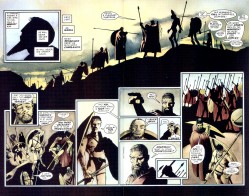

3 Formative Works: 300

August 6th, 2010 Posted by david brothers

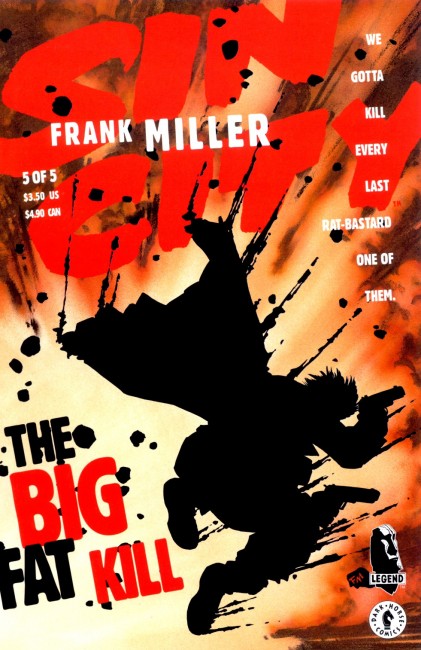

Frank Miller and Lynn Varley’s 300 was probably the first comic that I really dug into and absorbed. I’d read and reread several comics before, most notably a couple of Akira softcovers I’d inherited (remember those? I ended up trading for a few) and the last chapter of Sin City: The Big Fat Kill, but I’d never really dug into them. Comics blogging didn’t exist when I was a kid, all we did was talk about how cool it was that people had guns and argue over how many copies of Brigade 1 X-Men 25 was worth.

But 300–I picked it up because I recognized Miller’s name, and didn’t care that it was in Spanish because the art was dope. Poring over it and rereading it actually helped me learn Spanish, and I ended up quizzing my teacher over words I didn’t know. “Hace apenas un año,” a caption early in the book, threw me off at first, for example, but once I got it, other words and phrases began to fall into place.

I read and reread 300. I absorbed it, and that’s corny, but really the only way to put it. If you’ve ever fallen into a book like I fell into 300, you’ll understand.

What’s weird is that I’ve been writing about comics for the past five years, slowly getting better at critical analysis, and I’ve only ever written about 300 once, and that was as part of a review of the (in hindsight) crappy movie. Everything else, every other time I’ve mentioned it, has just been in passing, or relating the story above. I haven’t been avoiding it, but I haven’t exactly felt led to write about it, either.

It’s not that there’s nothing to write about. The last time Miller made a comic that wasn’t worth examining in detail was probably his early work on Daredevil. There’s always something to look at and pull apart, whether that thing is how Miller’s changed approach to superheroes intersected with 9/11 and brought Batman kicking and screaming into realpolitik or how 21st Century Frank Miller’s biggest enemy is 20th Century Frank Miller.

(Digression: Miller’s rep in the blogosphere has been boiled down to “WHORESWHORESWHORES” due to the fact that people can’t separate jokes from actual criticism/examination. The image of Miller as a leering, super-serious sexist monster only tracks if you’re ignorant of his body of work–the Martha Washington books, Hard Boiled, Ronin, etc. He’s got a wider range and better sense of humor than most people seem to give him credit for, though he can be awfully self-indulgent at the same time. What I’m saying, I guess, is step your game up, internet. This is basic stuff.)

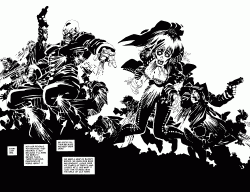

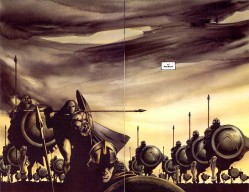

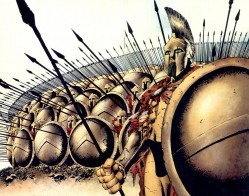

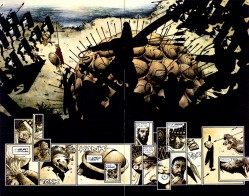

I think part of it is that 300 is just a very straightforward book. I’m not saying it has no depth, but it isn’t tough to suss out what Miller’s playing with in the story. If you pull 300 apart, what you’re left with is Miller’s entire career. It’s not an end point, obviously, but it is something that he had to make at some point. Just look at the chapter titles: Honor, Duty, Glory, Combat, and Victory.

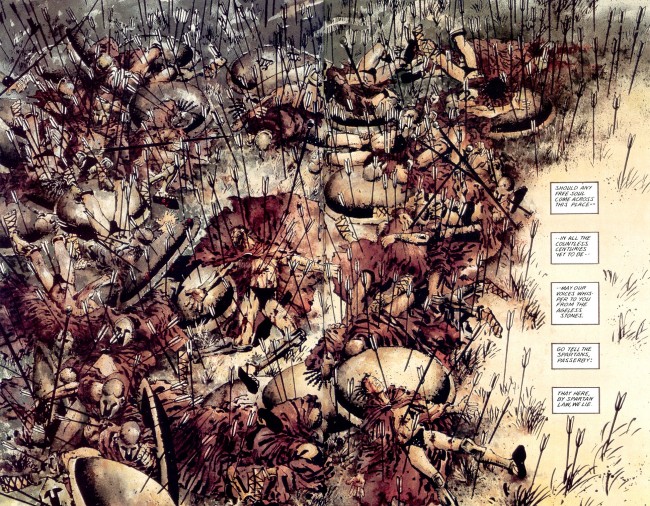

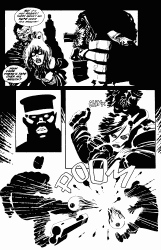

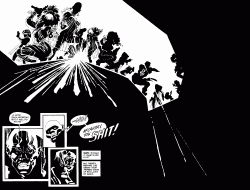

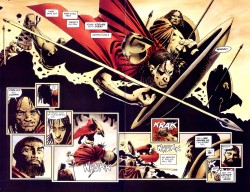

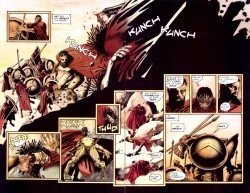

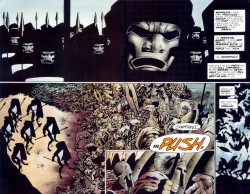

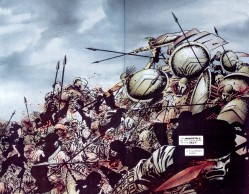

300 is everything. There’s the hard Dirty Harry morality, the strength tempered with love, quiet and graceful violence, ugly violence, brotherhood, casual male and female nudity, the rejection of cowardice, some obscenely good one-liners, self-sacrifice, corrupt politicians and priests, and hey, look, what’s that at the end of chapter 4?

Ninjas.

Miller has said that he started Sin City because he wanted to draw manly men, sexy women, and old cars. Daredevil and Ronin had ninjas and samurai because Miller was into manga and martial arts flicks. Miller did covers for the First Comics editions of Lone Wolf & Cub, a series all about duty and honor and the proper application of violence. 300 has its roots in an old movie he saw as a kid. Frank Miller draws what he’s interested in at the time, and you can track those interests in his work. There’s even a 300 tease in the last chapter of The Big Fat Kill. This is clearly a story he’s been interested in forever.

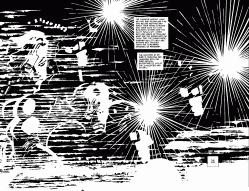

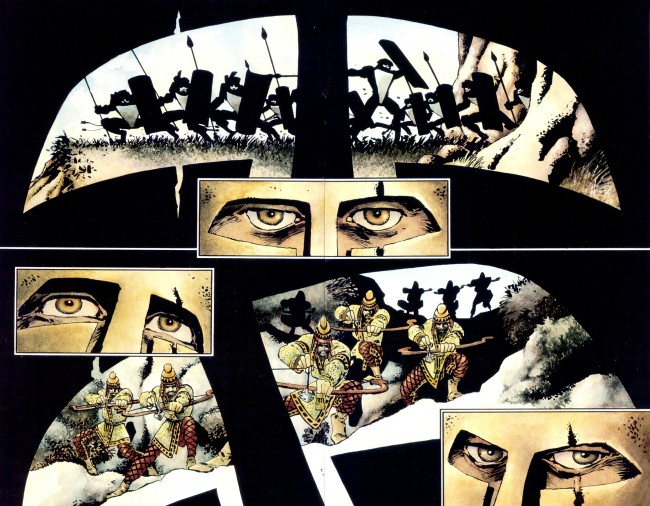

While I don’t think I ever really consciously realized this while reading and rereading, 300 is where close reading began for me. I studied it closer than you usually study comics, due entirely to the fact that it was in another language. It’s not my favorite of his books, though I do like it a whole lot, but it’s kind of interesting to look back at it and everything I learned from it without being conscious of that education. I started picking up on his magic tricks (the last chapter goes first person as Leonidas surveys his enemies for a few pages, and then pulls out to show the full Spartan might) and tics (repetition of dialogue and captions for emphasis and pacing) and interests via, what, osmosis? By accident?

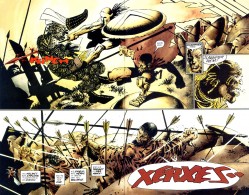

My relationship with 300 is weird. It never quite feels right to read it in English, the movie was several orders of magnitude less subtle than the book (“This is Sparta” was a sentence, not a scream), and the tone is strangely subdued in certain scenes. I think that, craft-wise, this is Miller’s strongest and tightest work, with very little fat worth trimming. It lacks the manic intensity of his more recent Batman work, but it also feels more grown-up. And the ending is dope–Leonidas simply saying “Stelios,” the leap that’s something of a callback to Stelios’s nickname “Stumblios,” all of it.

I’m glad I read it where and when I did.