When someone dies in cape comics, the first reaction tends to be some flavor of, “Oh, they’ll be back. No one stays dead in comics.” Which, okay, that’s fair. Marvel and DC have cultivated a revolving door sort of status quo for whatever reason, and you’re more likely to see someone back than not if they were ever worth anything.

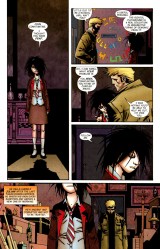

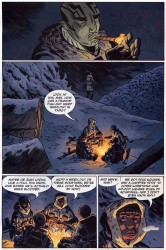

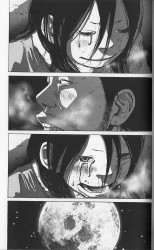

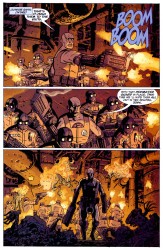

BPRD , though. Maybe it’s due to being a product of Mike Mignola’s Hellboy, maybe Mignola, John Arcudi, and Guy Davis are more willing to break the toys they’re playing with, but when someone dies in BPRD, whether a main cast member or a random cannon fodder schmuck, it counts. There’s no hand-waving, no cheap tricks to squeeze a few more dollars out of some IP, none of that. There’s just a villain saying “He won’t,” and then someone you’ve grown to love, another in a long line of lost souls, is gone forever.

, though. Maybe it’s due to being a product of Mike Mignola’s Hellboy, maybe Mignola, John Arcudi, and Guy Davis are more willing to break the toys they’re playing with, but when someone dies in BPRD, whether a main cast member or a random cannon fodder schmuck, it counts. There’s no hand-waving, no cheap tricks to squeeze a few more dollars out of some IP, none of that. There’s just a villain saying “He won’t,” and then someone you’ve grown to love, another in a long line of lost souls, is gone forever.

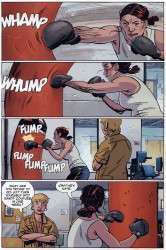

Having genuine stakes is part of what makes BPRD so entertaining. Batman will never die, Superman will never die, and Spider-Man will never die. Liz and Abe and Johann can and will bite it, or be moved so far out of their comfort zone that we become uncomfortable and unsure. You don’t know what can happen, because people can and will be taken off the board as needed.

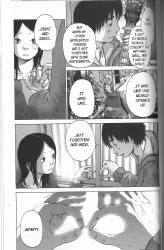

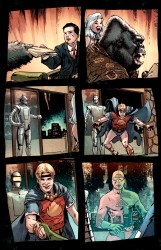

BPRD is theoretically Hellboy‘s little sister, but has a very different approach to storytelling. Hellboy always struck me as being as much about the creatures that Hellboy gets into it with, and the mythologies he walks through, as about Hellboy himself. BPRD is about Kate, Liz, Abe, Roger, Johann, and the way that the pressures of their job, which is leading headlong towards some kind of apocalypse, bends them in funny ways.

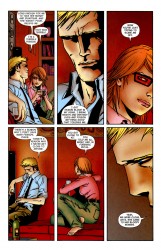

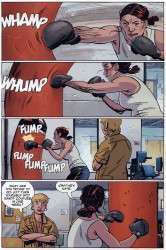

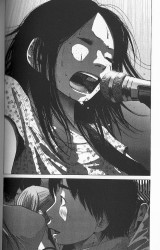

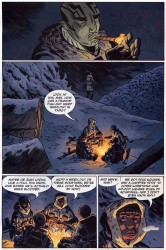

The cast is really what makes BPRD work. The plots are great, and Guy Davis’s art is fantastic, but I think that the way the characters bounce off each other is my favorite part of the book. When the series kicks off, they’re stuck in a post-Hellboy rut. He left the team fairly recently, and he was in a very real way the sun to their solar system. Without him, they have no center, which means that certain people find their roles have shifted in strange ways after the change. It’s positively melancholy, like they’d just found a hole where there shouldn’t be one.

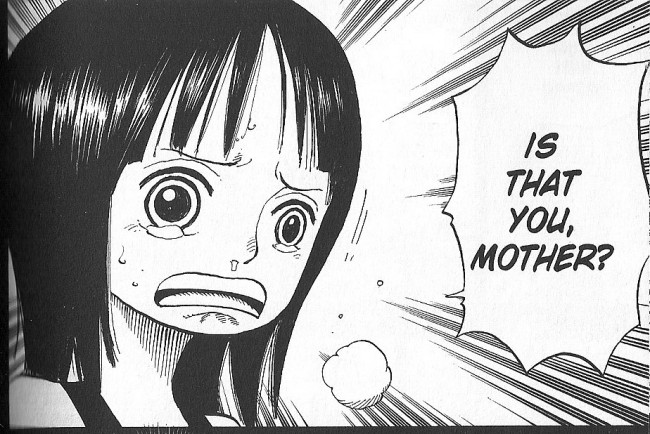

Over the course of ten or so volumes, you get used to these characters. You see Abe trying to fill Hellboy’s shoes and coming up short. You see Kate trying to keep the BPRD under control and on the ball. Roger is desperate for a friend and imprints on people. Liz is haunted by visions of a toxic future and finding herself increasingly divorced from her friends. The normal humans are overwhelmed and outclassed, but there to do their job.

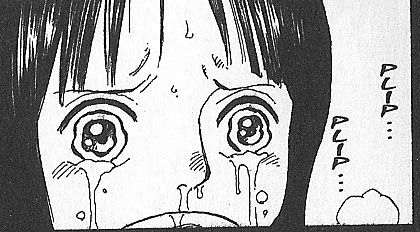

A lot of the characterization is left for you to figure out. No one explicitly says that Roger is emulating his role models, but it’s clear if you pay a little attention. When Liz goes all wan and sullen, the way Guy Davis shows her cutting her eyes and poking out her lip is crucial. Abe butting up against authority is another clue. No one stands up and says, “I am feeling sad.” The BPRD talk like people, which means that a lot goes unsaid, people say a lot of things they regret, and they don’t always tell the truth. The little bit of digging required to really get these characters makes you even more invested in them. You realize things and it hits you like a bolt out of the blue. “Of course, that’s why this happened and why he said this.”

The story these characters are pulled through peels back like an onion, and you’re right there along with the BPRD. It’s like Lost, if Lost was better written, had dope art, and wasn’t massively frustrating. Only one person has the answers, and he’s more interested in being cryptic or obtuse than actually answering any straight questions. When he does begin answering questions, it’s too late. Answers are pointless at that stage. The apocalypse is here, and no one gets to stop it.

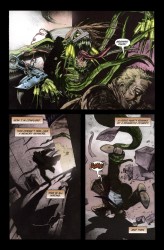

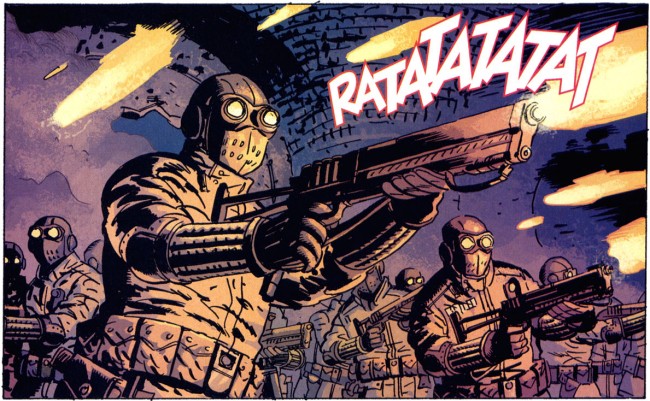

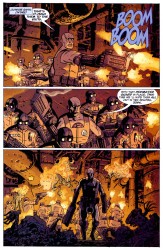

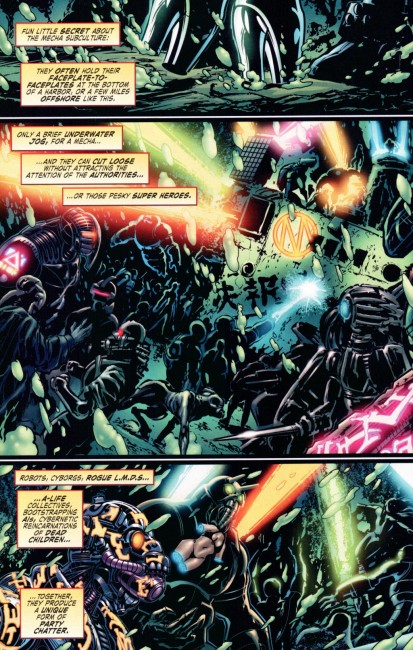

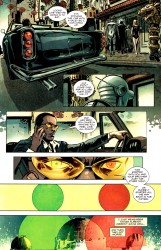

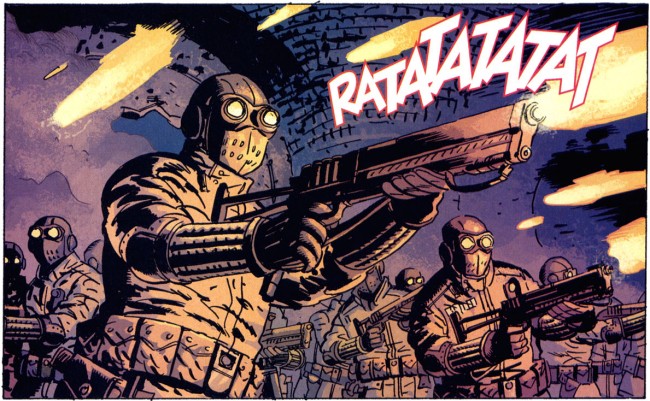

It begins with frogs. The frogs soon turn to monsters, and they run rampant over the countryside, quietly building an army. Another man, a corrupt businessman, decides to get his supervillain on, with unexpectedly catastrophic results. Something that once seemed like a minor infestation was discovered to be more rotten and vastly more widespread than expected. And through it all, the rock of the BPRD, Hellboy, was completely missing in action.

Imagine a snowball sitting at the top of a hill. A push in any direction and the snowball will roll down the hill, gathering mass on the way, until it becomes a problem. When we come in on BPRD, that snowball is already halfway down the hill. The problem is that the BPRD don’t have the perspective needed to see the full shape of the terror that’s coming, and missing that perspective leaves them ill-equipped. They’re playing catch-up, and while they do notch several wins, they aren’t fighting against something that you can just win against every once and a while.

The structure of the series, the sheer size of what Mignola and Davis and Arcudi are throwing at the BPRD, is only obvious once you’ve gotten hooked. BPRD is a juggernaut. Once you get it, once you see how it works, you can’t stop any more than the BPRD can stop what they’re fighting against. You start looking for angles, outs, and ways for the team to come out on top. The snowball is coming down the hill and your head is turning too slowly to actually see it in time. You start to put this together and that together and you realize that, no, things don’t look very good for our crew. But it’s an adventure comic, right? These things always work out well!

Except, BPRD is off in its own little world. It isn’t Superman or Spider-Man. When people die, they stay dead. And really, just when I was getting comfortable, a villain said two words that changed everything and reminded me of just what I was reading. This is the real deal.

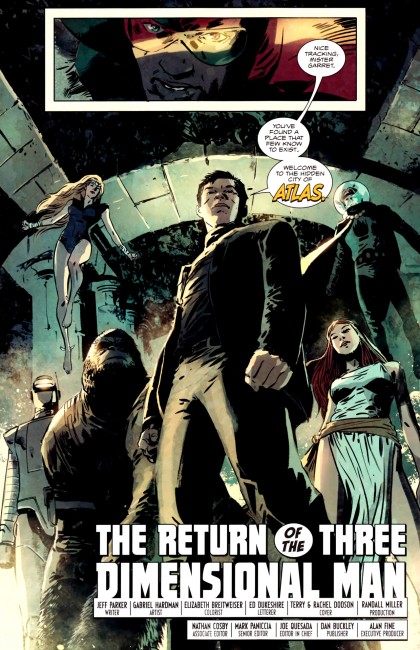

That’s something else that works in BPRD‘s favor. Nothing is created or consumed in a vacuum. BPRD is part of a 20-year old franchise that is in and of itself part of a larger tapestry of stories. You cannot separate BPRD from that tapestry, unless you’ve somehow managed to avoid serial superhero comics or adventure fiction entirely. Stories like BPRD, which you could honestly transform into a mainstream cape comic with a few minor changes, have certain expectations. Deaths don’t stick, enemies return, and if someone changes, they’ll be back to normal soon. BPRD bumps up against these expectations repeatedly and to great effect. You think that Liz or Kate or Abe or Roger will go back to how they were in book 1, but no, they won’t. The only thing they’re going to do is grow into whatever shape they need to fill in the next volume.

The key word for BPRD is freedom. Mignola, Arcudi, and Davis, among others, have the freedom to tell whatever kind of stories they want to tell, free of whatever expectations you may have coming in. The BPRD itself is free to act and live and learn and grow in ways that most major comics characters cannot, for better or for worse. Characters enter and exit the book as they need to and in a variety of ways. The cast isn’t static, and people you thought were lifers really aren’t. BPRD is free to push and outgrow its boundaries and become something completely unlike what it began life as.

The format of BPRD clicks, too. The series of miniseries is what I think all ongoing mainstream comics should adopt. Keep Amazing Spider-Man and whatever other series are creeping up on a thousand issues. That’s fine. Giving a character a series of miniseries, each able to stand on its own, but when taken together build up to a monster of a story… that’s the good stuff. BPRD is one of my favorite ongoing series, and the format is a large part of that. There is a clear reading order, clear stakes in every volume, and a slow upping of the ante that leaves you with something like chills by the time you get to the latter volumes.

Eleven volumes is a tough row to hoe, but not when the writing, art, and overall package are this good. This is grown folks’ comics, with the level of quality and cohesiveness that all comics should shoot for. You get invested, you pull the plot apart while the characters do, and in the end, your eyes bug out and your mouth gapes a little and you’re left fiending for the next volume.

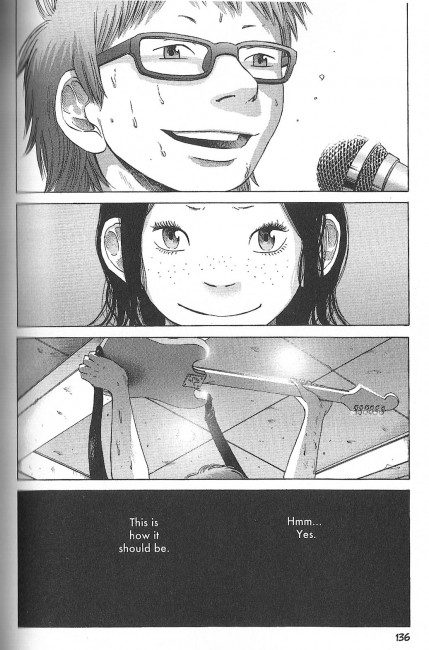

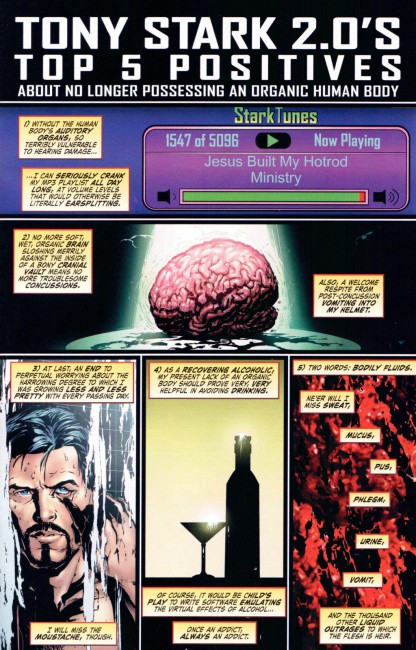

(My only suggestion, the only thing that could make BPRD a better comic, is to dedicate, say, four issues to the origin and day-to-day life of the mad scientist up there. He shows up a mere handful of times, but he’s got my complete attention every single time. He’s great.)

, above and beyond the glacial pacing and intricate web of relationships.