Screw Music: Cocaine Pentagrams and the Twerk Team at a Black Mass

February 17th, 2012 Posted by david brothersThe Damon Albarn Appreciation Society is an ongoing series of focused observations, conversations, and thoughts about music. This is the fifteenth. I realized I had a lot of screw music in the official rotation. It’s a type of music I like a lot, but find it hard to articulate why. There’s a good reason for that, I think. I keep going to a few key words, though–it sounds evil, it sounds wrong, it sounds off, it sounds abstract, it sounds sideways, it sounds like Hell… it sounds great. It’s just that whenever those monks get around to updating the Ars Goetia, they’ll have to add a footnote that King Paimon is the patron demon of screw music.

Minutes from previous meetings of the Society: The Beatles – “Eleanor Rigby”, Tupac – Makaveli, Blur – 13 (with Graeme McMillan), Blur – Think Tank (with Graeme McMillan), Black Thought x Rakim: “Hip-Hop, you the love of my life”, Wu-Tang Clan – Enter The Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), On why I buy vinyl sometimes, on songs about places, Mellowhype’s Blackendwhite, a general post on punk, a snapshot of what I’m listening to, on Black Thought blacking out on “75 Bars”, how I got into The Roots, on Betty Wright and strong songs

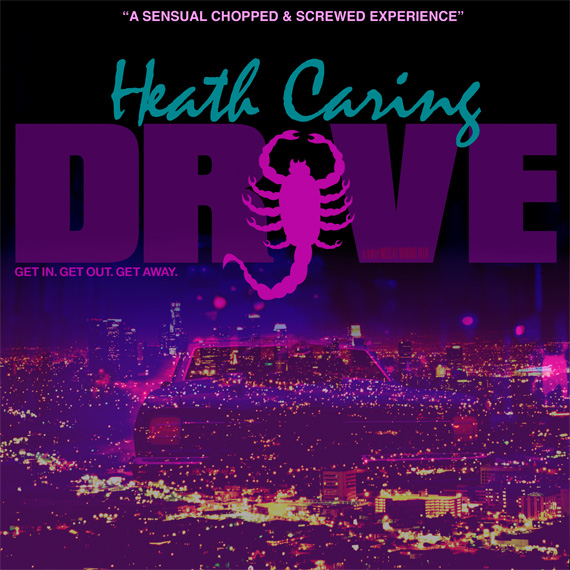

Drive by Xheathcaresx

Press play on this joint while you read.

I’ve been thinking about writing about chopped and screwed music for a while now. This cat named Heath Caring created a C&S version of the Drive soundtrack and it came on my radar a little bit ago. I’ve been regularly spinning it ever since. The problem is that the appeal of screw music is such a weird and specific thing. Screw music is post-modernism stacked on the already pomo origins of rap. I’ve been mulling it over for days, trying to find an angle of attack, but it’s a slippery subject.

My man Ray, a dude who has put me onto a lot of good screw, recently said this while spotlighting a new screw mix:

I’ve come to realize, trying to explain chopped and screwed music to people makes you sound like you’re fucking insane. The idea of slowing down music and making it skip on purpose isn’t the easiest thing for heads to imagine. That’s why instead of explaining what the music actually sounds like it’s best to describe the feeling screw gives you. Sometimes you feel like you’re being dragged through a black hole where time and space are being warped. Other times screw feels like you’re at a dope pool party but you spent the entire affair chillin’ out at the bottom of the pool listening to the DJ do work.

And that’s it right there. It’s about the music, but it’s not. It’s about how it feels. Listening to screw, whether you’re sober or high, is like listening to regular music, sure. There’s a beat, and you can bop to it. You might could even do a slowed down version of the wop to it if you had the right song, and I mean the wop that your parents used to do when they hit up house parties, not the wack dance that swept youtube a few years back. But screw music is… it’s like abstracted rap. Not abstract, like Q-Tip or Aes Rock. Abstracted. Taking a thing and making it different. It’s psychedelia for people who were raised on Three 6 Mafia and UGK instead of The Beatles.

But it’s real hard to explain what screw music sounds like to people who can’t parse the idea that DJ Mr. Rogers’s chopped and screwed version of Drake’s “Say What’s Real” sounds like the feeling you get when you walk into a black mass in the basement of the club by accident and realize that the chief anti-priest is your ex-girlfriend. The way the harmonious melody in the background is slowed down changes its sound from a generic triumphant rap orchestra into a funeral dirge, Drake’s voice goes lower and he’s enunciating clearly, but the track keeps skipping and hopping and stripping all the smooth charm out his voice. That feels different from “I like how John Lennon sings this song because you can hear the hurt in his heart” to me.

I’ve been describing that screwed version of the Drive soundtrack to other people as evil, like a house party in Hell in the ’80s where all the coke’s run out. Kavinsky’s “Nightcall” turns into something else entirely when the upbeat synth-pop gives way to a voice that moans and groans the words out and the synths are stretched to the breaking point. It sounds slow, is the thing. It sounds wrong, and I mean wrong in the sense of what it feels like to come into your house and realize something is out of place, but not being able to figure out what that out of place thing is or who could have been in there but you. “Nightcall” turns into the musical equivalent of a gross leer, and you can’t do anything but let it wash over you.

The wildest part of the mix to me is the point when Kendrick Lamar’s “ADHD” rolls in. I didn’t even realize that it had faded in on my first listen, because it’s slipped in there so smoothly and the song sounds so different. There’s a great thematic link between Drive and Lamar’s Section.80

, but the screwed “ADHD” tripped me out. It fits so well, and the Clipse joint that comes after is tremendous.

It sounds so full, like it’s just overflowing out of your speakers. It sounds like something you want to bang so loud on your speakers that your neighbors spontaneously shatter into dust from the bass. Like a… like a sustained earthquake, or something. It rolls over you and makes you feel trapped. Claustrophobic. The lyrics twist and turn uglier than they might be at first glance when they’re this slow.

This specific example of screw music is like the most comfortable uncomfortable situation ever, like the tail end of what happens when you screw up and eat an entire hash brownie, not realizing you only needed half to get right. It feels like that last hour or so of being over-high for thirteen hours straight, when you’re done panicking and you know you’re way too high, but man the couch feels too good right now and you feel so relaxed and life is so nice that it’s all to the good.

I like this Lil Sprite mix Ray hooked up, too. It’s called Cocaine Pentagrams, which makes it incredible from jump. Sean Witzke was on Twitter talking about how it made him think of David Bowie’s Station to Station, and I hadn’t made that connection, but it’s dead on. Station to Station is an incredibly funky album, and one of my favorite Bowie joints. He was so coked out while working on it that he doesn’t even remember doing it.

At the forefront of my mind was Andre 3000 beginning a verse “I came into this world high as a bird from second-hand cocaine powder” and ending another “They call it horny because it’s devilish, now see, we dead wrong.” on ATLiens. Bowie is just the icing (provided by Freeway Ricky Ross and the CIA) on the cake, the missing puzzle piece that pulls it all together. Just from the start, Cocaine Pentagrams is ill, and that’s without even hearing a single word. It’s evocative. It’s the precursor to an experience.

It’s not just about slowing down a song or getting high and turning on an mp3. It’s an experience that’s different from how I regularly listen to music. I try to really listen when I’m playing songs, but with screw music, I just go with it and see what happens. I do a lot of writing to screw music. It just sorta sits at the back of your head, infecting your subconscious until you’re through. It’s music that’s easy to absorb when you aren’t thinking too hard about it.