I’ve been wanting to write about Marvel’s ’70s comics for a while, especially the ones featuring Luke Cage and the Black Panther. I do it here and there, but never in depth, because I haven’t found a subject that I really want to put my foot in yet. Just a nebulous “Oh I should do this sometimes.”

I started work on a piece springboarding off an excerpt from Grant Morrison’s Supergods that was a good example of what I don’t like to read when people are talking about ’70s comics. Part of chapter 11 is dedicated to what Morrison terms “the relevance bandwagon,” the stream of socially aware or conscious comic books that began coming out in the early ’70s that included books like Green Lantern/Green Arrow and Jungle Action. It’s also the only part of the book where Morrison spends any amount of time discussing black comics characters in detail.

Morrison got it wrong when it came to why those books were relevant and good comics, basically, in a couple of different ways (factually, thematically). He got it wrong in the same way that people keep getting it wrong when they talk about this stuff. He spends more time on that stupid Lois Lane comic where she turns black for a day than John Stewart and Luke Cage combined, right? Which makes the entire affair feel condescending bordering on dumb insulting, especially when he says that Luke Cage “soon outgrew his origins to develop as a rich and enduring character, still central to the ongoing Marvel story decades past Shaft and Jim Kelly.”

Yeah nigga naw, Luke Cage has been rich and enduring ever since page one, panel one. The redemption story sucks because it erases the history of the character and the people who created him. I’m really fond of the Kurt Busiek and Jo Duffy eras, less so the Steve Englehart-scripted issues, but there’s a ton of things in there to enjoy. Not to mention the art teams, you know?

Hiding that history behind the idea that Cage needed rehabilitation hurts comics history. You don’t get Milestone Media without black artists finally getting a chance at the big leagues in the ’70s. Denys Cowan studied at the feet of Arvell Jones and Ron Wilson, among others like Rich Buckler and Neal Adams. Years later, Cowan bugged his friends with the idea that they needed to set out on their own and take full control of their careers. Then: Milestone, a company that focused on representing the world at large, across a wide variety of cultures and orientations and philosophies.

As halting and awkward as Luke Cage occasionally was, it’s not worth losing that history to point out how far we’ve come. I guess it’s a big deal to me because we’ve already come pretty far, and it was ten years before the theoretical redemption of Luke Cage. The redemption story furthers the idea that the mainstream comics industry was adrift when it comes to this stuff until NuMarvel, and that’s just silly. We’ve been better, and then we lost it, and now we’re trying to get back.

But I can’t make this post of mine click like I want to, no matter how clear I am about the component parts of it. I want the Supergods excerpt to be a springboard, not the focus of the piece. “This book doesn’t have it right, and here’s a corrective that can stand on its own.” vs “This guy is a big dumb face who didn’t pay enough attention to this thing I like in his big ol’ dumb face book.” I do care that Morrison got it wrong — it definitely put me off the book, even after a friend was kind enough to get me a signed copy from the UK because I am the BEST FRIEND — but I’m not interested in debating how or why he got it wrong.

That kind of point-by-point rebuttal isn’t where I’m at; it isn’t what I like to do. It makes my text too dependent on his, rather than something that can stand on its own two. I just want to talk about how these colored folks from times past laid the foundation for Milestone or how Luke Cage goes way deeper than “where’s my money, honey?” pretty much from the start of his series. I want to talk about how it wasn’t the social relevance that made these comics so enjoyable and important. The social aspect was important, sure, but that doesn’t mean anything if the books aren’t good. No, when I look at those books, I see a sudden burst of inclusion, not just comics writers exploring politics. Those books gave normal people who were underrepresented in these wonderful universes sudden representation, and it oftentimes turned out pretty well. Marvel especially managed to capture a specifically black aspect of the zeitgeist very well, and married it to their continuity in a way that worked really well. When that got stale, they hitched kung fu to Luke Cage’s truck and pow, they were right back in the thick of it.

So my springboard ended up being a stumbling block. There is no post that’s pure enough, not yet. But I’m used to this. I can’t fold, so I re-up and reload. I’m okay with having ideas that don’t make it from conception to birth. Ideas are cheap. There’s a kernel in my scrapped draft (technically 1.5 scrapped drafts) that I’ll be able to plant elsewhere and let it grow to fruition at some point. Plus, it’s nice to have crystallized those ideas over the course of writing the failed post, but that post ain’t what I need it to be. It’s not what I want, no matter how many words or secret rap lyrics I add to it. One day I’m going to find that trigger and squeeze it and blow someone’s mind, but today wasn’t the day. If you read my tumblr, you’ve probably seen a lot of ideas that didn’t quite go anywhere until months later. Build and destroy, right?

Writing about race is so weird. I often feel like I’m walking on eggshells or tip-toeing across broken glass sometimes, despite how often I’ve done it and how comfortable I feel with doing it. Like, as soon as you acknowledge that race exists and affects things in a positive or negative or in-between manner, armies of dudes strap on their fedoras and get to typing about how it’s not that serious, you’re reading too deep, why you gotta play the race card, chill out, bud, can I call you bud, my black friend lets me call him bud when we hang out, I’m down, brother. Or whatever. This paragraph got weird.

I wrote a thing about Robert E Howard’s racism a few days ago and didn’t say anything about the subtext beyond what like a moderately culturally-aware teenaged black kid would notice, like how power is clearly distributed across skin color lines or how the sexual aspects of a certain story break down and relate to its racial aspects. I talked about things that have been around and part of American culture for centuries, even if they’ve only relatively recently been named and shamed. Basic racial awareness stuff, right, like avoiding “niggardly” because it’s awkward and you’re probably a jerk if you’re intentionally using it around black people or not touching or asking to touch black people’s hair.

Darryl Ayo said “I love when David Brothers explains very carefully and in detail about racist undertones in a work and some commenter is “uh uh, no!!”” on Twitter and I was like pshaw, I got this son, watch me do the knowledge and stunt on these bros… and then some dude told me to keep my emotions and politics out of things I read even if they are by an actual racist because I didn’t do the research and it doesn’t mean anything if he didn’t mean it and I had to slam the comments shut before I lost my doggone mind.

I think that’s part of why I try to keep the tone light when talking about race and comics, because it’s clear to me that it makes a whole lot of people (some people can’t separate what they like from who they are) uncomfortable, even if it’s something innocuous as “this racist guy wrote some racist stuff by accident.” I even brought a couple of gifs out of retirement, even though I don’t really get down like that any more. Keeping the tone light is a defense mechanism, I think, because it lays a foundation for me to laugh it off when things get stupid, as they do 99% of the time. If I poured my heart into something and kept it clean and then some schmuck came along talking about bootstraps, I’d feel much, much worse than when someone takes a lazy jab at a post with a funny gif of Method Man and Redman in it.

But I don’t think trying to lighten the tone actually works like I think it does? It makes me feel like I’m tip-toeing around what I want to say. Which, in turn, makes me think that maybe I should just go in and make things even more plain, because if people are going to flip regardless, why should I stress over how something is going to be taken? I could talk about things like how unbelievably off-putting it is that Brian Bendis and Sara Pichelli’s otherwise divine Ultimate Spider-Man features a black dude named Jefferson Davis, especially considering that the book was sold on the back of its lead being black and latino.

How do you talk about that bout of tone deafness — which should probably be explored at least a little bit within the greater context of well-intentioned tone deafness in the comics community, which I would argue is probably the biggest race-related problem in mainstream comics — without being an unfair dick to Bendis, who apparently named the character after a friend and not the dude who was a scumbag traitor to the Union who took up arms for his right to be a racist and own other people, like that’s a cool thing for people to do? (I went to a school named after Jefferson Davis for a while and basically wanted to die.)

I don’t make a conscious try at it, but I feel like I’m real layman friendly. I don’t talk about privilege or whatever other big words people are using to talk about race and culture. Not because I don’t like them or don’t understand them, but because that’s just not how I think about race. I didn’t go to college for this stuff. I’m either speaking from my own life experiences or those of people I’ve read, known, or respected. Some of it’s book-learning and some of it’s personal trauma, but you know what I’ve found is the most true and most effective when talking about race? Common sense. Racism, as a philosophy and practice, does not make common sense. It makes economic and nationalist sense, but not common sense. So, I’m just trying to say what I have to say in a way that everyone who pays attention can overstand it. It’s complicated, but it’s not complicated. You don’t have to talk about it like it’s astrophysics or microbiology or uh… precalculus. It’s best understood and discussed in basic terms. It’s thorny, I think is the word I’m trying to pull off the tip of my tongue, and complex, but not incomprehensible. “Food for thought, you do the dishes,” like an aight man once said.

I have a voice and a platform that a lot of other writers who care about black issues in comics don’t. I don’t have the responsibility to write about that stuff, because I firmly believe in doing what I want, when I want, and how I want to do it, but I do have the inclination to do so. I enjoy it, at least at first. It’s like therapy on a budget, and a few people have written in to say I helped them figure things out in their own life, which is awesome/terrifying/awesome.

I really, really care about this stuff. I care about others getting it right and I definitely care about getting it right myself. Otherwise, you get “LOL Luke Cage” instead of treating the guy like his history is as rich as it actually is. Which I think is why I’m so careful and pointed about what I don’t. I’m playing with the cultural equivalent of a loaded gun here and throwing in a bunch of rap lyrics and jokes. But I don’t want people to misconstrue what I’m saying or get it twisted, so I pick my words very carefully. Deliberately. Some people are still going to get hot under the collar, but “fuck boys do fuck shit,” right? I just have to do what I do and keep focusing on getting better at it instead of the dudes who are mad that their favorite comic is pretty crappy when viewed through a certain light.

I think about this stuff a lot. I mean, the REH post I wrote on a Saturday morning because I was bored and felt like it, but the ideas in there definitely percolated for months before I put them to paper. At the very least since I read the first issue of the Conan relaunch. There were six or seven issues out when I wrote a post that mentioned REH’s racism in passing, so let’s call it six months. I notice something, I talk with friends about it, and then I push it to the back of my mind, where the real work gets done, until I have something to say.

Even when I’m shooting from the hip — usually on Twitter, rarely on 4l! — it’s never just to talk or something I’ve only half-examined. I think about the intersection of race and comics so much because I feel like it’s something that is incredibly important that is vastly underserved, or outright mocked, on a mainstream level.

Like, here’s a real life example: I mentioned the gross aspects of interracial (again, genre, not description) porn in that REH post, and the way it plays upon the fear of a white woman being tainted by the black penis. Some of it focuses on the shame of a white guy that a white woman would sink so low, which is the really, really gross stuff, but most of it’s about debasement. “She said her price’ll go down if she ever fucks a black guy, or do anal, or a gangbang; it’s kinda crazy it’s all considered the same thing.” if you need a topical reference and/or a reminder that Kanye’s “Hell of a Life” is a shockingly good song.

Luke Cage and Jessica Jones’s relationship began with rough sex in Alias #1, a Bendis/Gaydos joint. (I swear I’m not trying to pick on Bendis here, I’m just going with whatever examples come to mind and I’ve read a lot of Bendis comics. Probably more comics by him than any other singular author outside of Garth Ennis or Grant Morrison, honestly.) It was intended to show her at her lowest, how actively self-destructive she was being at that time in her life, back before she got married and had a kid with Cage. How do the fans refer to their hookup in that first issue?

“Interracial anal.”

Alias is a good comic. I went from Daredevil directly to Alias and had a grand old time. But how am I supposed to feel about that aspect of the series? It’s 2012, the issue came out in 2001 or whatever, so these jokes aren’t new. And that’s the go-to joke? That’s how people describe that scene? If I tell somebody to read that comic, five’ll get you ten that some schmuck is going to pop up with a dirty joke about it if that person decides to talk about it online. And that’s pathetic.

There’s already something uncomfortable about the debaser being black and the debased being white, regardless of Bendis’s motivations when writing. Bendis stuck the landing on that front in the text, but outside of it? He’s enabled his fans to run with this, make cute image macros out of it, and I’m like 90% sure he’s brought that phrase up in the Powers letter columns himself, though in a self-deprecating way.

I’m not with that. Not at all. I said a while back that one of the biggest parts of being black in America is being constantly reminded that you are black. That’s a clear example. Black is different, black is weird, black must be pointed out when you see it, especially when it contrasts with normal. I mean, white. It makes you feel like you don’t belong every minute of every day, like you’re an intruder in the only home you’ve ever known.

And I’m not even talking about this like I think Bendis and his fans deserved to be nailed to the wall for whatever. That’s not where I’m at, and it’s not how I work. But I do think that not talking about it, not having that conversation, knowing how crappy it makes me and people I know feel, is a mistake. Having that conversation is at least as important as talking about when somebody gets something so right that you’re left amazed. Talking about race can’t be limited to just dudes in white robes burning crosses or racial profiling. We have to talk about the little things and the everyday things, too. “Don’t go to jail unless you want to be Antwan’s wife!” things, or “That’s so ghetto” things. “Storm and Panther only got married because they’re black!” things.

Race is bigger than racism. Racism, as far as I’m concerned, is a small and probably the least interesting part of talking about race.

Why do I write about race? Partly because other people are so terrible or inept at recognizing the impact of race on their life, let alone actually talking about it. When I first started, it was a lark. Then I thought I could convince Marvel and DC to do something other than pander to their audience. Then I realized that was stupid, and I’d be better off just talking about this stuff. I’ll spit hollowpoints at them them when they miss, praise them when they hit, and hopefully someone who reads me will look and go, “Oh, this makes sense” and tomorrow will be a little better.

It took me forever to come to that point, though. I figure it’s obvious if you read my posts from that first Black History salvo on through today. Maybe not. Maybe I’m the only one that pays that much attention to what I do. But I have changed and grown as a result of talking about race and comics.

I can’t really speak authoritatively on the Big Two’s racial issues any more, outside of when they step into a realm where I don’t need deep knowledge of their books, and I’ve more than dipped my toe into spotlighting black creators of all stripes. I just need to figure out where my lane is now, where I best fit in, and how I can continue the conversation.

I want to continue the conversation because it’s too important to leave alone, no matter how much I get down on it sometimes. It’s too important to me to leave alone. I had to piecemeal together black heroes and history as a kid. If I can save someone the trouble, so much the better. I want to continue the conversation because if I won’t, that cuts the number of vocal black people willing to get their hands dirty about race & comics and have a platform like I do by half. It’s me and Hannibal Tabu out here, unless someone’s slipped my mind. (There are no black women at the big sites, which sucks. But I know of one site that’s actively working on it.)

I feel like I needed to say this here so that I don’t need to say it any more. I’m working this out in public. Thanks for following along.

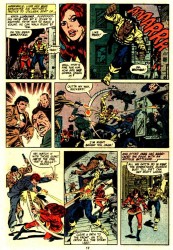

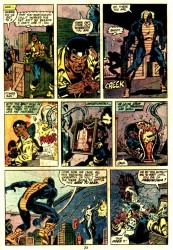

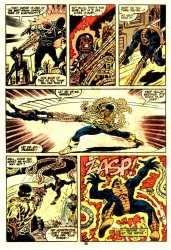

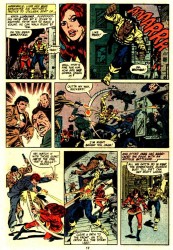

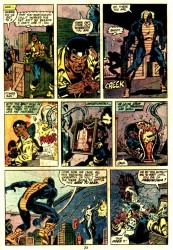

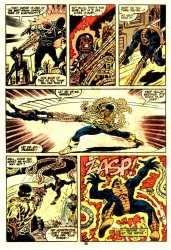

(Luke Cage, forever thugging. The images in this post are two of my most favorite Cage comics. The old, dirty scans are from Essential Power Man and Iron Fist, Vol. 1 (Marvel Essentials) , with words by Mary Jo Duffy and pictures by Kerry Gammill and Ricardo Villamonte. The newer scans are from New Avengers: Civil War

, with words by Mary Jo Duffy and pictures by Kerry Gammill and Ricardo Villamonte. The newer scans are from New Avengers: Civil War , with words by Brian Michael Bendis and art by Leinil Yu. I love that Cage, as a character, is strong enough to support stories of both types, and can be funny without being a buffoon. Luke Cage was created by John Romita, Sr and Archie Goodwin. Thank you.)

, with words by Brian Michael Bendis and art by Leinil Yu. I love that Cage, as a character, is strong enough to support stories of both types, and can be funny without being a buffoon. Luke Cage was created by John Romita, Sr and Archie Goodwin. Thank you.)