The Prophet Exception: More On Artist Changes

February 26th, 2012 Posted by david brothersI said that artist changes due to double-shipping mainstream comics devalues the artist. Not all art changes are evil, though. Sure, some of them are of the Final Crisis variety and result in terrible comics, but every once and a while, people get them right. Artist changes, guest artists, however you want to call them–they can be used tactically, as a way to showcase an artist or add a little extra punch to a storyline.

This may be weird, but follow along for a minute. One of the best examples of the way a guest artist can make something extra dope is a song. It relates to my point about unwanted art changes being like new actors showing up in old roles in a movie or a song changing direction mid-stream. It’s Big Boi’s “Fo Yo Sorrows,” off that Sir Lucious album:

It happens around 0:55. Too $hort, the legendary rapper out of Oakland, pops up to drop four bars and then bounce. That’s a quarter of a verse. It’s a cameo, but it goes deeper than that. At 0:47, Big Boi flips the word “bitch” just like $hort made famous, and then says that $hort was one of his favorite rappers. For Too $hort to pop up on this song for something that’s little more than a cameo is ill. It’s rappers playing around and having some fun. It’s not really a guest spot. It’s something you smile about, because you’re in on the joke.

That’s the feeling that art changes should give you. A little spike of glee, or a chance to explain to everyone you know exactly why what just happened is so good.

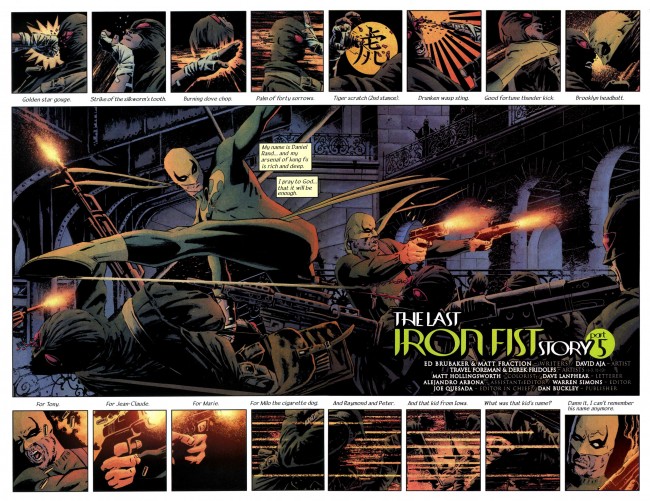

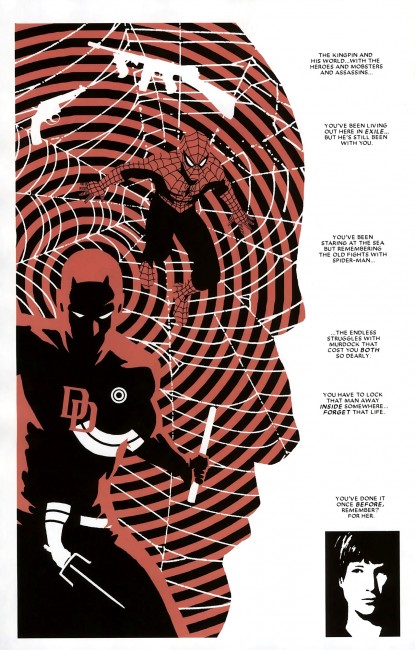

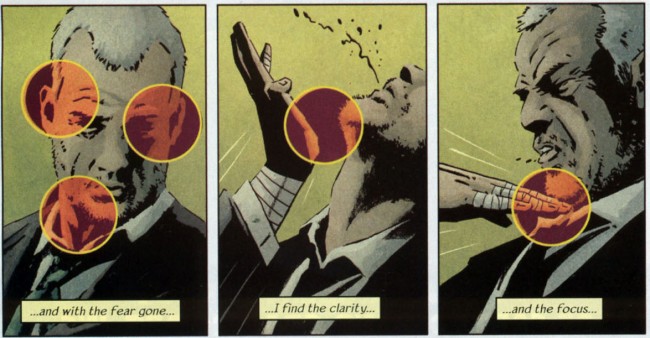

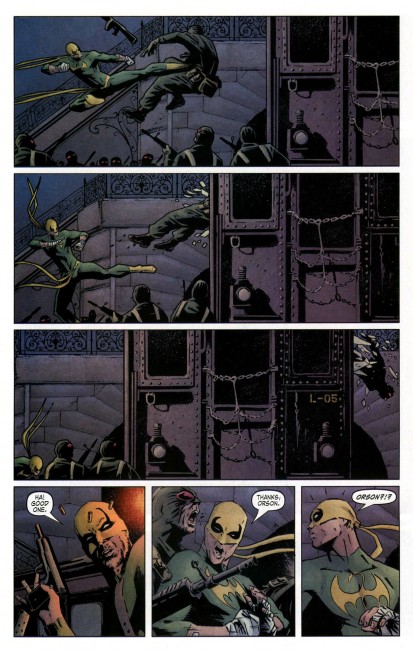

The Immortal Iron Fist did it well, for the most part. The flashbacks to adventures of other Iron Fists were drawn by a variety of dope artists, each one tackling a different Iron Fist. David Aja drew the modern pages, and his art served as connective tissue between the flashbacks. He set the tone and stage for the book, and then when the story required that the tone and stage change, Travel Foreman, John Severin, Russ Heath, and Sal Buscema tagged in to get it done. Aja is Big Boi, and John Severin is Too $hort. He brings with him a history and pedigree that people on the inside will get, while others will just go, “Yo, that looked pretty cool.”

Big Boi/Matt Fraction/Ed Brubaker had a good reason for their guests showing up, too. It’s not just a willy-nilly thing. There’s a point. It’s an enhancement, rather than someone just plugging another gear into the mix so that the machine goes faster. It turned Immortal Iron Fist into a jam comic. It provided variety.

There’s a really good example of what I’m talking about coming up later this year. Prophet started life as a Rob Liefeld/Dan Panosian joint. As part of the big Extreme relaunch, it’s currently in the hands of Brandon Graham, Simon Roy, Richard Ballermann, and Ed Brisson. It’s really good, actually, part of the continuously rising wave over at Image. Graham is writing, but working closely with Roy to make the story the best it can be. Sometimes that means layouts, other times it means Roy making sure that Graham’s on point or vice versa. It’s a collaboration. And there’s going to be guests popping in. From Graham’s blog:

So I’d written on here before that Prophet would come out 6 times a year but some cool shit has happened and now it’s going to be 12 issues a year monthly.

So here’s the schedule:

Starting Jan-

#21(number 1 in our hearts) -#23 art by Simon Roy (Jan’s Atomic heart), then #24 &25 are drawn by farel dalrymple (pop gun war) I’m drawing #26 and Giannis Milonogiannis (Old city blues)is doing # 27- 32. I think we’ve come up with a cool way to make this work storywize.

The situation isn’t too dissimilar from Marvel, and I’m sure a lot of people will say it isn’t different at all. There’s a comic, and the people making it want it to come out more frequently, so more artists are joining the team. The original draw of the series was the Graham/Roy/Ballermann/Brisson team, and that’s changing. I think that there’s a difference here, but a very, very fine one. I don’t think the difference is “I like these guys,” either. I like a lot of them dudes who are coming onto books I like, too.

Instead of just slipping new dudes into the rotation to boost the schedule, editor Eric Stephenson and writer Graham have found artists to work with and crafted the story around them. My understanding is that each artist will be working on a story tailored for them, rather than simply being used to keep the ship on track. All of the artists are doing covers, too, I suppose as a type of introduction. There’s a creative reason here, and I think that has more value than the purely economical reasons Marvel has to have artists playing musical chairs.

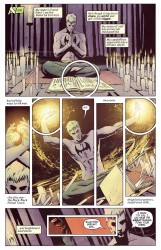

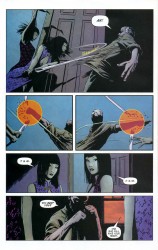

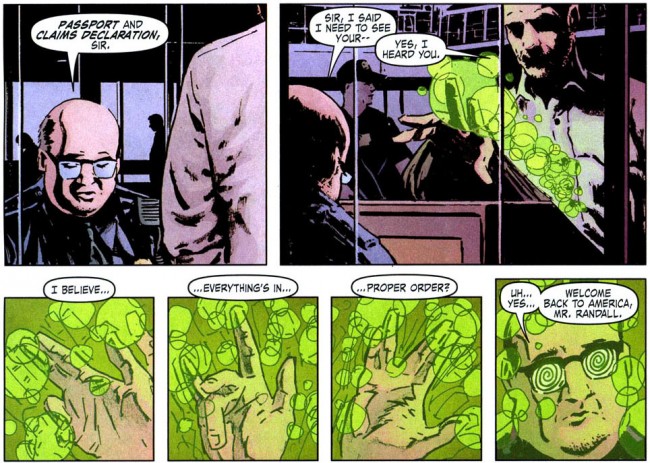

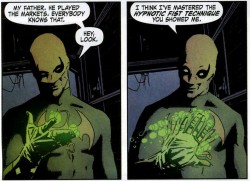

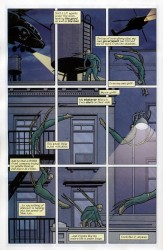

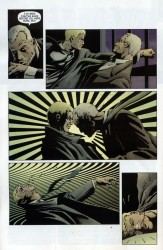

Here’s the covers for Prophet 22-24 and 26. The covers are by Simon Roy, Farel Dalrymple, Giannis Milonogiannis, and Brandon Graham, in that order.

They have absolutely distinct styles, right? Roy & Ballermann’s palette is dusty and soft, Dalrymple’s muted and night time-y, Milonogiannis’s is aged, and Graham’s is soft, but in a different way than Ballermann’s. Firmer, maybe. Roy & Ballermann’s art is rough and loose. Dalrymple is detailed and gloomy. Milonogiannis is… I don’t even know the right word for it right now. Majestic? Ominous? I get the feeling of mankind making contact with an entirely alien and apathetic intelligence, something that sees us as being beneath its notice. And Graham’s cover for 26 reminds me of nothing so much as the passage of a lot of time.

Things like this make art changes into events. It’s not just “Oh, we want to make people buy this book sixteen times a year instead of twelve.” It’s “We want this book to be the best it can be.”

I think it’ll work. I’m looking forward to finding out.