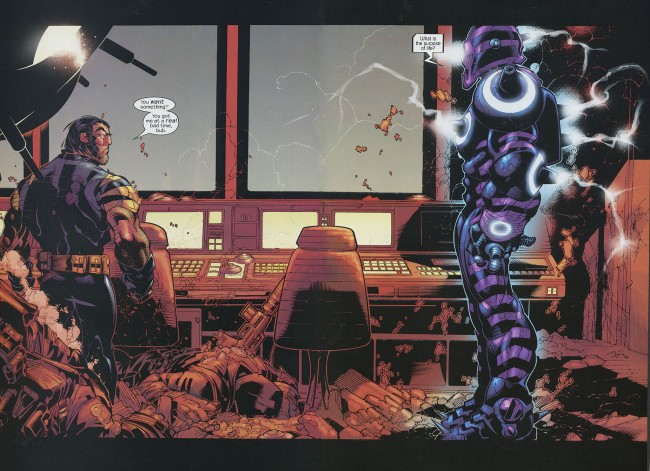

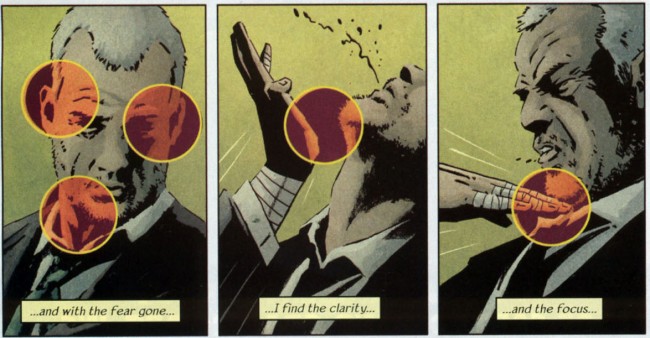

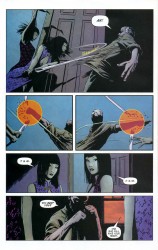

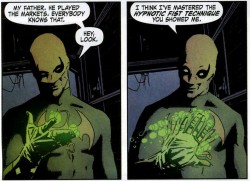

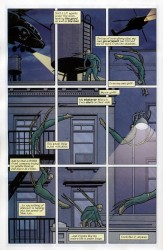

In Immortal Iron Fist, certain punches and strikes get a bit of extra oomph. Aja plays with your sense of time to accomplish this. Each panel on a page is a specific instant in time. When Spider-Man has several afterimages present on a page, doing a diverse array of actions (or just punching one guy 3-10 times), that is meant to take place in the same instant. It’s a show of speed. Aja, though, slams it into reverse and likes to pull your focus in to a specific point on the page you’re reading.

You see the punch in a panel of its own, but there’s a little more added into the mix. Small circles, like targeting reticles in video games, emphasize the point of impact, and by virtue of taking place at one specific moment in time, emphasize the impact itself. It changes the pace of your reading, so instead of going punch-kick-punch-uppercut, you’re seeing punch-jawbone-kick-kidney-punch-neck-uppercut-chin. Four beats become eight, and suddenly you’ve spent more time on the panels, more time focusing on the thing the layout wants you to focus on, than you normally would have. One breath becomes an infinite amount of time, captured like a slideshow.

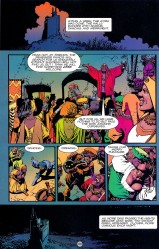

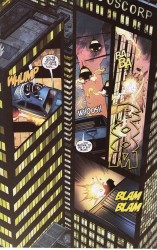

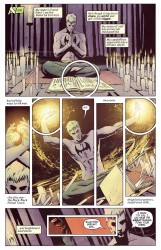

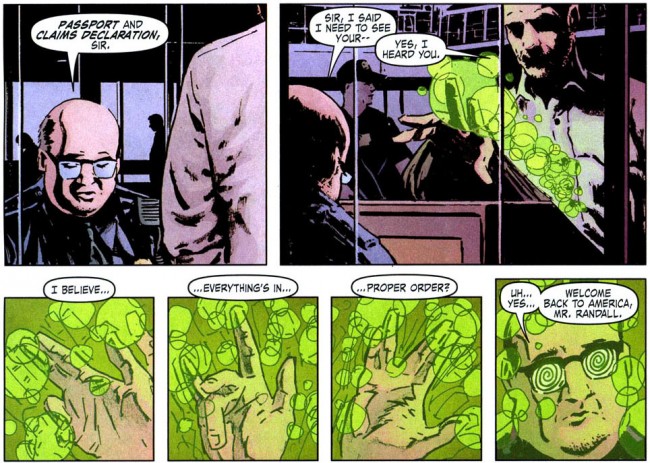

He does something else when Orson Randall arrives in the USA. He does a little jedi mind trick, something that would be a flick of the wrist and a blur of the fingers in real life, and each position of his hand gets a panel dedicated to it. This little bit of nothing, something that later in the book is a mere blur across two panels, gets a lot of page space.

He does something else when Orson Randall arrives in the USA. He does a little jedi mind trick, something that would be a flick of the wrist and a blur of the fingers in real life, and each position of his hand gets a panel dedicated to it. This little bit of nothing, something that later in the book is a mere blur across two panels, gets a lot of page space.

This forces you to dwell on the trick itself, rather than the fact that a trick happened. Imagine if Spider-Man’s web-swinging was drawn differently. Spider-Man in mid-air-right arm curved in-right arm flung out-thwip position-web shooting out-hand pulling tight over the web-right arm pulling back and propelling Spider-Man forward. One action split into seven distinct segments. This is choreography at work.

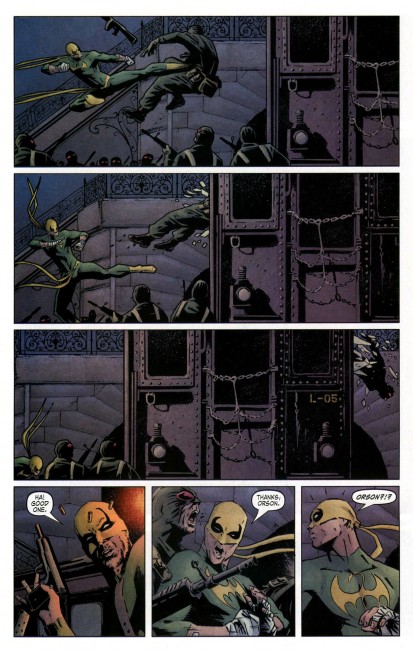

These are all magic tricks that artists can use to control how you read comics. Aja does it better than most, particularly on Iron Fist. Two things made kung-fu movies exciting: speed and clarity. You want to see people moving quickly and doing impossible things, but you also want to be able to see exactly what Five Elements kung-fu is. If you can’t tell what it is, the action sucks (see also: The Dark Knight). Iron Fist is a kung-fu book, and while the cinematic stylings of kung-fu movies cannot be directly transplanted onto a comics page, Aja does the next best thing. He captures the look and the feel, if not the totality of the motion.

Do you get it?

A punch, for a particularly relevant example, is one smooth motion with a lot of moving parts. Your back muscles flex, your arm changes shape, and your body turns with the punch. Throwing repeated punches turns one motion into many, but since they’re taking place on the same body, they have to flow into each other. It’s not as easy as just drawing jab-jab-straight. Look at this Roy Jones Jr highlight reel. Jones is fantastically flashy, but watch how he moves. His legs move, his feet shift, his head bobs, and his body works. Have you ever seen Bruce Lee’s Green Hornet audition video? There’s a lot of similar things on display, and the theory holds true for all of it. Aja applies this sort of thing to comics very well, showing the myriad motions that people go through when they do simple or complex things and picking out the specific moments you need to show maximum action.

This is the opposite of the watering down that Morrison spoke out against. It’s aggressively pushing forward the standards of what to do with a comics page, how to tell a story, and expanding the language of comics.

And I haven’t even talked about his collaboration with Ann Nocenti, 3 Jacks. Tim O’Neil and Abhay already did that.

Pay attention to David Aja. Pay attention to how you read comic books. Everything matters. It’s all part of the story. And if you can’t handle it… maybe you should quit comics and start reading novels.